In the 1898 edition of The Swastika, Thomas Wilson cites two publications by Felix von Luschan regarding the swastika in Africa. I have never seen these old works referenced on the internet before, so in order to give visibility to them, I have republished them below in the original German and with an English translation.

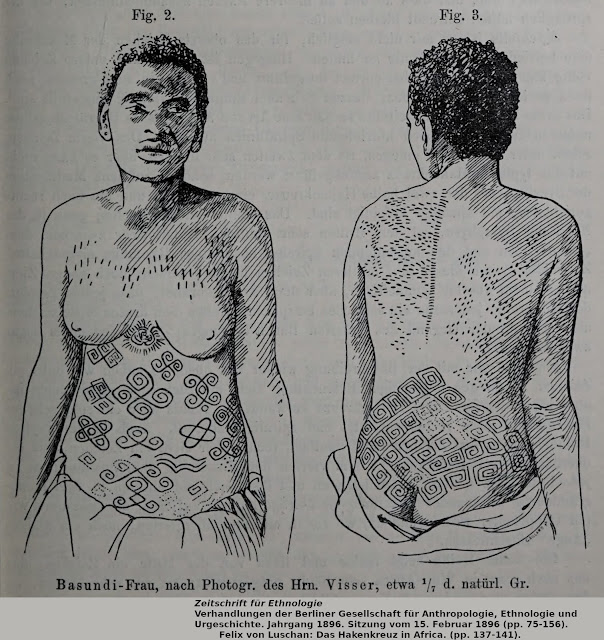

In the first of von Luschan's works published below, he examines some Akan goldweights and swastika-like spirals which form one of the motifs on scarification body art of a Basundi culture woman from the Congo. The woman was photographed by Robert Visser, and von Luschan includes a line-drawing illustration of the photo. (I wonder if this is perhaps the same culture that Alice Seeley Harris photographed? See: Swastikas in Africa, Congo).

In the second of von Luschan's works, there is an illustration of a carved gourd from the Yoruba culture with elaborate swastika-like patterns. Von Luschan credits British archaeologist Henry Balfour with bringing the artifact to his attention and sending an illustration of it.

Table of Contents:

-[Original German]. Felix von Luschan. (1896). Das Hakenkreuz in Africa.

-[English translation]. Felix von Luschan. (1896). The Swastika in Africa.

-[Original French]. Review of von Luschan's above article by Dr. Léon Laloy in the journal L'Anthropologie. (1896).

-[English translation]. Review of von Luschan's above article by Dr. Léon Laloy in the journal L'Anthropologie. (1896).

-Discussion of the Basundi ethnic group and "Kuilu/Kuili Basin" of Congo, which are a subject of the above paper.

-[Original German] Excerpt from: Felix von Luschan. (1897). Beitrage zur Volkerkunde der Deutschen Schutzgebiete.

-[English translation] Excerpt from: Felix von Luschan. (1897). Contributions to the Ethnology of the German Protectorates.

Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 1896. Berlin: A. Asher & Co.

Verhandlungen der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte. Jahrgang 1896.

Redigirt von Rudolf Virchow.

Sitzung vom 15. Februar 1896 (pp. 75-156).

(21) Hr. Felix von Luschan spricht über:

das Hakenkreuz in Africa. (pp. 137-141).

Article can be found here:

https://archive.org/details/zeitschriftfuret2818unse/page/136/mode/2up

Another link, which lists the citation for this somewhat confusingly-named publication.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23033655

Original German version:

Das Hakenkreuz, so häufig es uns in einigen europäischen und anderen Mittelmeer-Ländern, in Indien und in Ost-Asien begegnet, ist in anderen Welttheilen eine überaus seltene Erscheinung. Sein Vorkommen in America ist auf spärliche, vereinzelte Fälle von wenig typischer Form beschränkt, über die Brinton[1] berichtet hat, und aus Africa, soweit es nicht der Mittelmeer-Cultur angehört, kannte man bisher nur eine Reihe von Aschanti-Gewichten mit diesem Zeichen. Von diesen liegen mehrere im Britischen Museum; andere, aus englischem Privatbesitz, hat Schliemann[2] abgebildet.

