Dr. Thomas Wilson (1832-1902) was Curator of the Department of Prehistoric Anthropology at the United States National Museum from 1887 presumably until his death in 1902. The US National Museum (today known as the National Museum of Natural History) is a branch of the Smithsonian Institution. Before this, Wilson served in the Union during the Civil War and as a US consul in Belgium and France.[1][2]

Trained in law, he was appointed chairman of a committee formed by the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1899.[3] The goal of this committee was to draft a law in order to preserve Native American archaeological artifacts located on federal lands. Up until this point, grave robbers private collectors had been able to take artifacts off of public lands. Beyond this, apparently the US government was unable to regulate foreign archaeologists from coming to the US and taking artifacts they had excavated back to their home nations, depleting the US of its historic heritage. After years of debate in Congress, the The Antiquities Act was passed in 1906.

Wilson's interest in the swastika seems to be his other defining contribution--his gravestone even has one carved into it.[4]

Ambitiously, Wilson attempted to catalog swastikas from across the world in his 1896 work The Swastika, the Earliest Known Symbol and published a map of his findings.[5] Wilson notes in the preface to his work that English-language works in the archaeology and history of the swastika were nearly non-existent.

While groundbreaking at the time, now 125 years old, his work is, of course, quite outdated. Nevertheless, simply reading Wilson's work would dispel many stupid notions which are still in common belief. For example, I have seen so many people say that because Buddhist swastikas are supposedly facing a different direction than "Nazi" swastikas, the swastika facing one direction is "good luck", while the "Nazi" swastika is also somehow distinct because it is rotated. In reality, swastikas facing both directions and rotated at different angles were in common use all over the globe, including among Buddhists.

(Compare this to how biological anthropologists writing during the 1890s had already established there was no such thing as a "white race", because of the tremendous history of admixture among the so-called "white race". Yet, our supposedly brilliant 21st century academics have forgotten.)

The purpose of this web page is to discuss information from Wilson's work and digitize it as the first step for making a 21st century digital version of his mapping attempt. Moreover, once and for all we will establish that the swastika is a world-wide and ancient symbol to which Neo-Nazis and other ethno-tribalist degenerates have no claim.

[1] Otis Mason. (1902). In Memoriam: Thomas Wilson. American Anthropologist, 4(2): 286-291.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/659223

[2] "Thomas Wilson." (1902). The Annals of Iowa, 5(6): 478-478.

https://doi.org/10.17077/0003-4827.2813

https://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?httpsredir=1&article=2813&context=annals-of-iowa

[3] Ronald F. Lee. (1970). The Antiquities Act of 1906. US Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/lee-story-antiquities.htm

[4] Find a Grave. Thomas Wilson (1832-1902).

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56626017/thomas-wilson

[5] Printed between page 904 and 905.

The full title of his work is:

Thomas Wilson. (1896). The Swastika, the Earliest Known Symbol, and its Migration; with Observations on the Migration of Certain Industries in Prehistoric Times. Report of the United States National Museum for 1894, pages 757-1011.

It can be accessed at the following links:

Screenshots of the figures were taken from the following version. For higher quality images of any figure, download and examine any one of the "single page" zip options.

https://archive.org/details/theswastika00wilsuoft/page/n7/mode/2up

(This version of the scan places the index (pages 759-761) at the very end for some reason).

https://archive.org/details/swastikaearlies00musegoog/page/n10/mode/2up

(Google Books scan with watermark on every page. Many of the figures are missing due to poor scan quality. Contains index at the beginning. Page numbering, etc. are the same.)

https://archive.org/details/cu31924023008067/page/n5/mode/2up

(Second(?) edition, published in 1898. Page numbering is the same. Contains additional appendix and index (pages 1013-1041). Pages 1013-1020 contain additional information and excerpts from letters that Wilson received after the initial publication).

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40812

(High quality digital reproduction of the first edition in HTML, EPUB, and Kindle format (including images) by Project Gutenberg).

For the sake of space, not all sections of this work have been reproduced below. For the sake of digital formatting, figures, etc. are not laid out precisely as they were in the printed work. Footnote numbering follows the numbers in the Project Gutenberg version.

For some further information on the history of this work's publication, see the appendix attached at the end of this web page.

The rest of this web page is excerpts from Wilson's book (essentially all the parts where he discusses artifacts with swastikas on them) with discussion and additional information about the artifacts cited by Wilson. I have not been able to find precise information on all the artifacts Wilson describes. If you have additional information and links to museums/collections where the artifacts are currently kept (including catalog number or other relevant archival information) or links to scientific publications describing the artifacts, please link them in the comments. No pseudo-archaeology or random links with unsubstantiated claims.

Keep in mind that many of the artifacts discussed by Wilson are not necessarily ancient and therefore do not give a perfect representation of the entire history of the swastika--it was already an ancient symbol belonging to time immemorial when these cultures made the artifacts! Countless new examples of swastikas have been discovered in the 125 years since Wilson made this work. And, of course, archaeological knowledge has advanced greatly since then, and dates or other information written in Wilson's work may no longer be accurate in light of new data.

Our goal is to carry the torch and one day include as many swastikas as possible on a digital map to demonstrate the world-wide distribution of this ancient symbol.

Click here to return to the index of swastika-related articles:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/the-swastika-aryan-symbol.html

- Preface

- I.--DEFINITION, DESCRIPTION, AND ORIGIN

- Different forms of the cross

- Names and definitions of the Swastika

- Symbolism and interpretation

- Origin and habitat

- II.--DISPERSION OF THE SWASTIKA

- Extreme Orient

- Classical Orient

- Africa

- Classical Occident--Mediterranean

- Europe

- United States of America

- Central America

- South America

- III.--FORMS ALLIED TO THE SWASTIKA

- Meanders, ogees, and spirals, bent to the left as well as to the right

- Aboriginal American engravings and paintings

- Designs on pottery

- IV.--THE CROSS AMONG THE AMERICAN INDIANS

- V.--SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SWASTIKA

- VI.--THE MIGRATION OF SYMBOLS

-

Babylonia, Assyria, Chaldea, and Persia

Phoenicia

Lycaonia

Armenia

Caucasus

Asia Minor--Troy (Hissarlik)

VII.--PREHISTORIC OBJECTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE SWASTIKA, FOUND IN BOTH HEMISPHERES, AND BELIEVED TO HAVE PASSED BY MIGRATIONS

VIII.--SIMILAR PREHISTORIC ARTS, INDUSTRIES, AND IMPLEMENTS IN EUROPE AND AMERICA AS EVIDENCE OF THE MIGRATION OF CULTURE

PREFACE

An English gentleman, versed in prehistoric archaeology, visited me in the summer of 1894, and during our conversation asked if we had the Swastika in America. I answered, "Yes," and showed him two or three specimens of it. He demanded if we had any literature on the subject. I cited him De Mortillet, De Morgan, and Zmigrodzki, and he said, "No, I mean English or American." I began a search which proved almost futile, as even the word Swastika did not appear in such works as Worcester's or Webster's dictionaries, the Encyclopedic Dictionary, the Encyclopedia Britannica, Johnson's Universal Cyclopedia, the People's Cyclopedia, nor Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, his Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, or his Classical Dictionary. I also searched, with the same results, Mollett's Dictionary of Art and Archeology, Fairholt's Dictionary of Terms in Art, "L'Art Gothique," by Gonza, Perrot and Chipiez's extensive histories of Art in Egypt, in Chaldea and Assyria, and in Phoenicia; also "The Cross, Ancient and Modern," by W. W. Blake, "The History of the Cross," by John Ashton; and a reprint of a Dutch work by Wildener. In the American Encyclopedia the description is erroneous, while all the Century Dictionary says is, "Same as fylfot," and "Compare Crux Ansata and Gammadion." I thereupon concluded that this would be a good subject for presentation to the Smithsonian Institution for "diffusion of knowledge among men."

[...]

Much of the information in this paper is original, and relates to prehistoric more than to modern times, and extends to nearly all the countries of the globe. It is evident that the author must depend on other discoverers; therefore, all books, travels, writers, and students have been laid under contribution without scruple. Due acknowledgment is hereby made for all quotations of text or figures wherever they occur.

Quotations have been freely made, instead of sifting the evidence and giving the substance. The justification is that there has never been any sufficient marshaling of the evidence on the subject, and that the former deductions have been inconclusive; therefore, quotations of authors are given in their own words, to the end that the philosophers who propose to deal with the origin, meaning, and cause of migration of the Swastika will have all the evidence before them.

Assumptions may appear as to antiquity, origin, and migration of the Swastika, but it is explained that many times these only reflect the opinion of the writers who are quoted, or are put forth as working hypotheses.

