The misconception that the so-called "Mezine swastika" is the oldest swastika in the world is repeated often on the internet. Simply looking at the artifact and looking at a swastika makes it clear the pattern on the artifact isn't a swastika, but non-connected bands of meanders! For a more in-depth analysis of this artifact and how its geometric pattern is definitively NOT swastika, refer to the article below:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/2020/08/the-mezine-carving-is-not-swastika.html

So, where were the world's oldest swastikas located and how old are they? Due to the inherent uncertainty of trying to precisely date archaeological findings, it is difficult to pinpoint a single artifact as being the most ancient swastika. In addition, new archaeological digs are always uncovering new artifacts which deepen our understanding of ancient societies.

However, there is enough information available for us to present over 100 examples of swastikas from the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Early Bronze Age.

The oldest swastikas I have been able to find are from the Samarra culture in the Fertile Crescent, dating back to around ~6200 BC during the Neolithic era. Over the next few thousand years, it continues to be used in the Halaf, Ubaid, and Uruk cultures in the region.

Beginning around ~5300 BC, several very ancient swastikas are found in the Danube Basin. This corresponds to the expansion of the Neolithic cultures and initial spread of agriculture into this region. These agriculturalists migrated from Anatolia and the Fertile Crescent—bringing the swastika with them. So far, we have found evidence of the swastika among the Vinča, Turdaș, Petrești, Cucuteni–Trypillia, Linear Pottery Culture (LBK) or Stroked Pottery Culture (SBK), Karanovo, and Sopot cultures of Neolithic and Chalcolithic Europe.

At some point within the period ~5450-4250 BC we find the first definitive evidence of the swastika in Iran at Tall-e Bakun and Bakun-related sites in the region. Starting around 4200 BC, the swastika is used in the Susa I period of western Iran (Ubaid culture), and from ~3800-3100 BC in the Susa II period (Uruk culture). By ~3350-3000 BC, the swastika had reached eastern Iran, where it became a popular motif in the Helmand Civilization (which encompassed parts of eastern Iran, western Pakistan, and Afghanistan). On Wikipedia it is claimed that a swastika found on the Lakh Mazar Inscription from eastern Iran may date back to ~5000 BC. However, I have not found any archaeological reports conclusively dating it, and suspect this date is exaggerated.

In the Early Bronze Age, by ~2800 BC the swastika appears in the Indus Valley Civilization (which began around ~3300 BC, although agriculture in the region dates back much further). During this same period, the swastika appears in the Namazga culture of Turkmenistan (~2750-2350 BC) and the Chinese Majiayao culture (~3300-2000 BC). The swastika's appearance in these societies is plausibly the result of cultural diffusion and trade arising from Chalcolithic and subsequent Bronze Age trade networks. Indeed, archaeologists continuously unearth evidence that ancient trade networks in the Old World and New World are far larger than once believed.

Of course, the swastika may have also arose independently in some regions, as it seems to have done in ancient Egypt during the Bronze Age—despite Egypt's millennia of cultural and genetic exchange with Fertile Crescent cultures.

***

There may be claims for even older swastikas, but repeating claims found on the internet without evidence is how falsehoods like the "Mezine swastika" get spread. The information about the artifacts posted below are, to the best of my abilities, backed up with reputable archaeological evidence.

The artifacts below are grouped into four categories. Within each category, they are sorted more-or-less by the average date of their date range.

In the first category, I have been able to find museum records or archaeological sources confirming the existence of ancient swastikas. The second category lists artifacts where I have thus far been unable to find or access archaeological writings discussing the swastika-bearing artifacts. Without an actual archaeological report or museum record describing the artifact, it is impossible to be sure that the claims people repeat on the internet are accurate.

The third category contains swastikas which are claimed to be considerably ancient by Wikipedia, news articles, books, and blogs. However, examination of actual archaeological sources casts doubt on the spectacular age claims.

The fourth category briefly mentions some so-called "swastikas" which are not swastikas at all: the Mezine mammoth tusk carving and the Turgay Triradial Triskelion geoglyphs. I have covered these two topics in further depth on their own pages.

***

This article is, to my knowledge, the first time a truly in-depth survey of the world's oldest swastikas has ever been published on the internet. I have tried to be as exhaustive as possible in including and researching every claim and lead I've come across.

For comments and discussion, please see the discussion post linked below. If you have any additional information for any artifact listed in the "Unconfirmed" section, we highly encourage you to share.

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/2021/09/worlds-oldest-swastikas-discussion-post.html

To return to the index of swastika articles, click here.

Summary of Artifacts

| Date | Artifact | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 6200-5800 BC | Samarra culture ceramics | Samarra, Iraq; Tell Baghouz, Syria |

| 5600-5000 BC | Halaf, Halaf/Ubaid, and Ubaid culture pendant, seals, and ceramic | Tepe Gawra, Iraq; surrounding region |

| 5450-4250 BC | Tall-e Bakun culture figurines and ceramics | Tall-e Bakun and Tol-e Nurabad, Fars Province, Iran |

| 5300-4350 BC | Vinča, Turdaș, and Petrești culture symbols | Middle Danube River Basin |

| 5100-4400 BC | Linear Pottery Culture (LBK)/Stroked Pottery Culture (SBK) ceramic | Hrbovice, Czechia |

| 4600-3900 BC | Cucuteni–Trypillia culture ceramics | Dniester and Dnieper River Basins |

| 4200-3100 BC | Ubaid/Uruk culture ceramics and seals | Susa and Tepe Giyan, Iran; surrounding region |

| 3550-2600 BC | Helmand Civilization ceramics and rock carvings | Eastern Iran, western Pakistan, southern Afghanistan |