Neuerdings hat das Berliner Museum f. Völkerkunde als Geschenk Dr. Gruner's von der Deutschen Togo-Expedition eine sehr grosse Anzahl von Aschanti-Gewichten erhalten, welche ich demnächst, zugleich mit unserem früheren, gleichfalls sehr reichen Bestände an solchen, veröffentlichen werde; ich lege einstweilen hier nur drei Stücke aus der Gruner'schen Reihe vor, von denen zwei das Hakenkreuz tragen; sie sind hier in natürlicher Grösse abgebildet. Wie alle anderen Aschanti-Gewichte, sind auch sie aus einem messingähnlichen Metalle gegossen und haben allerhand Gussfehler, von denen einer auch auf der Abbildung zur Geltung kommt; es ist indess nicht daran zu zweifeln, dass es sich da um wirkliche, typische Hakenkreuze handelt. Das eine ist nach rechts, das andere nach links gerichtet.

Gewichte der Aschanti, natürl. Grösse.

(Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.)

Das dritte der hier abgebildeten Stücke habe ich ausgewählt, weil völlig gleiche Spiralbildungen auch in Troja vielfach gefunden wurden[3], der Schliemann'sche Vergleich seiner trojanischen Hakenkreuze mit denen der Aschanti also auch auf diese Formen ausgedehnt werden könnte. Ich muss freilich sofort hinzufügen, dass völlig übereinstimmende Darstellungen auch sonst vielfach Vorkommen, selbst in Colombia,[4] wohin eine Uebertragung doch sicherlich völlig ausgeschlossen ist.

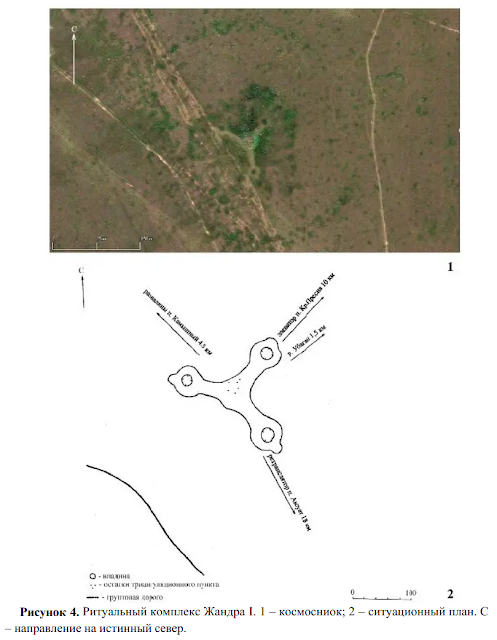

Fast zu gleicher Zeit mit diesen Aschanti-Gewichten erhielten wir durch Hrn. Robert Visser, dessen ganz besonderer Güte und Zuvorkommenheit sowohl das Königl. Museum f. Völkerkunde, als auch meine Lehrmittel-Sammlung schon viele werthvolle Zuwendungen verdanken, eine Reihe von Photographien und Notizen, die auf die Tättowirung im Flussgebiete des Kuilu Bezug haben. Darunter befanden sich auch mehrere Photographien einer Basundi-Frau, welche durch ihre besonders reiche Tättowirung schon Hrn. Visser aufgefallen war. Zwei dieser Photographien (Fig. 2 und 3) habe ich für die nebenstehende Abbildung umzeichnen lassen. Eine direkte Reproduction der Bilder durch Autotypie war leider durch technische Schwierigkeiten ausgeschlossen. Die Umzeichnung ist aber mit gewissenhafter Benutzung der Negative und unter meiner persönlichen Controle vorgenommen worden; auch wurde, was von den Narben nicht völlig deutlich war, nur mit punktirten Linien gezeichnet, so dass die Wiedergabe als eine durchaus zuverlässige und authentische gelten kann. Hierfür war es besonders günstig, dass von der Vorderseite zwei Aufnahmen Vorlagen, die bei verschiedener Beleuchtung gemacht waren und sich daher gegenseitig ergänzten.

Basundi-Frau, nach Photogr. des Hrn. Visser, etwa 1/7 d. natürl. Gr.