I.--DEFINITIONS, DESCRIPTION, AND ORIGIN

DIFFERENT FORMS OF THE CROSS

[...]

Of the many forms of the cross, the Swastika is the most ancient. Despite the speculations of students, its origin is unknown. It began before history...

[...]

... Prof. Max Müller makes the symbol different according as the arms are bent to the right or to the left. That bent to the right he denotes as the true Swastika, that bent to the left he calls Suavastika (fig. 10), but he gives no authority for the statement, and the author has been unable to find, expect in Burnouf, any justification for a different in names. Professor Goodyear gives the title of "Meander" to that form of Swastika which bends two or more times (fig. 11).

[...]

There are several varieties possibly related to the Swastika which have been found in almost every part of the globe, and though the relation may appear slight, and at first sight difficult to trace, yet it will appear more or less intimate as the examination is pursued through its ramifications. As this paper is an investigation into and report upon facts rather than conclusions to be drawn from them, it is deemed wise to give those forms bearing even possible relations to the Swastika. Certain of them have been accepted by the author as related to the Swastika, while others have been rejected; but this rejection has been confined to cases where the known facts seemed to justify another origin for the symbol. Speculation has been avoided.

NAMES AND DEFINITIONS OF THE SWASTIKA

[...]

... The definition and etymology of the word is thus given in Littre's French Dictionary:

Svastika, or Swastika, a mystic figure used by several (East) Indian sects. It was equally well known to the Brahmins as to the Buddhists. Most of the rock inscriptions in the Buddhist caverns in the west of India are preceded or followed by the holy (sacramentelle) sign of the Swastika. (Eug. Burnouf, "Le Lotus de la bonne loi." Paris, 1852, p. 625.) It was seen on the vases and pottery of Rhodes (Cyprus) and Etruria. (F. Delaunay, Jour. Off., Nov. 18, 1873, p. 7024, 3d Col.)

[...]

SYMBOLISM AND INTERPRETATION

[Aryan Anthropology author's note: In this section, Wilson quotes from dozens of authors who have speculated on the meaning, origin, and spread of the swastika. In summary, the different authors speculate all sorts of different meanings and origins, and nothing definitive can be said with the information archaeologists had amassed by the late 1800s. I have not yet personally read extensively of more modern investigations into the history and meaning of the swastika, but I doubt much more of a consensus has been reached.

Many authors believed it was a symbol of the sun, although Wilson disagrees that there is sufficient evidence of this. Whatever precise meaning it may have meant originally in the various different cultures which used it, in more recent times (such as in National Socialist iconography), it has frequently been envisioned as a sun symbol in art.]

Many theories have been presented concerning the symbolism of the Swastika, its relation to ancient deities and its representation of certain qualities. In the estimation of certain writers it has been respectively the emblem of Zeus, of Baal, of the sun, of the sun-god, of the sun chariot of Agni the fire-god, of Indra the rain-god, of the sky, the sky-god, and finally the deity of all deities, the great God, the Maker and Ruler of the Universe. It has also been held to symbolize light or the god of light, of the forked lightning, and of water. It is believed by some to have been the oldest Aryan symbol.

[...]

The Swastika sign had great extension and spread itself practically over the world, largely, if not entirely, in prehistoric times, though its use in some countries has continued into modern times.

The elaboration of the meanings of the Swastika indicated above and its dispersion or migrations form the subject of this paper.

Dr. Schliemann found many specimens of Swastika in his excavations at the site of ancient Troy on the hill of Hissarlik. They were mostly on spindle whorls, and will be described in due course. He appealed to Prof. Max Müller for an explanation, who, in reply, wrote an elaborate description, which Dr. Schliemann published in "Ilios."[10]

He commences with a protest against the word Swastika being applied generally to the sign Swastika, because it may prejudice the reader or the public in favor of its Indian origin. He says:

I do not like the use of the word svastika outside of India. It is a word of Indian origin and has its history and definite meaning in India. * * * The occurrence of such crosses in different parts of the world may or may not point to a common origin, hut if they are once called Svastika the vulgus profanum will at once jump to the conclusion that they all come from India, and it will take some time to weed out such prejudice.

Very little is known of Indian art before the third century B.C., the period when the Buddhist sovereigns began their public buildings.[11]

The name Svastika, however, can be traced (in India) a little farther back. It occurs as the name of a particular sign in the old grammar of Pânani, about a century earlier. Certain compounds are mentioned there in which the last word is karna, "ear." * * * One of the signs for marking cattle was the Svastika [fig. 41], and what Pânani teaches in his grammar is that when the compound is formed, svastika-karna, i.e., "having the ear marked with the sign of a Svastika," the final a of Svastika is not to be lengthened, while it is lengthened in other compounds, such as datra-karna, i.e., "having the ear marked with the sign of a sickle."

D'Alviella[12] reinforces Max Müller's statement that Panini lived during the middle of the fourth century, B.C. Thus it is shown that the word Swastika had been in use at that early period long enough to form an integral part of the Sanskrit language and that it was employed to illustrate the particular sounds of the letter a in its grammar.

Max Müller continues his explanation:[13]

It [the Swastika] occurs often at the beginning of the Buddhist inscriptions, on Buddhist coins, and in Buddhist manuscripts. Historically, the Svastika is first attested on a coin of Krananda, supposing Krananda to be the same king as Xandrames, the predecessor of Sandrokyptos, whose reign came to an end in 315 B.C. (See Thomas on the Identity of Xandrames and Krananda.) The paleographic evidence, however, seems rather against so early a date. In the footprints of Buddha the Buddhists recognize no less that sixty-five auspicious signs, the first of them being the Svastika [see fig. 32], (Eugene Burnouf, "Lotus de la bonne loi," p. 625); the fourth is the Suavastika, or that with the arms turned to the left [see fig. 10]; the third, the Nandyâvarta [see fig. 14], is a mere development of the Svastika. Among the Jainas the Svastika was the sign of their seventh Jina, Supârsva (Colebrooke "Miscellaneous Essays," II, p. 188; Indian Antiquary, vol. 2, p, 135).

In the later Sanskrit literature, Svastika retains the meaning of an auspicious mark; thus we see in the Râmâyana (ed. Gorresio, II, p. 348) that Bharata selects a ship marked with the sign of the Svastika. Varâhamihira in the Brihat-samhitâ (Med. Saec., vi, p. Ch.) mentions certain buildings called Svastika and Nandyâvarta (53.34, seq.), but their outline does not correspond very exactly with the form of the signs. Some Sthûpas, however, are said to have been built on the plan of the Svastika. * * * Originally, svastika may have been intended for no more than two lines crossing each other, or a cross. Thus we find it used in later times referring to a woman covering her breast with crossed arms (Bâlarâm, 75.16), svahastas-vastika-stani, and likewise with reference to persons sitting crosslegged.

Dr. Max Ohnefalsch-Richter[14] speaking of the Swastika position, either of crossed legs or arms, among the Hindus,[15] suggests as a possible explanation that those women bore the Swastikas upon their arms as did the goddess Aphrodite, in fig. 8 of his writings, (see fig. 180 in the present paper), and when they assumed the position of arms crossed over their breast, the Swastikas being brought into prominent view, possible gave the name to the position as being a representative of the sign.

Max Müller continues:[16]

Quite another question is, why the sign 卐 should have had an auspicious meaning, and why in Sanskrit it should have been called Svastika. The similarity between the group of letters sv in the ancient Indian alphabet and the sign of Svastika is not very striking, and seems purely accidental.

A remark of yours [Schliemann] (Troy, p. 38) that the Svastika resembles a wheel in motion, the direction of the motion being indicated by the crampons, contains a useful hint, which has been confirmed by some important observations of Mr. Thomas, the distinguished Oriental numismatist, who has called attention to the fact that in the long list of the recognized devices of the twenty-four Jaina Tirthankaras the sun is absent, but that while the eighth Tirthankara has the sign of the half-moon, the seventh Tirthankara is marked with the Svastika, i.e., the sun. Here, then, we have clear indications that the Svastika, with the hands pointing in the right direction, was originally a symbol of the sun, perhaps of the vernal sun as opposed to the autumnal sun, the Suavastika, and, therefore, a natural symbol of light, life, health, and wealth.

But, while from these indications we are justified in supposing that among the Aryan nations the Svastika may have been an old emblem of the sun, there are other indications to show that in other parts of the world the same or a similar emblem was used to indicate the earth. Mr. Beal * * * has shown * * * that the simple cross (+) occurs as a sign for earth in certain ideographic groups. It was probably intended to indicate the four quarters--north, south, east, west--or, it may be, more generally, extension in length and breadth.