| 3100-2050 BC | Majiayao culture ceramics | Upper Yellow River Basin |

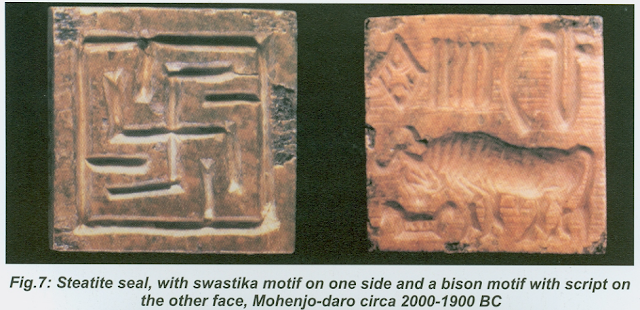

| 2800-2000 BC | Indus Valley (Harappan) Civilization seals and ceramics | Indus River Basin |

| 2750-2350 BC | Namazga culture seal | Altyn-Depe, Turkmenistan |

| 2500-2050 BC | Egyptian rock carvings and seals | Southwest Egyptian desert |

| Date | Artifact | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 6200-4900 BC | Ceramic | Devetashka cave, Bulgaria |

| 6200-4900 BC | Karanovo culture table | Kazanlak, Bulgaria |

| ~5000 BC | Ceramic | Riben, Bulgaria |

| 5450-4250 BC | Other Bakun-style ceramic | Tol-e Siyah, Forg Valley, Iran |

| 5000-4000 BC | Sopot culture ceramic | Bapska, Croatia |

| 4000-3000 BC | Ceramic | Altimir, Bulgaria |

| 4600-1750 BC | Other Cucuteni–Trypillia or Usatovo culture ceramics | Lower Dniester and Prut River Basins |

| 7000-3000 BC | Other European Neolithic artifacts | Mediterranean, Danube Basin, or Elbe Basin? |

| 7500-2200 BC | Other Ancient Chinese cultures? | China |

| 3500-2000 BC | Other Indus Valley Civilization artifacts | Indus River Basin |

| Date (claimed) | Date (likely) | Artifact | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12,000 BC | 2500-2050 BC | Ancient Egyptian artifact? | Ancient Egypt |

| ~5000 BC | 3550-2800 BC? | Lakh Mazar stone carving | Kooch, Iran, area |

| 8000-5000 BC | 3300-1200 BC | Petroglyphs | Gegham mountains, Armenia |

| 18,000+ BC | 200 BC - 1500s AD | Rock paintings | Telangana state, India |

| 8000+ BC | 2000 BC? - ? | Petroglyphs | Pedra Pintada, Roraima state, Brazil |

| Date (claimed) | Date (accurate) | Artifact | Location | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~15,000 BC | ~15,000 BC | Epigravettian mammoth tusk carving | Mezin, Ukraine | Conjoined bands of meanders, not a swastika |

| 6000-1000 BC | 800 BC - 1500s AD? | Turgay geoglyphs | Urpek, Kazakhstan; Turgay Trough, Kazakhstan | Triskelions, not swastikas |

Map of the major sites mentioned in the Confirmed (swastikas) and Unconfirmed (question marks) sections in this article.

Part 1. Confirmed Swastikas

Samarra culture

The most ancient swastika for which I could find reputable archaeological information belongs to the Samarra culture, which was centered around the city of Samarra in Iraq.

Ceramic bowl from Samarra, Iraq, in the collection of the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin (Ident.Nr. VA 13400). According to the museum's description, it dates to ~6200-5800 BC.

https://id.smb.museum/object/1743373/bemalte-schale

According to Wikipedia[1] the artifact was found by archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld in the excavation campaign of 1911-1914 and described by him in a 1930 publication.[2] The publication is behind a paywall and I am unable to access it to find further information... Loewenstein (1941)[5] says it is found on "p. 13, fig. 13 (13)" in Herzfeld's work.[2] Wikipedia incorrectly gives the date as 4000 BC, without explanation.[1]

In addition, the Wikipedia page cites an article by Freed (1981),[3] going on to imply the swastika on the bowl is a reconstruction and not authentic. The bowl was found in fragments and glued together by archaeologists, with missing pieces reconstructed. The very center of the swastika is part of this reconstruction, but enough of the swastika was present on the original fragments to demonstrate it did indeed exist. In addition, many other examples of the swastika appear in the Samarra culture, making it clear the swastika on the bowl is accurate and not a forgery or an incorrect reconstruction.

Image of the bowl without the reconstructed portions, showing that pieces of the swastika are still visible. Original image source unknown.

***

Numerous swastikas have been found in the Samarra culture and related Mesopotamian cultures.

Figure 278 in Braidwood et al. (1944).[4] The following figures are described as Samarran, although more detailed information is not provided. Skimming the Braidwood publication, it does not seem that they mention the source from where these illustrations were taken. I assume most, if not all, of them came from Herzfeld's series of publications on Samarra.

Plate C, Figure 4 from Loewenstein (1941).[5] Figure reproduced from Herzfeld (1930),[2] p. 16, fig. 12 (12). This looks very similar to Braidwood et al. (1944)[4] figure 279, but the breakage pattern is drawn slightly different, so it may be a different artifact.

Possible swastika on a fragment of pottery excavated by Ernst Herzfeld in Samarra, 1924. In the collection of the British Museum, registration number 1924,0416.442. The museum gives the date as 6500-6000 BC.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1924-0416-442

Plate C, Figure 3 from Loewenstein (1941).[5] Reconstruction of a ceramic fragment which was possibly a swastika. Figure reproduced from Herzfeld (1930),[2] p. 17, fig. 13 (13).

***

Swastika fragment and reconstruction, published as Fig. 18 1a and 1b in Soudský and Pavlů (1966).[102]

Description: "1 a-b - Samarra (habitat, trouvaille de surface de l'un des auteurs)". Translation: "1 a-b - Samarra (habitat, surface find of one of the authors)."