Technisch handelt es sich um die gewöhnliche, typische Narben-Tättowirung, aber die Darstellung selbst muss unser grösstes Interesse erregen, da sie eine ganze Reihe von Hakenkreuz-Motiven enthält. Nur in der Brustgegend und auf den oberen Rückenpartien sehen wir einfache Strich- und Dreieck-Muster, wie sie sonst so vielfach in West-Africa Vorkommen, hingegen ist die ganze vordere Bauchwand und die untere Rückenhälfte dicht mit Narben bedeckt, unter denen das Hakenkreuz und seine Ableitungen überwiegen. Die Darstellungen sind in der Hauptsache symmetrisch. Zunächst erkennt man in der Mittellinie fünf Zeichen, die genau über einander liegen; das oberste derselben ist mir leider unverständlich; es sieht so aus, als ob drei Blätter (oder Köpfe??) von einer unregelmässig rundlichen Linie eingeschlossen wären, von der aus nach allen Seiten dichtgestellte Linien radiär ausstrahlen. Es scheint auch, als ob die Narben an einigen Stellen anders verlaufen, als dies eigentlich beabsichtigt war. Es wäre das sicherlich nicht zu verwundern, da die Technik der Ziernarben ja eine sehr complicirte ist und selbst gerade Linien in der Regel nicht durch entsprechende Längsschnitte, sondern durch ein ganzes System zickzackartig verbundener kleiner, etwa senkrecht auf die Längsrichtung geführter Querschnitte hervorgebracht werden. Man wird leicht begreifen, dass bei solcher Technik die Herstellung von gekrümmten Ziernarben doppelt schwierig ist, und es ist ausserdem ganz leicht einzusehen, dass bei solchen Narben, besonders wenn sie auf kleinem Felde eine etwas dichtere Zeichnung wiedergeben sollen, die einzelnen Linien nicht immer so vernarben, wie das beabsichtigt war, und dass ab und zu mehrere Narben zusammenfliessen, die ursprünglich hätten getrennt bleiben sollen.

Jedenfalls ist es mir nicht möglich, für das oberste Zeichen der Mittelreihe eine befriedigende Erklärung zu finden. Hingegen ist das nächst untere Zeichen völlig klar; es ist wunderbar correct ausgeführt und enthält ein sehr grosses, nach links gerichtetes Hakenkreuz, dessen Schenkel sämmtlich spiralig eingerollt sind. Das dritte Zeichen der Mittelreihe enthält eine Art von Auge, dessen Begränzungslinie unten in zwei seitlich sich hinziehende Spirallinien ausläuft. Das vierte Zeichen, schon unter dem Nabel gelegen, ist dem zweiten sehr ähnlich, aber es kann nicht auf das typische Hakenkreuz zurückgeführt werden, sondern auf jene Modification der Svastika, bei der zwei halbe Hakenkreuze, ein nach links und ein nach rechts gerichtetes, mit einander vereinigt sind. Das fünfte Zeichen, schon ganz in der Nähe der Symphyse, ist dem dritten sehr ähnlich; es hat aber zwischen dem "Auge" oben und den auslaufenden Spiralen noch einen Rhombus eingeschaltet. Zu beiden Seiten dieser fünf mittleren Zeichen liegen jederseits noch andere Ziernarben, nicht absolut symmetrisch, aber doch so angeordnet, dass jedem Zeichen der Mittelreihe jederseits ein seitliches entspricht. Neben dem dritten Mittelzeichen, also etwa in der Gegend des grössten Bauch-Umfanges, liegen jederseits sogar zwei Zeichen.

Beginnen wir mit der Beschreibung wieder von oben, so haben wir links ein Zeichen, das wegen ungünstiger Beleuchtung nicht mit Sicherheit zu erkennen ist, aber jedenfalls auch dem Hakenkreuze verwandt ist, rechts aber ein sehr schönes Hakenkreuz, nach rechts gerichtet und spiralig eingerollt. Auch in der zweiten Reihe ist links das Zeichen nicht deutlich, rechts aber steht ein Zeichen, das bei oberflächlicher Betrachtung mit dem vierten der Mittelreihe übereinstimmt; es ist jedoch in ganz anderer Art entstanden und lässt sich am ehesten in zwei monogrammartig in einander verschlungene C-artige Figuren auflösen, die zusammen wie ein Doppeladler wirken und da, wo sie in einander übergreifen, noch ein kleines "Auge" einschliessen.