That the cross is used as a sign for "four" in the Bactro-Pali inscriptions (Max Müller, "Chips from a German Workshop," Vol. ii, p. 298) is well known; but the fact that the same sign has the same power elsewhere, as, for instance, in the Hieratic numerals, does not prove by any means that the one figure was derived from the other. We forget too easily that what was possible in one place was possible also in other places; and the more we extend our researches, the more we shall learn that the chapter of accidents is larger than we imagine.

[...]

M. Eugene Burnouf[21] speaks of a third sign of the footprint of Çakya, called Nandâvartaya, a good augury, the meaning being the "circle of fortune," which is the Swastika inclosed within a square with avenues radiating from the corners (fig. 14). Burnouf says the above sign has many significations. It is a sacred temple or edifice, a species of labyrinth, a garden of diamonds, a chain, a golden waist or shoulder belt, and a conique with spires turning to the right.

Fig. 14.

Nandâvartaya, a third sign of the footprint of Buddha.

Burnouf, "Lotus de la Bonne Loi," Paris, 1852, p. 626.

[...]

Zmigrodzki, commenting on the frequency of the Swastika on the objects found by Dr. Schliemann at Hissarlik, gives it as his opinion[30] that these representations of the Swastika have relation to a human cult indicating a supreme being filled with goodness toward man. The sun, stars, etc., indicate him as a god of light. This, in connection with the idol of Venus, with its triangular shield engraved with a Swastika (fig. 125), and the growing trees and palms, with their increasing and multiplying branches and leaves, represent to him the idea of fecundity, multiplication, increase, and hence the god of life as well as of light. The Swastika sign on funeral vases indicates to him a belief in a divine spirit in man which lives after death, and hence he concludes that the people of Hissarlik, in the "Burnt City" (the third of Schliemann), adored a supreme being, the god of light and of life, and believed in the immortality of the soul.

R. P. Greg says:[31]

Originally it [the Swastika] would appear to hare been an early Aryan atmospheric device or symbol indicative of both rain and lightning, phenomena appertaining to the god Indra, subsequently or collaterally developing, possibly, into the Suastika, or sacred fire churn in India, and at a still later period in Greece, adopted rather as a solar symbol, or converted about B.C. 650 into the meander or key pattern.

[...]

Dr. H. Colley March, in his learned paper on the "Fylfot and the Futhore Tir,"[54] thinks the Swastika had no relation to fire or fire making or the fire god. His theory is that it symbolized axial motion and not merely gyration; that it represented the celestial pole, the axis of the heavens around which revolve the stars of the firmament. This appearance of rotation is most impressive in the constellation of the Great Bear. About four thousand years ago the apparent pivot of rotation was at α Draconis, much nearer the Great Bear than now, and at that time the rapid circular sweep must have been far more striking than at present. In addition to the name Ursa Major the Latins called this constellation Septentriones, "the seven plowing oxen," that dragged the stars around the pole, and the Greeks called it ἕλικη, from its vast spiral movement.[55] In the opinion of Dr. March all these are represented or symbolized by the Swastika.

Prof. W. H. Goodyear, of New York, has lately (1891) published an elaborate quarto work entitled "The Grammar of the Lotus: A New History of Classic Ornament as a Development of Sun Worship."[56] It comprises 408 pages, with 76 plates, and nearly a thousand figures. His theory develops the sun symbol from the lotus by a series of ingenious and complicated evolutions passing through the Ionic style of architecture, the volutes and spirals forming meanders or Greek frets, and from this to the Swastika. The result is attained by the following line of argument and illustrations:

The lotus was a "fetish of immemorial antiquity and has been worshiped in many countries from Japan to the Straits of Gibraltar;" it was a symbol of "fecundity," "life," "immortality," and of "resurrection," and has a mortuary significance and use. But its elementary and most important signification was as a solar symbol.[57]

He describes the Egyptian lotus and traces it through an innumerable number of specimens and with great variety of form. He mentions many of the sacred animals of Egypt and seeks to maintain their relationship by or through the lotus, not only with each other but with solar circles and the sun worship.[58] Direct association of the solar disk and lotus are, according to him, common on the monuments and on Phoenician and Assyrian seals; while the lotus and the sacred animals, as in cases cited of the goose representing Seb (solar god, and father of Osiris), also Osiris himself and Horus, the hawk and lotus, bull and lotus, the asp and lotus, the lion and lotus, the sphinx and lotus, the gryphon and lotus, the serpent and lotus, the ram and lotus--all of which animals, and with them the lotus, have, in his opinion, some related signification to the sun or some of his deities.[59] He is of the opinion that the lotus motif was the foundation of the Egyptian style of architecture, and that it appeared at an early date, say, the fourteenth century B.C. By intercommunication with the Greeks it formed the foundation of the Greek Ionic capital, which, he says,[60] "offers no dated example of the earlier time than the sixth century B.C." He supports this contention by authority, argument, and illustration.

He shows[61] the transfer of the lotus motif to Greece, and its use as an ornament on the painted vases and on those from Cyprus, Rhodes, and Melos (figs. 15, 16, 17).

Chantre[62] notes the presence of spirals similar to those of fig. 17, in the terramares of northern Italy and up and down the Danube, and his fig. 186 (fig. 17) he says represents the decorating motif, the most frequent in all that part of prehistoric Europe. He cites "Notes sur les torques on ornaments spirals."[63]

That the lotus had a foundation deep and wide in Egyptian mythology is not to be denied; that it was allied to and associated on the monuments and other objects with many sacred and mythologic characters in Egypt and afterwards in Greece is accepted. How far it extends in the direction contended for by Professor Goodyear, is no part of this investigation. It appears well established that in both countries it became highly conventionalized, and it is quite sufficient for the purpose of this argument that it became thus associated with the Swastika. Figs. 18 and 19 represent details of Cyprian vases and amphora belonging to the Cesnola collection in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, showing the lotus with curling sepals among which are interspersed Swastikas of different forms.

Fig. 18.

Detail of Cyprian vase showing lotuses with curling sepals.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Goodyear, "Grammar of the Lotus," pl. 47, fig. 1.

Fig. 19.

Detail of Cyprian amphora in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Lotus with curling sepals and different Swastikas.

Goodyear, "Grammar of the Lotus," pl. 47, figs. 2, 3.

Fig. 21.

Theory of lotus rudiments in spiral.

Tomb 33, Abd-el-Kourneh, Thebes.

Goodyear, "Grammar of the Lotus," p. 96.

Fig. 25.

Special Egyptian meander.

An illustration of the theory of derivation from the spiral.

Goodyear, "Grammar of the Lotus," pl. 10, fig. 9.

[...]

Professor Goodyear devotes an entire chapter to the Swastika. On pages 352, 353 he says:

There is no proposition in archaeology which can be so easily demonstrated as the assertion that the Swastika was originally a fragment of the Egyptian meander, provided Greek geometric vases are called in evidence. The connection between the meander and the Swastika has been long since suggested by Prof. A. S. Murray.[71] Hindu specialists have suggested that the Swastika produced the meander. Birdwood[72] says: "I believe the Swastika to be the origin of the key pattern ornament of Greek and Chinese decorative art." Zmigrodzki, in a recent publication,[73] has not only reproposed this derivation of the meander, but has oven connected the Mycenae spirals with this supposed development, and has proposed to change the name of the spiral ornament accordingly. * * * The equivalence of the Swastika with the meander pattern is suggested, in the first instance, by its appearance in the shape of the meander on the Rhodian (pl. 28, fig. 7), Melian (pl. 60, fig. 8), archaic Greek (pl. 60, fig. 9, and pl. 61, fig. 12), and Greek geometric vases (pl. 56). The appearance in shape of the meander may be verified in the British Museum on one geometric vase of the oldest type, and it also occurs in the Louvre.

On page 354, Goodyear says:

The solar significance of the Swastika is proven by the Hindu coins of the Jains. Its generative significance is proven by a leaden statuette from Troy. It is an equivalent of the lotus (pl. 37, figs. 1, 2, 3), of the solar diagram (pl. 57, fig. 12, and pl. 60, fig. 8), of the rosette (pl. 20, fig. 8), of concentric rings (pl. 47, fig. 11), of the spiral scroll (pl. 34, fig. 8, and pl.39, fig. 2), of the geometric boss (pl. 48, fig. 12), of the triangle (pl. 46, fig. 5), and of the anthemion (pl. 28, fig. 7, and pl. 30, fig. 4). It appears with the solar deer (pl. 60, figs. 1 and 2). with the solar antelope (pl. 37, fig. 9), with the symbolic fish (pl. 42, fig. 1), with the ibex (pl. 37, fig. 4), with the solar sphinx (pl. 34, fig. 8), with the solar lion (pl. 30, fig. 4), the solar ram (pl. 28, fig. 7), the solar horse (pl. 61, figs. 1, 4, 5, and 12). Its most emphatic and constant association is with the solar bird (pl. 60, fig. 15; fig. 173).