Fig. 18 3, 4, and 5 in Soudský and Pavlů (1966).[102]

Fourfold animal head motifs, showing a cross-like motif common in Samarran art (Fig. 18 3), a similar motif where the four animals have been abstracted into a swastika-like arrangement (Fig. 18 4), and a more complicated motif with swastika-like lines (Fig. 18 5). The second figure is labelled with "S.5" in the original source.[105]

Fig. 18 3: From Ernst Herzfeld, Die vorgeschichtlichen Töpfereien von Smarra, 1930, fig. 23.[2]

Fig. 18 4: Baghouz (R. Du Mesnil du Buisson, B., l'ancienne Corsôtê, Leiden 1948, pl. XXVII: 2).[105]

Fig. 18 5: Baghouz (R. Du Mesnil du Buisson, B., l'ancienne Corsôtê, Leiden 1948, pl. XXXI: 3).[105]

The latter two figures are from Tell Baghouz, which is another Samarra culture site in Syria.[106] Soudský and Pavlů (1966)'s[102] Figure 18 5 may be Figure 4 8b that was later published in Nieuwenhuyse (1999).[106] The paper[106] describes artifacts from the Louvre.

***

There are a few other swastikas and swastika-like motifs from Tell Baghouz, Syria, published by du Mesnil du Buisson:[105]

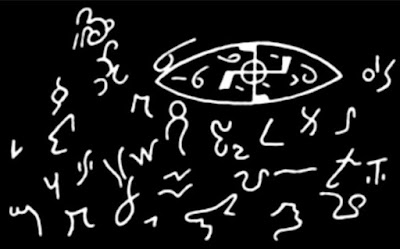

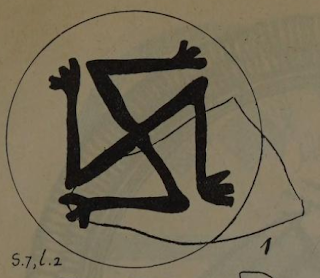

Plate XXV, Figure 1, S.7, l.2.

Description: "Coupes ornées de membres humains coupés, avec ou sans filet (1-5)." Translation: "Cups decorated with cut human limbs, with or without netting."

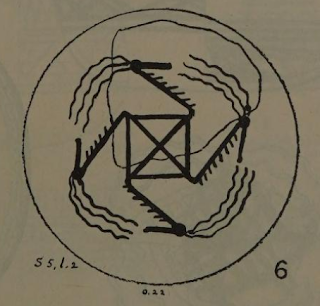

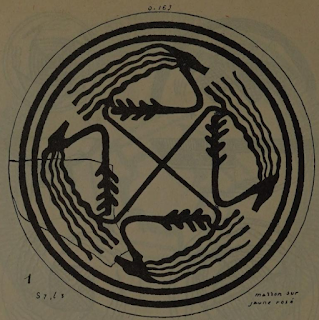

Plate XXVII, Figure 6. S5, l.2. 0.22.

Description: "Coupes à ornements dérivés du décor en bouquetins et filets, provenant du tell archaïque." Translaton: "Cups with ornaments derived from the decoration in ibex and nets, from the archaic tell."

Plate XXVIII, Figure 1. S7, l3. masson sur jaune rosé.

Description: "Coupes à décors dérivés des bouquetins, des filets, des lignes d'eau et des palmes. Tell archaïque." Translation: "Cups with decorations derived from ibex, nets, water lines and palms. Archaic tell."

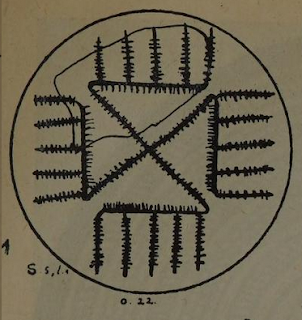

Plate XXXI, Figure 1. S s,l.1. 0.22.

Description: "Décors de palmes combinées avec la croix tournante (1). Tell archaïque." Translation: "Palm decorations combined with the rotating cross (1). Archaic tell." Compare to the reconstructed ceramic fragment from Tall-i Bakun published by Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 78, figure 25.

,%20Plate%20XXXII.PNG)

Plate XXXII.

Description: "Grande coupe à pied, à ornement en croix gammée, d'après des fragments provenant du tell archaïque." Translation: "Large foot cup, with swastika-shaped ornament, after fragments from the archaic tell."

On page 28-29, du Mesnil du Buisson gives his opinion on the possible meaning of the swastika.[105]

"La belle coupe aux cinq bouquetins (pl. XXVI), qu'il faut mettre en pendant avec celle des cinq oiseaux, représente plus exactement le gibier de la Mésopotamie (pl. XXIV). La palissade ou plesse du pourtour, on l'a vu, nous parait indiquer la capture des animaux.

Mais ici une autre particularité du décor doit retenir l'attention: le sujet tournant, qui ajoute à la signification; pour la magie, ce qui est dans un cercle, ce qui est encerclé, et ce qui tourne indéfiniment en rond ne surait s'échapper. Le possesseur du cercle est maître de ce qu'il contient, oiseaux ou cervidés. Le mouvement circulaire passe de plus pour n'avoir pas de fin. C'est un point qui est bien mis en lumière par l'étude de la croix gammée, symbole d'éternité et d'immortalité[30]. Dans le cas du gibier, comme des troupeaux, le mouvement sans fin doit sans doute assurer la multiplication indéfinie de l'espèce. Dans le décor d'une coupe de Suse et dans celui de deux fusaïoles d'Hissarlik (Troie)[31], la même idée a été rendue clairement par la reunion d'images de troupeaux et de croix tournantes.

Le site de Baghouz a livré une croix tournante faite de palmes, et combinée avec d'autres palmes (pl. XXXI, 1). Le sens magique paraît se référer au retour des eaux. La belle coupe à pied ornée d'une croix gammée formant en même temps des lignes brisées (pl. XXXII) est d'une signification identique. Le signe doit assurer indéfiniment le renouvellement de l'eau.