Die dritte Reihe zeigt rechts und links von der Mitte ein Zeichen, das uns auch sonst in West-Africa sehr häufig entgegentritt: ein aus sehr breiten, an den Enden abgerundeten Balken gebildetes, liegendes, schräges Kreuz; rechts ist es in seiner einfachsten Form vorhanden, links sind in alle fünf Felder nochi "Augen" eingezeichnet. Von den äusseren Zeichen dieser Reihe ist von dem) linken wogen der etwas seitlichen Drehung des Körpers und wegen der ganz ungünstigen Beleuchtung gar nichts mit Sicherheit zu erkennen; hingegen steht rechts wiederum ein wirkliches Hakenkreuz, genau gleich dem zweiten Zeichen der Mittelreihe, nach links gerichtet und mit spiralig eingedrehten Haken. In der vierten Reihe ist ein Zeichen besonders auffallend, es besteht aus drei über einander liegenden, fast horizontal verlaufenden Schlangenlinien.

Die Bedeutung all dieser Zeichen ist mir völlig unklar, aber ich verbinde mit der genauen Veröffentlichung derselben die Hoffnung, dass Hr. Visser und unsere anderen west-afrikanischen Gönner und Mitarbeiter vielleicht doch in die Lage kommen können, die einheimischen Namen und dann allmählich auch die wirkliche Bedeutung dieser Zeichen zu erfahren. Die wichtige Frage, ob derartige Zeichen übertragen sind oder selbständig entstehen konnten, würde durch solche Ermittelungen ihrer Lösung einen grossen Schritt näher rücken.

Einstweilen glaube ich persönlich an die Möglichkeit vollkommen selbständiger und unabhängiger Entstehung dieser Zeichen bei verschiedenen Völkern und zu verschiedenen Zeiten. Diejenigen, welche Uebertragung annehmen, müssen erst den Weg zeigen, auf dem eine solche erfolgt ist. Dass unsere Karten in fast unmittelbarer Nähe der Basundi, nur etwa 500 km von der Heimath der Frau entfernt, deren Hakenkreuz-Tättowirungen wir eben kennen gelernt haben (unter 10° östl. Länge und 2° südl. Breite), ein "Aschira-Land" verzeichnen, kann ich als einen solchen Nachweis nicht anerkennen. Wichtiger wäre es, darauf hin einmal genau die Bronze- und Kupfer-Gefässe zu untersuchen, die Flegel und andere Reisende aus den Haussa-Ländern gebracht haben. Diese sind in getriebener, gestanzter und gepunzter Arbeit reich verziert und haben sehr häufig Spiralen, Triquetra und andere Ornamente, welche wir sonst in Africa zu finden nicht gewohnt sind. —

[1] The ta-ki, the Svastika and the Cross in America; American philosophical Society 1888. Den da erwähnten Belegstücken wäre das Vorkommen verhältnissmässig recht typischer Hakenkreuze auf einem sehr schönen mexikanischen Steinjoch der Becker'sehen Sammlung anzureihen.

[2] Ilios, Leipzig 1881. S. 397.

[3] ebendas. S. 546-47.

[4] Vergl. Bastian in Zeitschrift der Berl. Ges. f. Erdkunde XIII, und R. Andree, Parallelen und Vergleiche 1878, S. 281, Taf III, Fig. 25.

English-language Google translate version:

Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 1896. Berlin: A. Asher & Co.

Proceedings of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory. Year 1896.

Edited by Rudolf Virchow.

Session of 15 February, 1896. (pp. 75-156).

(21) Mr. Felix von Luschan spoke about:

The Swastika in Africa. (pp. 137-141).