Count Goblet d'Alviella, following Ludwig Müller, Percy Gardner, S. Beal, Edward Thomas, Max Müller, H. Gaidoz, and other authors, accepts their theory that the Swastika was a symbolic representation of the sun or of a sun god, and argues it fully.[74] He starts with the proposition that most of the nations of the earth have represented the sun by a circle, although some of them, notably the Assyrians, Hindus, Greeks, and Celts, have represented it by signs more or less cruciform. Examining his fig. 2, wherein signs of the various people are set forth, it is to be remarked that there is no similarity or apparent relationship between the six symbols given, either with themselves or with the sun. Only one of them, that of Assyria, pretends to be a circle; and it may or may not stand for the sun. It has no exterior rays. All the rest are crosses of different kinds. Each of the six symbols is represented as being from a single nation of people. They are prehistoric or of high antiquity, and most of them appear to have no other evidence of their representation of the sun than is contained in the sign itself, so that the first objection is to the premises, to wit, that while his symbols may have sometimes represented the sun, it is far from certain that they are used constantly or steadily as such. ...

[...]

Fig. 27.

Detail of Greek geometric vase in the British Museum.

Swastika, right, with solar geese.

Goodyear, "Grammar of the Lotus," p. 353, fig. 173.

Fig. 28.

Greek geometric vase.

Swastika with solar geese.

Goodyear, "Grammar of the Lotus," p. 353, fig. 172.

[...]

Dr. Brinton[88] considers the Swastika as derived from the cross rather than from the circle, and the author agrees that this is probable, although it may be impossible of demonstration either way.

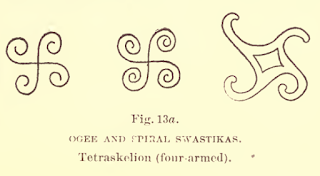

Several authors, among the rest d'Alviella, Greg, and Thomas, have announced the theory of the evolution of the Swastika, beginning with the triskelion, thence to the tetraskelion, and so to the Swastika. A slight examination is sufficient to overturn this hypothesis. In the first place, the triskelion, which is the foundation of this hypothesis, made its first appearance on the coins of Lycia. But this appearance was within what is called the first period of coinage, to wit, between 700 and 480 B.C., and it did not become settled until the second, and even the third period, 280 to 240 B.C., when it migrated to Sicily. But the Swastika had already appeared in Armenia, on the hill of Hissarlik, in the terramares of northern Italy, and on the hut-urns of southern Italy many hundred, possibly a thousand or more, years prior to that time. Count d'Alviella, in his plate 3 (see Chart I, p. 794), assigns it to a period of the fourteenth or thirteenth century B.C., with an unknown and indefinite past behind it. It is impossible that a symbol which first appeared in 480 B.C. could have been the ancestor of one which appeared in 1400 or 1300 B.C., nearly a thousand years before.

William Simpson[89] makes observations upon the latest discoveries regarding the Swastika and gives his conclusion:

* * * The finding of the Swastika in America gives a very wide geographical space that is included by the problem connected with it, but it is wider still, for the Swastika is found over the most of the habitable world, almost literally "from China to Peru," and it can be traced back to a very early period. The latest idea formed regarding the Swastika is that it may be a form of the old wheel symbolism and that it represents a solar movement, or perhaps, in a wider sense, the whole celestial movement of the stars. The Dharmachakra, or Buddhist wheel, of which the so-called "praying wheel" of the Lamas of Thibet is only a variant, can now be shown to have represented the solar motion. It did not originate with the Buddhists; they borrowed it from the Brahminical system to the Veda, where it is called "the wheel of the sun." I have lately collected a large amount of evidence on this subject, being engaged in writing upon it, and the numerous passages from the old Brahminical authorities leave no doubt in the matter. The late Mr. Edward Thomas * * * and Prof. Percy Gardner * * * declared that on some Andhra gold coins and one from Mesembria, Greece, the part of the word which means day, or when the sun shines, is represented by the Swastika. These details will be found in a letter published in the "Athenaeum" of August 20, 1892, written by Prof. Max Müller, who affirms that it "is decisive" of the symbol in Greece. This evidence may be "decisive" for India and Greece, but it does not make us quite certain about other parts of the world. Still it raises a strong presumption that its meaning is likely to be somewhat similar wherever the symbol is found.

It is now assumed that the Triskelion or Three Legs of the Isle of Man is only a variant of the Swastika. * * * There are many variants besides this in which the legs, or limbs, differ in number, and they may all be classed as whorls, and were possibly all, more or less, forms intended originally to express circular motion. As the subject is too extensive to be fully treated here, and many illustrations would be necessary, to those wishing for further details I would recommend a work just published entitled "The Migration of Symbols," by Count Goblet d'Alviella, with an introduction by Sir George Birdwood. The frontispiece of the book is a representation of Apollo, from a vase in the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, and on the middle of Apollo's breast there is a large and prominent Swastika. In this we have another instance going far to show its solar significance. While accepting these new interpretations of the symbol, I am still inclined to the notion that the Swastika may, at the same time, have been looked upon in some cases as a cross--that is, a pre-Christian cross, which now finds acceptance by some authorities as representing the four cardinal points. The importance of the cardinal points in primitive symbolism appears to me to have been very great, and has not as yet been fully realized. This is too large a matter to deal with here. All I can state is, that the wheel in India was connected with the title of a Chakravartin--from Chakra, a wheel--the title meaning a supreme ruler, or a universal monarch, who ruled the four quarters of the world, and on his coronation he had to drive his chariot, or wheel, to the four cardinal points to signify his conquest of them. Evidence of other ceremonies of the same kind in Europe can be produced. From instances such as these, I am inclined to assume that the Swastika, as a cross, represented the four quarters over which the solar power by its revolving motion carried its influence.

[10] Page 316, et seq.

[11] The native Buddhist monarchs ruled from about B.C. 500 to the conquest of Alexander, B.C. 330. See "The Swastika on ancient coins," Chapter II of this paper, and Waring, "Ceramic Art in Remote Ages," p. 83.

[12] "La Migration des symboles," p. 104.

[13] "Ilios," pp. 347, 348.

[14] Bulletins de la Société d'Anthropologie, 1888, p. 678

[15] Mr. Gandhi makes the same remark in his letter on the Buddha shell statue shown in pl. 10 of this paper.

[16] "Ilios," p. 348.

[21] "Lotus de la Bonne Loi," p. 626.

[30] Tenth Congress International d'Anthropologie et d'Archaeologie Prehistoriques, Paris, 1889, p. 474.

[31] Archaeologia, XLVII, pt. 1, p. 159.

[54] Trans. Lancaster and Cheshire Antiq. Soc., 1886.

[55] Haddon, "Evolution in Art," London, 1895, p 288.

[56] Sampson, Low, Marston & Co., London.

[57] Goodyear, "The Grammar of the Lotus," pp. 4, 5.

[58] Ibid., p. 6.

[59] Ibid., pp. 7, 8.

[60] Ibid., p. 71.

[61] Ibid., pp. 74, 77.

[62] "Age du Bronze," Deuxieme partie, p. 301.

[63] Matériaux pour l'Histoire Primitive et Naturelle de l'Homme, 3d ser. VIII, p. 6.

[71] Cesnola, "Cyprus, its Ancient Cities, Tombs, and Temples," p. 410.

[72] "Industrial Arts of India," p. 107.

[73] "Zur Geschichte der Swastika."

[74] "La Migration des Symboles," chap. 2, pt. 3, p. 66.

[88] Proc. Amer. Philosoph. Soc., 1889, XXIX, p. 180.

[89] Quarterly Statement of the Palestine Exploration Fund, January 1895, pp. 84, 85.