Reste un série de figures generalement tournantes, garnies de membres plus ou moins contournés (pl. XXV). Quartre bras forment une croix tournante. Nous avons vu là les membres coupés d'ennemis vaincus. Le but de ces représentations, parfois combinées avec des filets, était de s'assurer la victoire sur l'ennemi. Le mouvement tournant doit donner à cette victoire une durée indéfinie. Les femmes cernées par un cercle de scorpions, qui, vers cette époque, ornent certain fond de coupe de Samarra, nous paraissent de même se rapporter aux chances de la geurre. Celle-ci, en effet, mettait en cause la possession des femmes qu'il s'agissait alors de capturer.[32]

[30] Cf. notre article de la Revue Historique de l'Armée, II, 1946, "La croix gammée", p. 11-22.

[31] Ibid., figures, p. 14 et 17.

[32] Juges, V, 30."

Google translate:

"The fine cup with the five ibexes (pl. XXVI), which must be placed as a pendant with that of the five birds, represents more exactly the game of Mesopotamia (pl. XXIV). The surrounding palisade or plesse, as we have seen, seems to us to indicate the capture of animals.

But here another peculiarity of the decor must hold the attention: the rotating subject, which adds to the meaning; for magic, what is in a circle, what is encircled, and what turns indefinitely in circles cannot escape. The owner of the circle is master of what it contains, birds or deer. The circular movement passes moreover to have no end. This is a point which is well brought to light by the study of the swastika, symbol of eternity and immortality[30]. In the case of game, like herds, the endless movement must undoubtedly ensure the indefinite multiplication of the species. In the decoration of a cup from Susa and in that of two spindle whorls from Hissarlik (Troy)[31], the same idea was made clear by the combination of images of herds and revolving crosses.

The Baghouz site yielded a revolving cross made of palm leaves, and combined with other palm leaves (pl. XXXI, 1). The magic meaning seems to refer to the return of the waters. The beautiful footed cup decorated with a swastika forming at the same time broken lines (pl. XXXII) has an identical meaning. The sign must ensure the renewal of water indefinitely.

There remains a series of generally rotating figures, adorned with more or less curved limbs (pl. XXV). Four arms form a rotating cross. We saw there the severed limbs of vanquished enemies. The purpose of these representations, sometimes combined with nets, was to ensure victory over the enemy. The turning movement must give this victory an indefinite duration. The women encircled by a circle of scorpions, which, around this time, adorn certain bottoms of the Samarra cup, seem to us likewise to relate to the chances of war. This, in fact, called into question the possession of the women whom it was then a question of capturing.[32]

[30] Cf. our article from the Revue Historique de l'Armée, II, 1946, "La croix gammée", p. 11-22.

[31] Ibid., figures, p. 14 and 17.

[32] Judges, V, 30."

***

Pay particular attention to the fact that both left-facing and right-facing swastikas were used by ancient Mesopotamian cultures! This should once and for all end the annoying modern revisionism alleging there has always been some special distinction based on a swastika's orientation! If you are reading this article, you now have a duty to call people out when they parrot this nonsense.

Halaf culture, Halaf/Ubaid transitional culture, and Ubaid culture

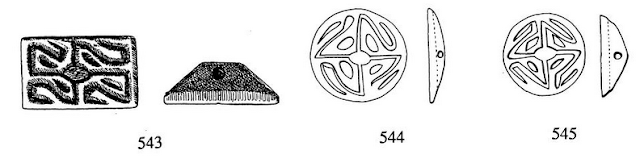

Pendant from Tepe Gawra (stratum XX), in northern Iraq, published by Tobler (1950),[96] Plate CLXXIV, Figure 56. According to the archaeological report by Tobler (1950, page 4),[96] stratum XX dates to the same period as the Halaf culture.

I can't find much information regarding radiocarbon dating for this stratum. Lawn (1973)[98] dated level XIX to ~5,134-4,970 BC and reiterated that level XX was from the Halaf period. Radiocarbon dating by Akkermans (1991)[98] dates the beginning of the Early Halaf period to 5100-5000 BC. Akkermans (1991)[98] says the Halaf period was conventionally believed to begin by ~5600 BC, but he rejects this in light of his radiocarbon data. Without more precise information, it seems reasonable to give a broad date range of ~5600-5000 BC for this artifact. Wikipedia describes Tepe Gawra and this period as belonging to the "Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period".[107]

,%20Plate%20CLIX,%20Figure%2022.PNG)

Swastika-like basketweave motif on a seal from Tepe Gawra. Illustration from Tobler (1950),[96] Plate CLIX, Figure 22. Stratum not specified.

,%20Plate%20CXLIX,%20Figure%20452.PNG)

Swastika-like designs from Tepe Gawra illustrated in Tobler (1950),[96] Plate CXLIX, Figure 452. From strata XVI and XV.

Peasnall and Rothman (2003) describe strata XVI and XV as belonging to the beginning of the Ubaid period of the site.[180]

***

The book Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] is a catalog of ancient seals and stamps from the "Near East", dating from the late Aceramic Neolithic to early Bronze Age, in the collection of Lenny Wolfe and family.

Figure 138 in Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] is described as: "cruciform design. Cross with central square. Square lines extend to crude swastika with parallel radiating lines above." 5th millennium, Chalcolithic, Halaf or early Ubaid periods. North-West Syria/South-East Anatolia/North Iraq.

The image in the scan I found is very pixelated, and it's not clear enough to determine whether the design is a swastika.

The catalog[108] contains a brief discussion regarding artifacts similar to Amorai-Stark's figure 138:

"The swastika design (a version of "point group 4" layout) and the radiating cross design are features of early Ubaid period cf. Von Wickede 1990: No. 212 (Tepe Gawra, early Ubaid period); WFC No. 175. [...] Cf. also Amorai-Stark 1993: SBF No. 3 (carinated hemispheroid, swastika design)."

I was not able to find a copy of von Wickede (1990)[109] or Amorai-Stark (1993).[110] (Amorai-Stark (1993) is not included in the bibliography of the Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] catalog, but presumably it's the work I cite.) Figure 175 in Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] is a basketweave that is not particularly swastika-like, since it's diagonal and therefore does not truly have the terminal "hooks" that a swastika does.