Article can be found here:

https://archive.org/details/zeitschriftfuret2818unse/page/136/mode/2up

Another link, which lists the citation for this somewhat confusingly-named publication.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23033655

The swastika, as often as we meet it in some European and other Mediterranean countries, in India and in East Asia, is an extremely rare occurrence in other parts of the world. Its occurrence in America is limited to sparse, isolated cases of a less typical form, about which Brinton[1] reported, and from Africa, as far as it does not belong to the Mediterranean culture, only a number of Ashanti weights have been known so far this sign. Several of these are in the British Museum; Schliemann[2] has reproduced others from private English ownership.

Recently the Berlin Museum of Ethnology as a gift from Dr. Gruner's have received a very large number of Ashanti weights from the German Togo Expedition, which I will publish shortly, at the same time as our earlier, also very rich inventory of such weights; For the time being I am only presenting three pieces from the Gruner series, two of which bear the swastika; they are shown here in their natural size. Like all other Ashanti weights, they are also cast from a brass-like metal and have all sorts of casting defects, one of which is shown to advantage in the illustration; there is, however, no doubt that these are real, typical swastikas. One is directed to the right, the other to the left.

Weights of the Ashanti, natural. Size.

(Museum of Ethnology, Berlin.)

I chose the third of the pieces shown here because completely identical spirals were also found in Troy many times,[3] so Schliemann's comparison of his Trojan swastikas with those of the Ashanti could also be extended to these shapes. Of course, I must immediately add that completely identical representations also occur in many other ways, even in Colombia,[4] where a transfer is certainly completely impossible.

Almost at the same time with these Ashanti weights we received from Mr. Robert Visser, whose very special kindness and courtesy both the Royal Museum of Ethnology, as well as my collection of teaching materials, owe many valuable donations, a number of photographs and notes relating to the tattooing in the Kuilu river basin. Among them were several photographs of a Basundi woman, who had already attracted Mr. Visser because of her particularly rich tattooing. I had two of these photographs (Figs. 2 and 3) redrawn for the illustration opposite. A direct reproduction of the pictures by autotype was unfortunately impossible due to technical difficulties. But the drawing was done with conscientious use of the negatives and under my personal control; also, what was not entirely clear from the scars, was only drawn with dotted lines, so that the reproduction can be regarded as a thoroughly reliable and authentic one. It was particularly beneficial for this to have two images from the front that were made with different lighting and therefore complemented each other.

Basundi woman, after a photograph from Mr. Visser, approximately 1/7th natural size.

Technically it is the usual, typical scar tattoo, but the representation itself must arouse our greatest interest, as it contains a whole series of swastika motifs. Only in the chest area and on the upper back we see simple line and triangle patterns, as they are found so often in West Africa, whereas the whole front abdominal wall and the lower half of the back are densely covered with scars, under which the swastika and its derivatives predominate. The representations are mainly symmetrical. First of all, you can see five characters in the center line that are exactly on top of each other; the topmost of these is unfortunately incomprehensible to me; it looks as if three leaves (or heads??) are enclosed by an irregularly rounded line from which lines densely packed radially radiate out on all sides. It also appears that the scars are in some places differently than intended. This would certainly not be surprising, since the technique of decorative scars is a very complex one and even straight lines are usually not produced by corresponding longitudinal cuts, but by a whole system of small, zigzag-like cross-sections, roughly perpendicular to the longitudinal direction. One will easily understand that with such a technique the production of curved decorative scars is doubly difficult, and it is also very easy to see that with such scars, especially if they are to reproduce a somewhat denser drawing on a small field, the individual lines are not always in this way scarred, as was intended, and that now and then several scars flow together that should originally have remained separate.

In any case, it is not possible for me to find a satisfactory explanation for the top character in the middle row. The next sign below, on the other hand, is perfectly clear; it is executed wonderfully correctly and contains a very large swastika pointing to the left, the legs of which are all rolled up spirally. The third character in the middle row contains a kind of eye, the boundary line of which ends in two laterally extending spiral lines. The fourth sign, already under the navel, is very similar to the second, but it cannot be traced back to the typical swastika, but to that modification of the Svastika, in which two half swastikas, one pointing to the left and one pointing to the right, with are united to one another. The fifth sign, already very close to the symphysis, is very similar to the third; but it has inserted a rhombus between the "eye" above and the terminating spirals. On both sides of these five central characters there are other decorative scars on each side, not absolutely symmetrical, but arranged in such a way that each character in the central row corresponds to one on each side. In addition to the third middle sign, i.e. in the area of the largest abdominal circumference, there are even two signs on each side.