ORIGIN AND HABITAT

Prehistoric archaeologists have found in Europe many specimens of sculpture and engraving belonging to the Paleolithic age, but the cross is not known in any form, Swastika or other. In the Neolithic age, which spread itself over nearly the entire world, with many geometric forms of decoration, no form of the cross appears in times of high antiquity as a symbol or as indicating any other than an ornamental purpose. In the age of bronze, however, the Swastika appears, intentionally used, as a symbol as well as an ornament. Whether its first appearance was in the Orient, and its spread thence throughout prehistoric Europe, or whether the reverse was true, may not now be determined with certainty. It is believed by some to be involved in that other warmly disputed and much-discussed question as to the locality of origin and the mode and routes of dispersion of Aryan peoples. There is evidence to show that it belongs to an earlier epoch than this, and relates to the similar problem concerning the locality of origin and the mode and routes of the dispersion of bronze. Was bronze discovered in eastern Asia and was its migration westward through Europe, or was it discovered on the Mediterranean, and its spread thence? The Swastika spread through the same countries as did the bronze, and there is every reason to believe them to have proceeded contemporaneously--whether at their beginning or not, is undeterminable.

[...]

Professor Goodyear says:[1]

[...]

... In northern prehistoric Europe, where the Swastika has attracted considerable attention, it is distinctly connected with the bronze culture derived from the south. When found on prehistoric pottery of the north, the southern home of its beginnings is equally clear. ...

[...]

Dr. Brinton,[106] describing the normal Swastika, "with four arms of equal length, the hook usually pointing from left to right," says: "In this form it occurs in India and on very early (Neolithic) Grecian, Italic, and Iberian remains." Dr. Brinton is the only author who, writing at length or in a critical manner, attributes the Swastika to the Neolithic period in Europe, and in this, more than likely, he is correct. Professor Virchow's opinion as to the antiquity of the hill of Hissarlik, wherein Dr. Schliemann found so many Swastikas, should be considered in this connection. (see p. 832, 833 of this paper.) Of course, its appearance among the aborigines of America, we can imagine, must have been within the Neolithic period.

[100] "Grammar of the Lotus," p. 348 et seq.

[106] Proc. Amer. Philosoph. Soc., 1889, XXIX, p. 179

II.--DISPERSON OF THE SWASTIKA

EXTREME ORIENT

JAPAN

The Swastika was in use in Japan in ancient as well as modern times. Fig. 29 represents a bronze statue of Buddha, one-fifteenth natural size, from Japan, in the collection of M. Cernuschi, Paris. It has eight Swastikas on the pedestal, the ends all turned at right angles to the right. This specimen is shown by De Mortillet[107] because it relates to prehistoric man. The image or statue holds a cane in the form of a "tintin-nabulum," with movable rings arranged to make a jingling noise, and De Mortillet inserted it in his volume to show the likeness of this work in Japan with a number of similar objects found in the Swiss lake dwellings in the prehistoric age of bronze (p. 806).

The Swastika mark was employed by the Japanese on their porcelain. Sir Augustus W. Franks[108] shows one of these marks, a small Swastika turned to the left and in closed in a circle (fig. 30). Fig. 9 also represents a mark on Japanese bronzes.[109]

Fig. 29.

Bronze Statue of Buddha. Japan.

Eight Swasitkas on pedestal. Cane tintinnabulum with six movable rings or bells.

Additional information from the Appendix to the second edition (1898). (Page 1013).

S. D. Frey (Palatine Bridge, N.Y., April 27, 1897) encloses a mark on the side of an old Saki jar of Kioto ware, a swastika enclosed in a cross with four circles.

Miss E. R. Scidmore, the noted traveler and author, reports swastika marks in common use in Japan as decoration. She very politely presented the author with a set of small Japanese teacups with a comparatively large swastika in heavy lines, ends bent indiscriminately right and left, on the side of each.

In the Exposition de la musique au Palais d'industrie à Paris, 1896, was a series of thirty fine instruments, Japanese; "On one, a sort of guitar, 'biwa sacrée,' a swastika is sculptured." Reported by Dr. Delish, "L'Anthropologie," 1896, vol. VII, No. 6, p. 728.

[107] "Musée Préhistorique," fig. 1230; Bull. Soc. d'Anthrop., Paris., 1886, pp. 299, 313, 314.

[108] "Catalogue of Oriental Porcelain and Pottery," pl. 11, fig. 139.

[109] De Morgan, "Au Caucase," fig. 180.

KOREA

The U. S. National Museum has a ladies' sedan or carrying chair from Korea. It bears eight Swastika marks, cut by stencil in the brass-bound corners, two on each corner, one looking each way. The Swastika is normal, with arms crossing at right angles, the ends bent at right angles and to the right. It is quite plain; the lines are all straight, heavy, of equal thickness, and the angles all at 90 degrees. In appearance it resembles the Swastika in fig. 9.

CHINA

In the Chinese language the sign of the Swastika is pronounced wan (p. 801), and stands for "many," "a great number," "ten thousand," "infinity," and by a synecdoche is constructed to mean "long life, a multitude of blessings, great happiness," etc.; as is said in French, "mille pardons," "mille remercîments," a thousand thanks, etc. During a visit to the Chinese legation in the city of Washington, while this paper was in progress, the author met one of the attachés, Mr. Chung, dressed in his robes of state; his outer garment was of moiré silk. The pattern woven in the fabric consisted of a large circle with certain marks therein, prominent among which were two Swastikas, one turned to the right, the other to the left. The name given to the sign was reported above, wan, and the significance was "longevity," "long life," "many years." Thus was shown that in far as well as near countries, in modern as well as ancient times, this sign stood for blessing, good wishes, and, by a slight extension, for good luck.

The author conferred with the Chinese minister, Yang Yu, with the request that he should furnish any appropriate information concerning the Swastika in China. In due course the author recieved the following letter and accompanying notes with drawings:

* * * I have the pleasure to submit abstracts from historical and literary works on the origin of the Swastika in China and the circumstances connected with it in Chinese ancient history. I have had this paper translated into English and illustrated by india-ink drawings. The Chinese copy is made by Mr. Ho Yen-Shing, the first secretary of the legation, translation by Mr. Chung, and drawings by Mr. Li.

With assurance of my high esteem, I am,

Very cordially, Yang Yu.Buddhist philosophers consider simple characters as half or incomplete characters and compound characters as complete characters, while the Swastika 卍 is regarded as a natural formation. A Buddhist priest of the Tang Dynasty, Tao Shih by name, in a chapter of his work entitled Fa Yuen Chu Lin, on the original Buddha, describes him as having this 卍 mark oh his breast and sitting on a high lily of innumerable petals. [Pl. 1.]

Plate 1. Origin of Buddha According to Tao Shih, with Swastika Sign.

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

Empress Wu (684-704 A.D.), of the Tang Dynasty, invented a number of new forms for characters already in existence, amongst which [left-facing swastika in a circle] was the word for sun, [Z in a circle] for moon, [circle] for star, and so on. These characters were once very extensively used in ornamental writing, and even now the word [left-facing swastika in a circle] sun may be found in many of the famous stone inscriptions of that age, which have been preserved to us up to the present day. [Pl. 2.]

Plate 2. Swastika Decreed by Emperess Wu (684-704 A.D.) as a Sign for Sun in China.

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

The history of the Tang Dynasty (620-906 A.D.), by Lui Hsu and others of the Tsin Dynasty, records a decree issued by Emperor Tai Tsung (763-779 A.D.) forbidding the use of the Swastika on silk fabrics manufactured for any purpose. [Pl. 3.]

Plate 3. Swastika Design on Silk Fabrics.

This use of the swastika was forbidden in China by Emperor Tai Tsung (763-779 A.D.)

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

Fung Tse, of the Tang Dynasty, records a practice among the people of Loh-yang to endeavor, on the 7th of the 7th month of each year, to obtain spiders to weave the Swastika on their web. Kung Ping-Chung, of the Sung Dynasty, says that the people of Loh-yang believe it to be good luck to find the Swastika woven by spiders over fruits or melons. [Pl. 4.]

Plate 4. Swastika in Spider Web over Fruit.

(A good omen in China.)

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

Sung Pai, of the Sung Dynasty, records an offering made to the Emperor by Li Yuen-su, a high official of the Tang Dynasty, of a buffalo with a Swastika on the forehead, in return for which offering he was given a horse by the Emperor. [Pl. 5.]

Plate 5. Buffalo with Swastika on Forehead.

Presented to Emperor of Sung Dynasty.

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

The Ts'ing-I-Luh, by Tao Kuh, of the Sung Dynasty, records that an Empress in the time of the South Tang Dynasty had an incense burner the external decoration of which had the Swastika design on it. [Pl. 6.]

Plate 6. Incense Burner with Swastika Decoration.

South Tang Dynasty.

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

Chu I-Tsu, in his work entitled Ming Shih Tsung, says Wu Tsung-Chih, a learned man of Sin Shui, built a residence outside of the north gate of that town, which he named "Wan-Chai," from the Swastika decoration of the railings about the exterior of the house. [Pl. 7.]

Plate 7. House of Wu Tsung-Chih of Sin Shui, with Swastika in Railing.