Tall-e Bakun culture

Without doing an exhaustive search for swastikas in ancient Iran, I located some from the site of Tall-e Bakun (Tall-i Bakun), outside the village of Kenareh, near Marvdasht, Iran. According to Alizadeh (2006),[34] the Bakun A cultural phase dates to 4500-4100 BC. However, radiocarbon dates in Weeks et al. (2010)[183] suggest an older date. Dates for Tall-e Bakun B spanned ~5360-4700 BC and lower levels of Tall-i Bakun A corresponding to the Middle/Late Bakun transition period date to ~4500-4250 BC.[183] Radiocarbon dates for the Bakun period at the site of Tol-e Nurabad shows it may have spanned roughly from ~5450 BC[183] or ~4800-4600 BC[184] to 4250 BC.[183]

Figure 60A in Alizadeh (2006),[34] showing a clay human figurine. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A19779; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number (Register Number) PPA 371.

Alizadeh (2006)[34] lists it as being from level III of the Tall-e Bakun A mound, Building VIII, Room 7. However, the original excavators of the figurine, Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] list it as coming from "level IV, surf."

Figure 60B in Alizadeh (2006),[34] showing a clay human figurine. Excavated from building V, room 1, level III of the Tall-e Bakun A mound. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Field Number (Register Number) PPA 372.

The University of Chicago Oriental Institute has many other artifacts from Tall-i Bakun, a number of which have swastikas.

Photo of the figurine shown as an illustration in figure 60A in Alizadeh (2006).[34] In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A19779; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 371.

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/56ec96a1-7956-4b1e-85f5-b9a7d78e790f

Additional photos:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:UC_Oriental_Institute_early_Persian_03.JPG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:UC_Oriental_Institute_early_Persian_02.JPG

Clay figurines from Tall-i Bakun with swastikas. It shows the two artifacts from 60A and 60B in Alizadeh (2006),[34] shown above, and another artifact with two "basket-weave" style swastikas. Photo Number 025116 in the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Figurine with basket-weave swastikas is shown in a photograph in plate 6, figure 17 of Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] and listed as having Field Number 374.

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/dd6b6448-cc5e-4b34-83b0-5a2f8ec1b61d

Cropped from a photo showing figurines from Tall-i Bakun levels III and IV. One of the sides of the figurine shown in figure 60B in Alizadeh (2006).[34] Photo Number 025059 in the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. It is not clear what the registration numbers of the specific figurines are.

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/4ceb012e-fe82-495b-9541-39c8cf8c6139

Ceramic fragment from Tall-i Bakun A with swastika. OIM # A49897 in the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A49897; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number unknown (perhaps PPA 3305 shown in plate 74, figure 1, of Langsdorff and McCown (1942).[164])

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/9b507113-b88a-4357-9b5f-85c141f9aae9

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 74, figure 1, field number 3305. I was unable to find this artifact in the University of Chicago Oriental Institute's collection. Their website lists PPA 3305 (Registration Number A20257) as a sling shot from Tall-i Bakun. It may be the artifact shown above in a photo (Registration Number: A49897; Accession Number: 2110).

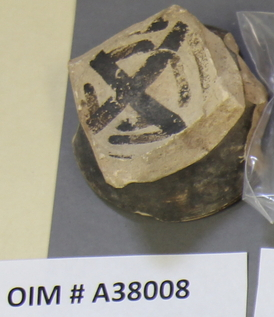

Ceramic fragment from Tall-i Bakun with swastika. OIM # A38008 in the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A38008; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2962. Shown in plate 28, figure 6 of Langsdorff and McCown (1942).[164]

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/2e963cd9-049e-496c-b0db-212f4ba7d6fe

Ceramic fragment from Tall-i Bakun, which may have had a swastika or motif with more than four "arms". OIM # A39275 in the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A39275; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 5220.

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/5e10dc85-1975-4f88-b860-149e9b3f488c

Illustration of the ceramic fragment above (OIM # A39275), published in Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 78, figure 28. Artifact is listed as having field number 5220; excavated from Trench I, 10-20 m., ±0 m.; level I.

Based on the geometry, the authors suggest it originally had six hooks.

Ceramic bowl from Tall-i Bakun A with "basket-weave" style swastikas. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A20128; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2120.

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/5f6335a9-db2e-4f7f-98c6-b1a550bad9b1

Ceramic fragment from Tall-i Bakun with swastika-like symbol. OIM # A38427 in the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A38427; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2418.

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/df1910a1-de65-42be-91b0-8bf3eb88c5da

Illustration of the ceramic fragment above (OIM # A38427), published in Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 36, figure 11, field number 2418.

***

,%20figure%2039%20E.PNG)

Figure 39E in Alizadeh (2006).[34] Ceramic with a continuous band of swastikas. Register No. unknown. Excavated from Sq. BB 62. Level 3.

,%20figure%2041%20C.PNG)

Figure 41C in Alizadeh (2006).[34] Ceramic with a continuous band of swastikas. Register No. TBA 705. Excavated from Sq. BB 38, Rm. 5. Level 3.

Note that the breakage patterns are the exact same in both illustrations, and therefore it must be the same artifact. Thus, the information about where it was excavated is conflicting.

***

After Ernst Herzfeld's small-scale excavation at Tall-i Bakun A in 1928, Alexander Langsdorff and Donald McCown were the first to conduct extensive archaeological digs at the site, in 1932.[164] Their 1942 publication contains numerous illustrations and photos of artifacts recovered.[164]

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 1, figure 9, field number 3564. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Field Number: PPA 3564. The only record for this artifact in the online collections appears on a note card.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/7d0be996-1bd0-478f-bdfe-f9862165f62f

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 1, figure 11, field number 3297. Ceramic with multiple swastika-like crosses. For example, see the left hook on the Susa I ceramic fragment (Numéro principal: AS 14773) for a similar brush stroke pattern. I was unable to find further information about this artifact in the University of Chicago Oriental Institute's collection.