If we start with the description again from above, we have a sign on the left that cannot be recognized with certainty due to poor lighting, but is in any case related to the swastika, but on the right a very beautiful swastika, directed to the right and curled in a spiral. In the second row, too, the sign is not clear on the left, but on the right there is a sign which, when viewed superficially, corresponds to the fourth in the middle row; However, it was created in a completely different way and can best be resolved into two monogram-like intertwined C-like figures, which together look like a double-headed eagle and, where they overlap, include a small "eye".

The third row shows, to the right and left of the center, a sign that we often encounter in other parts of West Africa: a lying, sloping cross made of very wide bars rounded at the ends; on the right it is in its simplest form, on the left there are still "eyes" drawn in all five fields. Of the outer signs of this series, nothing can be seen with certainty of the left billow, the somewhat lateral rotation of the body, and because of the very unfavorable lighting; on the other hand there is a real swastika on the right, exactly like the second symbol in the middle row, pointing to the left and with hooks twisted in a spiral. In the fourth row one sign is particularly noticeable, it consists of three on top of each other lying, almost horizontally running serpentine lines.

The meaning of all of these signs is completely unclear to me, but I associate the exact publication of the same with the hope that Mr. Visser and our other West African patrons and co-workers may after all be able to learn the local names and then gradually learn the real meaning of these symbols. The important question of whether such characters are transmitted or could arise independently would move a big step closer to their solution through such investigations.

In the meantime I personally believe in the possibility of completely independent and independent emergence of these signs among different peoples and at different times. Those who accept transmission must first show the way in which it has taken place. That our maps are in the immediate vicinity of the Basundi, only about 500 km from the home of the woman whose swastika tattoos we have just got to know (less than 10° east longitude and 2° south latitude), an "Aschira-Land" I cannot accept it as such evidence. It would be more important to examine the bronze and copper vessels that Flegel and other travelers brought from the Haussa countries. These are richly decorated in chased, punched and punched work and very often have spirals, triquetra and other ornaments that we are not used to find in Africa. -

[1] The ta-ki, the Svastika and the Cross in America; American philosophical Society 1888. The evidence mentioned there would include the occurrence of relatively typical swastikas on a very beautiful Mexican stone yoke in the Becker's collection.

[2] Ilios, Leipzig 1881. p. 397.

[3] Ibid., pp. 546-47.

[4] cf. Bastian in the Berl magazine. Ges. F. Geography XIII, and R. Andree, Parallels and Comparisons 1878, p. 281, Plate III, Fig. 25.

Review by Dr. Léon Laloy in L'Anthropologie, VII, No. 5, 1896, p. 606.

https://archive.org/details/lanthropologie7189unse/page/606/mode/2up

F. v. Luschan. Das Hakenkreuz in Africa (La croix gammée en Afrique). Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, XXVIII, fasc. 2, Berlin, 1896 (2 fig.).

On sait combien les croix gammées, si fréquentes en Europe et dans certaines parties de l'Asie, sont rares en Afrique. Pourtant ce signe se rencontre sur les poids des Aschantis. D'autre part, M. Luschan publie l'observation d'une femme Basundi, originaire du bassin du Kuili. Cette femme est couverte de tatouages par cicatrices, très compliqués et parmi lesquels dominent la croix gammée et ses dérivés. Les branches de la croix sont roulées en spirale, et dirigées soit à droite soit à gauche, On trouve également des demi-croix, des triangles, des signes ressemblant à deux lettres C entrelacées et d'autres dessins plus compliqués. Il nous a paru utile de signaler ce fait à l'attention des observateurs. Il serait intéressant de savoir si ces tatouages en croix gammées ne sont dus qu'au hasard, ou bien s'il s'agit là d'une coutume commune à une certaine race et ayant une signification traditionnelle.

- Dr. L. Laloy.