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

An anonymous work, entitled the Tung Hsi Yang K'ao, described a fruit called shan-tsao-tse (mountain or wild date), whose leaves resemble those of the plum. The seed resembles the lichee, and the fruit, which ripens in the ninth month of the year, suggests a resemblance to the Swastika. [Pl. 8.]

Plate 8. Mountain or Wild Date.--Fruit Resembling the Swastika.

From a drawing by Mr. Li, presented to the U.S. National Museum by Mr. Yang Yü, Chinese Minister, Washington, D.C.

The Swastika is one of the symbolic marks of the Chinese porcelain. Prime[110] shows what he calls a "tablet of honor," which represents a Swastika inclosed in a lozenge with loops at the corners (fig. 31). This mark on a piece of porcelain signifies that it is an imperial gift.

Fig. 31.

Potter's mark on porcelain. China.

Tablet of honor, with Swastika.

Prime, "Pottery and Porcelain," p. 254.

Major-General Grordon, controller of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, England, writes to Dr. Schliemann:[111] "The Swastika is Chinese. On the breech chasing of a large gun lying outside my office, captured in the Taku fort, you will find this same sign." But Dumoutier[112] says this sign is nothing else than the ancient Chinese character che, which, according to D'Alviella,[113] carries the idea of perfection or excellence, and signifies the renewal and perpetuity of life. And again,[111] "Dr. Lockyear, formerly medical missionary to China, says the sign 卍 is thoroughly Chinese."

The Swastika is found on Chinese musical instruments. The U.S. National Museum possesses a Hu-Ch'in, a violin with four strings, the body of which is a section of bamboo about 3.5 inches in diameter. The septum of the joint has been cut away so as to leave a Swastika of normal form, the four arms of which are connected with the outer walls of the bamboo. Another, a Ti-Ch'in, a two-stringed violin, with a body of cocoanut, has a carving which is believed to have been a Swastika; but the central part has been broken out, so that the actual form is undetermined.

Prof. George Frederick Wright, in an article entitled "Swastika,"[114] quotes Rev. F. H. Chalfont, missionary at Chanting, China, as saying: "Same symbol in Chinese characters 'ouan,' or 'wan,' and is a favorite ornament with the Chinese."

Additional information from the Appendix to the second edition (1898). (Page 1014).

Mr. R. E. Martyr (letter of January 20, 1898) notifies of the occurrence of variations of the swastika occurring in Solo, a dialect of western Ssu-ch'uan, citing Baber's Travels in 1881; also a Journey in that country, by Mr. F. S. A. Bourne, Parliamentary Papers C. 5371/88, China No. 1, 1888.

* Blogger's note: In the Appendix this is labelled under the section "Java", but Ssu-ch'uan is an old spelling of the Chinese province of Sichuan.

https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Ssu-ch%27uan

Edward Colborne Baber was a British man who was employed as a diplomat in China, and he travelled extensively within China in the 1870s and 1880s. He published a number of works about his travels and died in 1890.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Colborne_Baber

https://worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n85-207688/

Frederick Samuel Augustus Bourne was a British judge and diplomat serving in China from 1876 to 1916.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Samuel_Augustus_Bourne

I did not try to find the report in the Parliamentary Papers, but here is another citation for Bourne's report:

Bourne, F. S., "Report of a journey in southwestern China," China #1, 1888 (C. 5371).

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-asian-studies/article/yunnan-myth/464EF7E0E2BB6D482FE44563366E90B8

I couldn't find any information on the "Solo dialect" in Sichuan. However, "Solo" is the colloquial name for the city of Surakarta, a large city on the island of Java. It was the capital of the powerful Surakarta Sunanate (sometimes called the Principality of Solo). Wilson probably hastily looked up Solo in an encyclopedia, leading to an erroneous association with Java?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sichuanese_dialects

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surakarta

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surakarta_Sunanate

[110] "Pottery and Porcelain," p. 254.

[111] "Ilios," p. 352.

[112] "Le Swastika et la roue solaire en Chine," Revue d'Ethnographie, IV, pp. 319, 350.

[113] "La Migration des Symboles," p. 55.

[114] New York Independent, November 16, 1893; Science, March 23, 1894, p. 162.

TIBET

Mr. William Woodville Rockhill,[115] speaking of the fair at Kumbum, says:

I found there a number of Lh'asa Tibetans (they call them Gopa here) selling pulo, beads of various colors, saffron, medicines, peacock feathers, incense sticks, etc. I had a talk with these traders, several of whom I had met here before in 1889. * * * One of them had a Swastika (yung-drung) tattooed on his hand, and I learned from this man that this is not an uncommon mode of ornamentation in his country.

Count D'Alviella says that the Swastika is continued among the Buddhists of Tibet; that the women ornament their petticoats with it, and that it is also placed upon the breasts of their dead.[116]

He also reports[117] a Buddhist statue at the Musée Guimet with Swastikas about the base. He does not state to what country it belongs, so the author has no means of determining if it is the same statue as is represented in fig. 29.

Additional information from the Appendix to the second edition (1898). (Page 1013).

Hon. W. W. Rockhill (Department of State, December 26, 1896) calls

Your [my] attention to the existence in Tibet of a religion, the name of which translated means "The Religion of the Swastika," and in which this sign plays a most important role. This religion, which is also known as the Bon Religion, is probably the modern form of the Pre-Buddhist Shaminism of Tibet. It has a voluminous literature, some few works of which have been translated into European languages, in which you will find many interesting references to this sign. Chinese works also contain numerous references and explanations of its meaning and origin.

[115] "Diary of a Journey through Mongolia and Tibet in 1891-92," p. 67.

[116] "La Migration des Symboles," p. 55, citing note 1, Journ. Asiatique, 2nd série, IV, p. 245, and Palla, "Sammlungen historischer Naehriehten über die mongolischen Völkerschaften," I, p. 277.

[117] Ibid., p. 55.

INDIA

Burnouf[118] says approvingly of the Swastika:

Christian archaeologists believe this "was the most ancient sign of the cross. * * * It was used among the Brahmins from all antiquity. (Voyez mot "Swastika" dans notre dictionnaire Sanskrit.) Swastika, or Swasta, in India corresponds to "benediction" among Christians.

Fig. 32.

Footprint of Buddha with Swastika, from Amaravati tope.

From a figure by Fergusson and Schliemann.

The same author, in his translation of the "Lotus de la Bonne Loi," one of the nine Dharmas or Canonical books of the Buddhists of the North, of 280 pages, adds an appendix of his own writing of 583 pages; and in one (No. 8) devoted to an enumeration and description of the sixty-five figures traced on the footprint of Çakya (fig. 32) commences as follows:

1. Svastikaya: This is the familiar mystic figure of many Indian sects, represented thus, 卐, and whose name signifies, literally, "sign of benediction or of good augury." (Rgya tch'er rol pa, Vol. 11, p. 110).

* * * The sign of the Swastika was not less known to the Brahmins than to the Buddhists. "Ramayana," Vol. II, p. 348, ed. Gor., Chap. XCVII, st. 17, tells of vessels on the sea bearing this sign of fortune. This mark, of which the name and usage are certainly ancient, because it is found on the oldest Buddhist medals, may have been used as frequently among the Brahmins as among the Buddhists. Most of the inscriptions on the Buddhist caverns in western India are either preceded or followed by the holy (sacramentelle) sign of the Swastika. It appears less common on the Brahmin monuments.

Mr. W. Crooke (Bengal Civil Service, director of Eth. Survey, Northwest Provinces and Oudh), says:[119]

The mystical emblem of the Swastika, which appears to represent the sun in his journey through the heavens, is of constant occurrence. The trader paints it on the flyleaf of his ledger, he who has young children or animals liable to the evil eye makes a representation of it on the wall beside his doorpost. It holds first place among the lucky marks of the Jainas. It is drawn on the shaven heads of children on the marriage day In Gujarat. A red circle with Swastika in the center is depicted on the place where the family gods are kept (Campbell, Notes, p. 70). In the Meerut division the worshiper of the village god Bhumiya constructs a rude model of it in the shrine by fixing up two crossed straws with a daub of plaster. It often occurs in folklore. In the drama of the Toy Cart the thief hesitates whether he shall make a hole in the wall of Charudatta's house in the form of a Swastika or of a water jar (Manning, Ancient India, 11, 160).

Village shrines.--The outside (of the shrines) is often covered with rude representations of the mystical Swastika.