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 31, figure 2, field number 3539. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A20270; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 3539.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/8da0e7d6-99c7-4a99-a87d-1495ad415780

Photograph of the artifact above. (Registration Number: A20270; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 3539.)

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 44, figure 7, field number 2893. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A39003; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2893. The design on the artifact cannot be clearly seen in the University of Chicago's photograph.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/0080b83d-193e-4007-8567-e20069c612bf

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 72, figure 9, field number 2503. I was unable to find further information about this artifact in the University of Chicago Oriental Institute's collection.

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 73, figure 4, field number 3715. Reconstructed pattern on a fragment of pottery that the authors suggest was a swastika. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A38471; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 3715.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/267b5829-7caa-41f7-8b74-cd4b325927e9

Photograph of the artifact above. (Registration Number: A38471; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 3715.)

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 78, figure 25, field number 4606. Excavated from S. of Rm.s IV 1, V2, deepest level; level I. I was unable to find further information about this artifact in the University of Chicago Oriental Institute's collection.

Reconstructed pattern on a fragment of pottery. Somewhat swastika-like; compare to the reconstructed Samarra culture ceramic fragment from Tell Baghouz, Syria, published by du Mesnil du Buisson (1948)[105] in plate XXXI, figure 1.

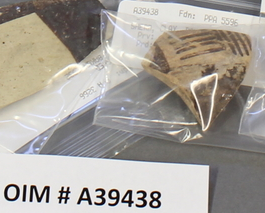

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 78, figure 32, field number 5596. Reconstruction of a basket-weave swastika. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A39438; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 5596.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/f08fef2f-4442-4b49-99c7-3e0803e7caa7

Photograph of the artifact above. (Registration Number: A39438; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 5596.)

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 79, figure 21, field number 5369. Swastika-like motif. I was unable to find further information about this artifact in the University of Chicago Oriental Institute's collection.

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 80, figure 21, field number 2984. Fragment of a basket-weave swastika. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A38158; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2984.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/c16047c7-b211-46ec-82af-e9af767fe49f

Photograph of the artifact above. (Registration Number: A38158; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2984.)

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 80, figure 25, field number 2956. Swastika-like fragment that the authors reconstructed as a non-swastika for unclear reasons. In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A38153; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2956.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/6bbc9729-a2f4-4f1f-a04b-9d92cfc22672

Photograph of the artifact above. (Registration Number: A38153; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 2956.)

Langsdorff and McCown (1942),[164] plate 81, figure 23, field numbers 259, 260b, 269, 7. This seal appears to be reconstructed from 4 fragments? In the collection of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Registration Number: A19729; Accession Number: 2110; Field Number: PPA 269. There is no photo of the artifact.

https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/9e0273f4-efb5-4055-9ed2-900417c383a8

For the sake of thoroughness, here is a table for the artifacts illustrated above, containing a subset of the information provided by Langsdorff and McCown (1942).[164]

| Field No. | Registration No. | Orientation | Artifact | Provenance | Level | See Page | Plate | Figure No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPA 3564 | ? | 1 left-facing | ceramic | Rm. III 4 | III | 25 | 1 | 9 |

| PPA 3297 | ? | multiple, swastika-like, right-facing? | ceramic | Rm. XII 4, fill(?) | III | 34 f. | 1 | 11 |

| PPA 374 | ? | 2 left-facing | human figurine | O 28, +3.31 m. | surf. | 64 | 6 | 17 |

| PPA 372 | ? | 1 left-facing, 1 right-facing | human figurine | Rm. V 1 | III | 17, 64 | 7 | 1a |

| PPA 372 | ? | 3 left-facing, 2 right-facing | human figurine | Rm. V 1 | III | 17, 64 | 7 | 1b |

| PPA 371 | A19779 | 2 left-facing | human figurine | N. of Rm. VIII 7, +2.2m. | IV, surf. | 64 | 7 | 4a |

| PPA 3305? | A49897 | right-facing | pottery | K 28, level of Rm. IV 2 | III | 52 | 74 | 1 |

| PPA 2962 | A38008 | right-facing | pottery | Rm. XVII 4 | IV | 38, 56 | 28 | 6 |

| PPA 5220 | A39275 | right-facing, non-swastika? | pottery | Trench I, 10-20 m., ±0 m. | I | N/A | 78 | 28 |

| PPA 2120 | A20128 | 2 left-facing | pottery | FSP -- A | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| PPA 2418 | A38427 | 3 left-facing | pottery | N 29, +2.02m. | base IV | 40 | 36 | 11 |

| ? | ? | 4+ right-facing | pottery | Sq. BB 62 | Level 3 | ? | ? | ? |

| ? | ? | 4+ right-facing | pottery | Sq. BB 38, Rm. 5. | Level 3 | ? | ? | ? |

| PPA 3539 | A20270 | left-facing | pottery | Rm. XVII 3 | IV | 39 | 31 | 2 |

| PPA 2893 | A39003 | right-facing | pottery | Trench I, 10-20 m., ±0 m. | I | 43 | 44 | 7 |

| PPA 2503 | ? | right-facing | pottery | Rm. VII 3 | III | N/A | 72 | 9 |

| PPA 3715 | A38471 | right-facing | pottery | Trench I, 10-20m., +.45 m. | I | 51 | 73 | 4 |

| PPA 4606 | ? | left-facing, potential swastika? | pottery | S. of Rms. IV 1, V 2, deepest level | I | N/A | 78 | 25 |

| PPA 5596 | A39438 | right-facing | pottery | Rm. VIII 3 | III | N/A | 78 | 32 |

| PPA 5369 | ? | left-facing | pottery | unknown | unknown | N/A | 79 | 21 |

| PPA 2984 | A38158 | right-facing | pottery | M 26-27, +2.5 m. | IV | 53 | 80 | 21 |

| PPA 2956 | A38153 | right-facing | pottery | Rm. XII 2 | III | 53 | 80 | 25 |

| PPA 259, 260b, 269, 7 | A19729 | right-facing | stamp/seal | Rm. II 4 (259, 260b); Rm. IV 3 (269); Rm. XIII 1 (7) |