***

We know how rare are swastikas, so common in Europe and parts of Asia, in Africa. Yet this sign is found on the weights of the Aschantis. On the other hand, Mr. Luschan publishes the observation of a Basundi woman, from the Kuili basin. This woman is covered with tattoos by scars, very complicated and among which dominate the swastika and its derivatives. The branches of the cross are rolled in a spiral, and directed either to the right or to the left, There are also half-crosses, triangles, signs resembling two intertwined C letters and other more complicated designs. We thought it useful to bring this fact to the attention of observers. It would be interesting to know if these swastika tattoos were due to chance, or if it is a custom common to a certain race and having a traditional meaning.

- Dr. L. Laloy.

Discussion of the Basundi culture and the "Kuilu/Kuili basin".

On page 627 of the L'Anthropologie journal, it has a list of the titles of articles in the Verhandlungen der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte, 1896.

It says a French name for the culture is "Ba-Soundi":

F. von Luschan, Das Hakenkreuz in Africa (Le svastika en Afrique dans le tatouage des Ba-Soundi, sur les pieds des Achantis, etc.).

This culture is also referred to as "Basundi" (which von Luschan uses) and "Bassoundi".

For example, here is a postcard with an image taken by French photographer Jean-François Audema (1864-1921), labelled as "Congo Français. 107. - Type Bassoundi"

https://art.rmngp.fr/fr/library/artworks/jean-francois-audema_congo-francais-type-bassoundi

In this 2013 medical research article, the Basundi are listed as a tribe of the "Mayombian ethnic group". Mayombe is a geographic area near the mouth of the Congo river.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3808929/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayombe

Laloy describes the Basundi as being from the "Kuili basin" (von Luschan calls it the "Kuilu" basin).

There is a Kwilu (Quilo) river, a somewhat large river near the area where the Bassundi are noted to live on some old maps. The river is notable enough that a province is named after it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwilu_Province

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwilu_River

On this 1885 German map, the "Kuilu" is a large tributary of the Kwango river, in same same location as what is now called the Kwilu. It is possible Laloy was looking at a map and interpreted the font on the map to read "Kuili", I suppose. There is also a small river called "Kuilu" feeding directly into the Congo river as well. However, since he refers to the "Kuili basin" rather than mentioning the Congo river itself, it is probably not this small river.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~317147~90086027:Sektion-7--Congo

This 1901 map has its name as "Kuili". This being said, it seems the Kwilu/Kuilu/Kuili river is further east than maps typically show the Basundi ethnic group. Therefore, we may speculate the "Kuili basin" was not the precise location of where the individual was photographed.

https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~213570~5501054:Central-Africa-

The original photograph was taken by Robert Visser. I have not found an archive of his photos published online anywhere, but perhaps more information as to the precise location could be found.

Felix von Luschan. (1897). Beiträge zur Völkerkunde der deutschen Schutzgebiete. Erweiterte Sonderausgabe aus dem Amtlichen Bericht über die erste Deutsche Kolonial-Ausstellung in Treptow, 1896. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen).

Page 47. Book can be found here:

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_ey0-AAAAYAAJ/page/n53/mode/2up

Original German version:

Was hier nun zunächst für Togo in Betracht kommt, sind in erster Linie die Leute selbst, die von dort zur Ausstellung gesandt waren, dann die grosse Sammlung der Deutschen Togo-Expedition[1], die Sammlungen der Missionare und last not least die ausgezeichnete Sammlung, die Herr F. Schanker in Treptow/Rega ausgestellt hatte. Stammt die letztere zwar zum grössten Teile nicht aus dem deutschen Togo, sondern aus der unmittelbaren Nachbarschaft desselben, von der britischen Goldküste, so sind doch die wirklichen Beziehungen beider Gebiete so enge, dass eine wissenschaftliche Untersuchung des einen ohne Rücksichtnahme auf das andere ganz undenkbar wäre; die Schanker' sehe Sammlung bedeutete deshalb eine überaus erwünschte Ergänzung des aus Togo selbst ausgestellten Materials.

[...]

Ornamente einer Kürbisschale aus Yoruba. Abreibung von Henry Balfour.