On page 250 he continues thus:

Charms.--The bazar merchant writes the words "Ram Ram" over his door, or makes an image of Genesa, the god of luck, or draws the mystical Swastika. The jand tree is reverenced as sacred by Khattris and Brahmins to avoid the evil eye in children. The child is brought at 3 years of age before a jand tree; a bough is cut with a sickle and planted at the foot of the tree. A Swastika symbol is made before it with the rice flour and sugar brought as an offering to the tree. Threads of string, used by women to tie up their hair, are cut in lengths and some deposited on the Swastika.

Mr. Virchand E. Gandhi, a Hindu and Jain disciple from Bombay, India, a delegate to the World's Parliament of Religions at Chicago in 1893, remained for sometime in Washington, D.C., proselyting among the Christians. He is a cultivated gentleman, devoted to the spread of his religion. I asked his advice and assistance, which he kindly gave, supervising my manuscript for the Swastika in the extreme Orient, and furnishing me the following additional information relative to the Swastika in India, and especially among the Jains:

The Swastika is misinterpreted by so-called Western expounders of our ancient Jain philosophy. The original idea was very high, but later on some persons thought the cross represented only the combination of the male and the female principles. While we are on the physical plane and our propensities on the material line, we think it necessary to unite these (sexual) principles for our spiritual growth. On the higher plane the soul is sexless, and those who wish to rise higher than the physical plane must eliminate the idea of sex.

I explain the Jain Swastika by the following illustration [fig. 33]: The horizontal and vertical lines crossing each other at right angles form the Greek cross. They represent spirit and matter. We add four other lines by bending to the right each arm of the cross, then three circles and the crescent, and a circle within the crescent. The idea thus symbolized is that there are four grades of existence of souls in the material universe. The first is the lowest state--Archaic or protoplasmic life. The soul evolves from that state to the next--the earth with its plant and animal life. Then follows the third stage--the human; then the fourth stage--the celestial. The word--"celestial" is here held to mean life in other worlds than our own. All these graduations are combinations of matter and soul on different scales. The spiritual plane is that in which the soul is entirely freed from the bonds of matter. In order to reach that plane, one must strive to possess the three jewels (represented by the three circles), right belief, right knowledge, right conduct. When a person has these, he will certainly go higher until he reaches the state of liberation, which is represented by the crescent. The crescent has the form of the rising moon and is always growing larger. The circle in the crescent represents the omniscient state of the soul when it has attained full consciousness, is liberated, and lives apart from matter.

The interpretation, according to the Jain view of the cross, has nothing to do with the combination of the male and female principle. Worship of the male and female principles, ideas based upon sex, lowest even of the emotional plane, can never rise higher than the male and female.

The Jains make the Swastika sign when we enter our temple of worship. This sign reminds us of the great principles represented by the three jewels and by which we are to reach the ultimate good. Those symbols intensify our thoughts and make them more permanent.

Fig. 33.

Explanation of the Jain Swastika, according to Gandhi.

(1) Archaic or protoplasmic life; (2) Plant and animal life; (3) Human life; (4) Celestial life.

Fig. 34a.

The formation of the Jain Swastika--first stage.

Handful of rice or meal, in circular form, thinner in center.

Fig. 34b.

The formation of the Jain Swastika--second stage.

Rice or meal, as shown in the preceding figure, with finger marks, indicated at 1, 2, 3, 4.

Mr. Gandhi says the Jains make the sign of the Swastika as frequently and deftly as the Roman Catholics make the sign of the cross. It is not confined to the temple nor to the priests or monks. Whenever or wherever a benediction or blessing is given, the Swastika is used. Figs. 34 a, b, c form a series showing how it is made. A handful of rice, meal, flour, sugar, salt, or any similar substance, is spread over a circular space, say, 3 inches in diameter and one-eighth of an inch deep (fig. 34a), then commence at the outside of the circle (fig. 34b), on its upper or farther left-hand corner, and draw the finger through the meal just to the left of the center, halfway or more to the opposite or near edge of the circle (1), then again to the right (2), then upward (3), finally to the left where it joins with the first mark (4). The ends are swept outward, the dots and crescent put in above, and the sign is complete (fig. 34c).

Fig. 34c.

The formation of the Jain Swastika--third stage.

Ends turned out, typifying animal, human, and celestial life, as shown in fig. 33.

The sign of the Swastika is reported in great numbers, by hundreds if not by thousands, in the inscriptions on the rock walls of the Buddhist caves in India. It is needless to copy them, but is enough to say that they are the same size as the letters forming the inscription; that they all have four arms and the ends turn at right angles, or nearly, so, indifferently to the right or to the left. The following list of inscriptions, containing the Swastikas, is taken from the first book coming to hand--the "Report of Dr. James Burgess on the Buddhist Cave Temples and their Inscriptions, Being a Part of the Result of the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Seasons' Operations of the Archaeological Survey of Western India, 1876, 1877, 1878, 1879:"[120]

Chantre[121] says:

I remind you that the (East) Indians, Chinese, and Japanese employ the Swastika, not only as a religious emblem but as a simple ornament in painting on pottery and elsewhere, the same as we employ the Greek fret, lozenges, and similar motifs in our ornamentation. Sistres [the staff with jingling bells, held in the hand of Buddha, on whose base is engraved a row of Swastikas, fig. 29 of present paper] of similar form and style have been found in prehistoric Swiss lake dwellings of the bronze age. Thus the sistres and the Swastika are brought into relation with each other. The sistres possibly relate to an ancient religion, as they did in the Orient; the Swastika may have had a similar distinction.

De Mortillet and others hold the same opinion.[122]

Additional information from the Appendix to the second edition (1898). (Page 1013-1014).

General Lew Wallace, "Prince of India," vol. I, p. 263:

"I am a Prince of India. * * * I began walk as a priest--a disciple of Siddartha--whom my Lord, of his great intelligence, will remember was born in Central India. Very early, on account of my skill in translating, I was called to China and there put to rendering the thirty-five discourses of the father of the Buddhisottwa into Chinese and Thibettan. I also published a version of the Lotus of the Good Law, and another of the Nirvâna. These brought me great honor. To an ancestor of mine, Maha Kashiapa, Buddha happened to have intrusted his innermost mysteries--that is, he made him Keeper of the Pure Secret of the Eye of Right Doctrine. Behold the symbol of that doctrine."

The Prince drew a leaf of ivory, worn and yellow, from a pocket under his pelisse and passed it to Mahommed, saying, "Will my lord look?"

Mahommed took the leaf, and in the silver sunk into it saw this sign:

[left-facing swastika, rotated 45 degrees]

"I see," he said, gravely. "Give me its meaning."

"Nay, my Lord, did I that, the doctrine of which, as successor of Kashiapa, though far removed, they made me Keeper--the very highest of Buddhistic honors--would then be no longer a secret. The symbol is of vast sanctity. There is never a genuine image of Buddha without it over his heart. It is the monogram of Vishnu and Siva, but as to its meaning I can only say every Brahmin of learning views it worshipfully, knowing it the compression of the whole mind of Buddha."

[118] "Des Sciences et Religion," p. 256.

[119] "Introduction to popular Religion and Folk Lore of Northern India," p. 58.

[120] Trubner & Co., London, 1883, pp. 140. pl. 60.

[121] "Âge du Bronze," pt. 1, p. 206.

[122] "Musée Préhistorique," pl. 98; "Notes de l'Origine Orientale de la Métallurgie," Lyon, 1879; "L'Âge de la Pierre et du Bronze dans l'Asie Occidentale," Bull. Soc. d'Anthrop., Lyon, I, fasc. 2, 1882; Bull. Soc. d'Anthrop de Paris, 1886, pp. 299, 313, and 314.

CLASSICAL ORIENT

BABYLONIA, ASSYRIA, CHALDEA, AND PERSIA

Waring[123] says, "In Babylonian and Assyrian remains we search for it [the Swastika] in vain." Max Müller and Count Goblet d'Alviella are of the same opinion.[124]

Of Persia, D'Alviella (p. 51), citing Ludwig Müller,[125] says that the Swastika is manifested only by its presence on certain coins of the Arsacides and the Sassanides.

PHOENICIA

It is reported by various authors that the Swastika has never been found in Phoenicia, e.g. Max Müller, J. B. Waring, Count Goblet d'Alviella.[126]

Ohnefalsch-Richter[127] says that the Swastika is not found in Phoenicia, yet he is of the opinion that their emigrant and commercial travelers brought it from the far east and introduced it into Cyprus, Carthage, and the north of Africa. (see p. 796).

LYCAONIA

Lempriere, in his Classical Dictionary, under the above title, gives the following:

A district of Asia Minor forming the southwestern quarter of Phrygia. The origin of its name and inhabitants, the Lycaones, is lost in obscurity. * * * Our first acquaintance with this region is in the relation of the expedition of the younger Cyprus. Its limits varied at different times. At first it extended eastward from Iconium 23 geographical miles, and was separated from Cilicia on the south by the range of Mount Taurus, comprehending a large portion of what in later times was termed Cataonia.