III (259, 260b); III (269); IV (7) |

17, 20, 67 f. | 81 | 23 |

***

Weeks et al. (2010)[183] and Weeks et al. (2006)[184] published two illustrations of swastikas from the site of Tol-e Nurabad, Iran. These were excavated from the phases A18-A14 of the site, which correspond to immediately after the end of the Neolithic era and into the Late Bakun period.[183][184][185] Radiocarbon dating proved difficult, but based on comparisons with radiocarbon dates from Tall-i Bakun B, the Bakun period of Tol-e Nurabad may have spanned roughly from ~5450 BC[183] or ~4800-4600 BC[184] to 4250 BC.[183] More specifically, Phase A16 radiocarbon dated to ~4780-4490 BC.[183]

Artifact TNP 1101, excavated from Phase A16[184] of Tol-e Nurabad, Iran. Ceramic fragment with a swastika inside two circles. Published in figure 16.5 of Weeks et al. (2010)[183] and figures 3.82-3.97 of Weeks et al. (2006).[184]

Artifact TNP 1006, excavated from Phase A15[184] of Tol-e Nurabad, Iran. Ceramic fragment likely of a swastika. Published in figure 16.5 of Weeks et al. (2010)[183] and figures 3.82-3.97 of Weeks et al. (2006).[184]

***

The swastika is described as one of the motifs found on pottery at Toll-e Rahmatabad, Iran. Azizi Kharanaghi et al. (2017)[192] describe this Middle Bakun Period site as the following:

"The prehistoric Bakun culture of Fars during the Chalcolithic period (i.e. the fifth millennium BCE), is unparalleled among the contemporaneous cultures of Iran with regard to the diversity of its pottery techniques and creating specific geometric, animal, and human motifs. In this period, very diverse forms of pottery were produced by full-time expert potters. Toll-e Rahmatabad, located in the Kamin Plain of Pasargadae district, is one of the prehistoric regions which acted as a pottery production center during the fifth millennium BC in the Middle Bakun Period. In archaeological excavations carried out in this site during three seasons, direct archeological evidence of production and thousands of pieces of pottery belonging to the mentioned cultural period were discovered. In the present study, the relationship between the form and design in these ceramics was examined by using statistical linear models and SPSS Software. The significance level in all the tests was set at 0.05. The results of data analyses indicated a significant relationship between the form and design of pottery during the Middle Bakun Period at Toll-e Rahmatabad"

Figure 6 in Azizi Kharanaghi et al. (2017).[192] Description: "All types of human, animal, geometric, and plant designs on the middle Bakun Period potteries of Rahmatabad (Fazeli and Azizi Kharanaghi 1999: Figs. 6 and 7)."

The "Fazeli and Azizi Kharanaghi 1999" citation seems to be a typo. In the references, there is only Fazeli and Azizi Kharanaghi (2008).[193] Furthermore, the first excavations at Toll-e Rahmatabad did not occur until 2005.[192] Fazeli and Azizi Kharanaghi (2008)[193] is noted as being in the Farsi language, and I have not been able to find a copy of it.

Vinča, Turdaș, and Petreşti cultures

Vinča culture

The Vinča culture existed in the middle part of the Danube River Basin. The habitation at Vinča itself is dated to around 5300-4500 BC.[6][7][8][9] The Vinča culture is descended from the Starčevo culture, which arrived in the region around 6200 BC and represents the initial Neolithic migration into the Danube Basin.[7]

Searching the internet, it is easy to find many images of "Vinča symbols" (which include the swastika), but it is very difficult to trace them back to the original publications to confirm their authenticity. Due to accurate archaeological information being inaccessible and hidden behind academic paywalls, this has allowed the spread of so much misinformation and so many outrageous pseudo-science blogs. But, since these are basically the only results that regular people come across while searching the internet, these are the sources people read and the ideas they come to believe in—demonstrating just how terrible the Western academic system is at disseminating knowledge. Anyway...

From what is written in Palavestra (2017),[6] it seems like many of the illustrations of Vinča artifacts originate from the papers Todorović and Cermanović (1961)[10] and Todorović (1969).[11] I am unable to find either of these papers online.

"Basket-weave" style swastika-like pattern from pottery from Banjica, Serbia. Cropped from Figure 4 in Palavestra (2017)[6], which is reproduced from Plate I in Todorović (1969).[11]

Figure 21 in Haarmaan (2009).[32] Description: "Specimen of a one-sign inscription on an amphora fragment from Potporanj-Kremenjak, Serbia, Early Vinča culture (after Starović 2004: 44)".

I can't find a full pdf article of Haarmaan (2009)[32] and therefore can't see precisely what publication Starović (2004) is, but I presume it is the paper he presented at the Novi Sad symposium.[33]

This swastika ended up in one of the many catalogs of Vinča symbols. As Merlini (2009) describes:[20] "Fig. 4.26 – Joanović’s corpus of inscribed objects from At in Vršac and Kremenjak (Republic of Serbia). (After Joanović 1981: 134, 135)." The symbol in group I, row 4, column 5 appears to be the swastika on the artifact above. Further description from Merlini:

"In 1981 Šarlota Joanović published a list of 233 signs from objects in the national museum of Vršac. They derive mainly from the sites of At in Vršac and Kremenjak (near Potporani, Republic of Serbia), both belonging to the Vinča B2 and Vinča C phases (Joanović 1981: 134, 135).8

8 For the utilization of the script at Vršac At, see 9.C.b "The Vinča C as the culture of the greatest sign production"."

***

Turdaș culture

The Vinča culture is sometimes called the Vinča–Turdaș culture (or Turdaș–Vinča culture), to denote the possible cultural similarities of the core Vinča area and the core cultural area surrounding the Luncă archaeological site located in the commune of Turdaș, Romania.