Gleichfalls an östliche Beziehungen könnte das Vorkommen des Hakenkreuzes 卐 auf den Goldgewichten erinnern, welche wir der Togo-Expedition verdanken. Ich habe über diese bereits in den Verhandlungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft[2] berichtet und möchte im Anschluss daran hier nur eine westafrikanische Kürbisschale erwähnen, die wahrscheinlich aus Yoruba stammt und deren Kenntnis ich H. Balfour in Oxford verdanke. Das Original befindet sich gegenwärtig in dem dortigen Museum und lässt (vergl. die nebenstehenden Abbildungen) sehr deutlich erkennen, dass es sich wenigstens in diesem einen Falle um eine völlig selbständige, rein lokale Entwicklung handelt: Das Hakenkreuz ist diesmal nicht aus einem Storche,[3] sondern aus einer Eidechse hervorgegangen.

[1] Diese Expedition, deren Entsendung hauptsächlich Herrn Konsul Vohsen zu danken ist, stand unter Leitung Dr. Gruner's, dem sich Lieutenant von Carnap-Quernheimb und Dr. Döring angeschlossen hatten. Die ethnographischen Sammlungen derselben sind seither dureh Schenkung in den Besitz des Berliner Königl. Museums für Völkerkunde übergegangen, ebenso wie auch die Baseler Missions-Gesellschaft, die katholische Mission in Steyl und Herr Schänker einen wesentlichen Teil ihrer Sammlungen dem Königl. Museum geschenkt haben.

[2] Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 1896, Verh. S. 137 ff. [This is the same article posted in the first part of this web page.]

[3] Vergl.:

Karl von den Steinen. "Prähistorische Zeichen und Ornamente. Svastika. Triskeles. Runenalphabet." Festschrift für Adolf Bastian: zu seinem 70. Geburtstage, 26. Juni 1896. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. 1896. pp. 249-288.

https://archive.org/details/festschriftfurad00bast/page/248/mode/2up

Felix von Luschan. (1897). Contributions to the Ethnology of the German Protectorates. Enlarged special edition from the official report on the first German Colonial Exhibition in Treptow, 1896. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen).

Page 47. Book can be found here:

https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_ey0-AAAAYAAJ/page/n53/mode/2up

English-language Google translate version:

What comes first for Togo here are primarily the people themselves who were sent from there to the exhibition, then the large collection of the German Togo Expedition[1], the missionaries' collections and, last but not least, the excellent collection that Mr. F. Schanker had exhibited in Treptow/Rega. Although the latter does not originate for the most part from German Togo, but from its immediate vicinity, from the British Gold Coast, the real relationships between the two areas are so close that a scientific study of the one would be completely unthinkable without considering the other; The Schanker collection was therefore a very welcome addition to the material exhibited from Togo itself.

[...]

Ornaments on a gourd skin, from the Yoruba culture. Drawing by Henry Balfour.

The appearance of the swastika 卐 on the gold weights, which we owe to the Togo expedition, could also remind us of Eastern relations. I have already reported on this in the Proceedings of the Anthropological Society (Verhandlungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft)[2] and would like to mention only one West African gourd bowl, which probably comes from Yoruba and whose knowledge I owe to H. Balfour in Oxford. The original is currently in the local museum and shows (see the adjacent images) very clearly that at least in this one case it is a completely independent, purely local development: This time the swastika is not from a stork,[3] but emerged from a lizard.

[1] This expedition, the dispatch of which is mainly due to Consul Vohsen, was led by Dr. Gruner's, whom Lieutenant von Carnap-Quernheimb and Dr. Döring had joined. The ethnographic collections of the same have since been donated to the Berlin Königl. Museum für Völkerkunde, as well as the Baseler Missions-Gesellschaft, the Catholic Mission in Steyl and Mr. Schänker donated a substantial part of their collections to the Royal Museum.

[2] Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 1896, Verh. S. 137 ff. [This is the same article posted in the first part of this web page.]

[3] Compare with:

Karl von den Steinen. "Prähistorische Zeichen und Ornamente. Svastika. Triskeles. Runenalphabet." Festschrift für Adolf Bastian: zu seinem 70. Geburtstage, 26. Juni 1896. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. 1896. pp. 249-288.

https://archive.org/details/festschriftfurad00bast/page/248/mode/2up

Return to index of all swastika articles:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/the-swastika-aryan-symbol.html