Count Goblet d'Alviella,[128] quoting Perrot and Chipiez,[129] states that the Hittites introduced the Swastika on a bas-relief of Ibriz, Lycaonia, where it forms a border of the robe of a king or priest offering a sacrifice to a god.

[123] "Ceramic Art in Remote Ages."

[124] "Les Migration des Symboles," pp. 51, 52.

[125] "Det Saakaldte Hagebors," Copenhagen, 1877.

[126] "La Migration des Symboles," pp. 51, 52.

[127] Bull. de la Soc. d'Anthrop., December 6, 1888, XI, p. 671.

[128] "La Migration des Symboles," p. 51.

[129] "Histoire de l'Art dans l'Antiquité," IV.

ARMENIA

M. J. de Morgan (the present director of the Gizeh Museum at Cairo), under the direction of the French Government, made extensive excavations and studies into the prehistoric antiquities and archaeology of Russian Armenia. His report is entitled "Le Premier Age de Métaux dans l'Arménie Russe."[130] He excavated a number of prehistoric cemeteries, and found therein various forms of crosses engraved on ceintures, vases, and medallions. The Swastika, though present, was more rare. He found it on the heads of two large bronze pins (figs. 35 and 36) and on one piece of pottery (fig. 37) from the prehistoric tombs. The bent arms are all turned to the left, and would be the Suavastika of Prof. Max Müller.

[130] "Mission Scientifique au Caucase."

CAUCASUS

In Caucasus, M. E. Chantre[131] found the Swastika in great purity of form. Fig. 38 represents portions of a bronze plaque from that country, used on a ceinture or belt. Another of slightly different style, but with square cross and arms bent at right angles, is represented in his pl. 8, fig. 5. These belonged to the first age of iron, and much of the art was intricate.[132] It represented animals as well as all geometric forms, crosses, circles (concentric and otherwise), spirals, meanders, chevrons, herring bone, lozenges, etc. These were sometimes cast in the metal, at other times repoussé, and again were engraved, and occasionally these methods were employed together. ... Fig. 40 represents signs reported by Waring[133] as from Asia Minor, which he credits, without explanation, to Ellis's "Antiquities of Heraldry."

Fig. 38.

Fragment of bronze ceinture.

Swastika repoussé.

Necropolis of Koban, Caucasus.

Chantre, "Le Caucase," pl. 11. fig. 3.

The specimen shown in fig. 41 is reported by Waring,[134] quoting Rzewusky,[135] as one of the several branding marks used on Circassian horses for identification.

Mr. Frederick Remington, the celebrated artist and literateur, has an article, "Cracker Cowboy in Florida,"[136] wherein he discourses of the forgery of brands on cattle in that country. One of his genuine brands is a circle with a small cross in the center. The forgery consists in elongating each arm of the cross and turning it with a scroll, forming an ogee Swastika (fig. 13d), which, curiously enough, is practically the same brand used on Circassian horses (fig. 41). Max Ohnefalsch-Richter[137] says that instruments of copper (audumbaroasih) are recommended in the Atharva Veda to make the Swastika, which represents the figure S; and thus he attempts to account for the use of that mark branded on the cows in India (supra. p 772), on the horses in Circassia (fig. 41), and said to have been used in Arabia.

Fig. 40.

Swastika signs from Asia Minor.

Waring "Ceramic Art in Remote Ages," pl. 41, figs. 5 and 6.

Fig. 41.

Brand for horses in Circassia.

Ogee Swastika, tetraskelion.

Waring, "Ceramic Art in Remote Ages," pl. 42, fig. 20c.

[131] "Recherches Anthropologiques dans la Caucase," tome deuxième, péiode protohistorique, Atlas, pl. 11, fig. 3.

[132] Count Goblet d'Alviella, "La Migration des Symboles," p. 51.

[133] "Ceramic Art in Remote Ages," pl. 41, figs. 5 and 6.

[134] "Ceramic Art in Remote Ages," pl. 42, fig. 20c.

[135] "Mines de l'Orient," v.

[136] Harper's Magazine, August, 1895.

[137] Bulletins de la Soc. d'Anthrop. 1888, II. p. 678.

ASIA MINOR--TROY (HISSARLIK)

Many specimens of the Swastika were found by Dr. Schliemann in the ruins of Troy, principally on spindle whorls, vases, and bijoux of precious metal. Zmigrodzki[138] made from Dr. Schliemann's great atlas the following classification of the objects found at Troy, ornamented with the Swastika and its related forms:

Fifty-five of pure form; 114 crosses with the four dots, points or alleged nail holes (Croix swasticale); 102 with three branches or arms (triskelion); 86 with five branches or arms; 63 with six branches or arms; total, 420.

Zmigrodzki continues his classification by adding those which have relation to the Swastika thus: Eighty-two representing stars; 70 representing suns; 42 representing branches of trees or palms; 15 animals non-ferocious, deer, antelope, hare, swan, etc.; total, 209 objects. Many of these were spindle whorls.

Dr. Schliemann, in his works, "Troja" and "Ilios," describes at length his excavations of these cities and his discoveries of the Swastika on many objects. His reports are grouped under titles of the various cities, first, second, third, etc., up to the seventh city, counting always from the bottom, the first being deepest and oldest.

[...]

First and Second Cities.--But few whorls were found in the first and second cities[139] and none of these bore the Swastika mark, while thousands were found in the third, fourth, and fifth cities, many of which bore the Swastika mark. Those of the first city, if unornamented, have a uniform lustrous black color and are the shape of a cone (fig. 55) or of two cones joined at the base (figs. 52 and 71). Both kinds were found at 33 feet and deeper. Others from the same city were ornamented by incised lines rubbed in with white chalk, in which case they were flat.[140] In the second city the whorls were smaller than in the first. They were all of a black color and their incised ornamentation was practically the same as those from the upper cities.[141]

Fig. 42.

Fragment of lustrous black pottery.

Swastika, right. Depth, 23 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 247.

[...]

The Swastika, turned both ways 卐 and 卍, was frequent in the third, fourth and fifth cities.

The following specimens bearing the Swastika mark are chosen, out of the many specimens in Schliemann's great album, in order to make a fair representation of the various kinds, both of whorls and of Swastikas. They are arranged in the order of cities, the depth being indicated in feet.

The Third, or Burnt, City (23 to 33 feet deep).--[...]

Fig. 43.

Spindle-whorl with two Swastikas and two crosses. Depth, 23 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1858.

Fig. 44.

Spindle-whorl with two Swastikas. Depth, 23 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1874.

Fig. 49.

Sphere divided into eight segments, one of which contains a Swastika.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1999.

Fig. 51.

Biconical spindle-whorl with six Swastikas. Depth, 33 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1859.

Fig. 52.

Biconical spindle-whorl with two ogee Swastikas. Depth, 33 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1876.

Fig. 53.

Spindle-whorl with four Swastikas. Depth, 33 feet.

De Mortillet, "Musée Préhistorique," fig. 1240.

Fig. 54.

Spindle-whorl with one swastika. Depth, 33 feet.

De Mortillet, "Musée Préhistorique," fig. 1241.

[...]

The Fourth City (13.2 to 17.6 feet deep).--[...]

[...]

Fig. 55.

Conical spindle-whorl with three ogee Swastikas. Depth, 13.5 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1850.

Fig. 56.

Conical spindle-whorl with four Swastikas of various kinds. Depth, 13.5 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1879.

Fig. 59.

Biconical spindle-whorl with three ogee Swastikas. Depth, 13.5 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1990.

Fig. 60.

Biconical spindle-whorl with two Swastikas. Depth, 16.5 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1863.

Fig. 61.

Biconical spindle-whorl with five ogee Swastikas. Depth, 18 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1905.

Fig. 63.

Spindle-whorl having four ogee Swastikas with spiral volutes. Depth, 18 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1868.

Fig. 66.

Biconical spindle-whorl with three Swastikas and three burning altars. Depth, 19.8 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1872.

Fig. 67.

Biconical spindle-whorl with four Swastikas. Depth, 19.8 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1873.

Fig. 68.

Biconical spindle-whorl with three Swastikas of different styles. Depth, 19.8 feet.

Schliemann, "Ilios," fig. 1911.

Fig. 71.

Conical spindle-whorl with three ogee Swastikas. Depth, 13.5 feet.

Gift of Madame Schliemann. Cat. No. 149704, U.S.N.M.

[...]