However, in recent publications, the lead archaeologist studying the site says the Turdaș culture should be considered a distinct culture from the Vinča culture.[12][144] In the paper, it states the earliest inhabitation at the Turdaș site dates back to the same time period as Vinča,[12] and another paper suggests the oldest phases at Turdas could date to ~5200-5100 BC.[144] Prior work suggested the oldest part of the Turdaș site dates back to only 5000-4900 BC.[13][14] Most of the publications about Turdaș are published only in the Romanian language, and there are certain disputes raised about plagiarism, authorship, methodology, and the dating chronology of the site.[14] (Yes, even professional academics can be just as petty as random internet people on forums debating about their preferred hypotheses).

Cropped from figure 11 in Winn (2003).[15] Symbols found in Turdaș (Tordos), Romania, reproduced from the notebook of 19th century archaeologist Zsófia Torma, who excavated the site.

Note 2 from Winn (2003):[15][17]

"This important site, situated on the south bank of the Maros (Mures) River, is known as Tordos in Hungarian and Turdas in Romanian. Many of the unusual artifacts from this site are known only from the unpublished but meticulously illustrated notebook of Zsófia Torma. The Tordos examples herein (not previously seen nor published by the author in his corpus of signs) are taken from this work, which was made available to me through the kindness of N.Vlassa of Muzeul de storie al Transilvaniei in Cluj."

This seems to suggest the illustration Winn included from Torma may have previously been unpublished. Winn's bibliography lists a 1941 publication which seems like it may contain other illustrations made by Torma.[18][15] Torma published at least one work on Turdaș.[26][145]

I can't find much information about Winn on the internet. He served as a professor of anthropology at the University of Southern Mississippi from 1975 to 1995.[19] According to Marco Merlini (the coordinator of the Prehistory Knowledge Project website on which Winn's 2003 and 2004 writings were published digitally), Winn received a PhD in 1973, had a career in archaeology (and at times collaborated with archaeologist Marija Gimbutas), and spent much of his career creating a catalog of different Vinča symbols.[20][21]

Two swastikas categorized as DS 149 and DS 151 in Winn's updated catalog from 2004.[22] The artifacts they were found on are not described. These two signs were Sign 70 and Sign 79, respectively, in Winn's 1981 inventory, which is reproduced as Fig. 4.18.b in Merlini (2009).[20]

Haarmann (1995)[29] also produced a catalog of symbols from the so-called "Old European script". Haarmann's OE 135 and OE 133, respectively, correspond to Winn's symbols above (republished in Merlini (2009)[20] as Fig. 4.20.f). Lazarovici (2004)'s catalog lists the left-facing swastika as symbol 84 (reproduced in Fig. 4.22 in Merlini (2009)[20]). This appears to be Lazarovici (2004b)[30] in Merlini's bibliography;[25] a paper presented at a symposium and published in a journal in 2008.[31]

Lazarovici's 2005 catalog (reproduced as Fig. 4.23 in Merlini (2009)[20]) is much more extensive. Left-facing swastika is symbol 84, superimposed left-facing swastikas are symbol 84e, right-facing swastika is symbol 84a, right-facing swastika with two branches/arms on each part of the cross is symbol 84b, right-facing swastika with three branches/arms on each part of the cross is symbol 84c, and a left-facing rotated swastika with arms bent at an angle larger than 90 degrees is symbol 84a1. A swastika-like symbol appears as symbol Om 36. I think this may be how the symbols were cataloged in Lazarovici's Zeus program in 2005—there does not appear to be a particular paper cited.

***

Around 2008 Merlini announced he was making his own searchable database of symbols found in the ancient Danubian cultures. This database is called "DatDas (Databank of the Danube script)".[23][24] As far as I can tell, the database has not yet been made publicly available. Merlini said Gheorghe Lazarovici's database "Zeus" was the only other queryable database containing symbols and signs of the Danubian culture.[23] I haven't found this database online either—it might only be available to researchers at the Romanian university where it is maintained? Its origin is briefly described in Luca and Suciu (2008):[27]

"The archaeological material was studied quantitatively and qualitatively. Description of the ceramic material was carried out, considering the following: shapes, rim variants, bases and handles, decoration (technique and type); sort, blending (mixture), surface treatment or burned and colours of potsherds. The structure was designed in the Bazarh system, in the Department of Prehistory, Cluj University (since 1984). After 1988 the work with the database was carried out by means of a more comprehensive system, “ZEUS” (TARCEA and LAZAROVICI, 1996)."[28]

***

Petreşti culture

In the Chalcolithic era, the site of Turdaș-Luncă was subsequently used by the Petreşti culture.[26][144] Some radiocarbon dating of the Petreşti layer of the site dates to ~4600-4350 BC.[144][146]

Petreşti culture loom weight excavated from Turdaş-Luncă. Published as figure 10 7a-b of Luca (2001)[26] and republished on page 389 in Merlini (2009).[23] Excavated from "Zona centrală (Planul 1, punctul A). Nivelul III". "Central area (Plan 1, point A). Level III."[26]

The following is the description in Merlini (2009).[23]

"I also did not insert a Petreşti loom weight from Turdaş, although it is inscribed with a swastika with double arm and a tri-line, because the marks are located on different faces. According to the discoverer, the swastika with double arm is a distinct mythological representation of the Neolithic communities from Near East to the Danube valley. Regarding a possible interpretation, he advanced a numeric significance or a beneficial symbolism (Luca 2001a: 55).[26]

Fig. 6.29 – A Petreşti loom weight from Turdaş was not introduced in the databank because the single marks are situated on different faces. (After Luca 2001a,[26] fig. 10/7a-7b)."

Petreşti loom weight from Turdaş published as figure 11 (4) in Luca (2001).[26] Excavated from Turdaş-Luncă in the layer "Locuinţa L2/1994–1995, nivelul III, suprafaţa S II". "Dwelling L2/1994–1995, level III, surface S II".

***

In summary, reputable academic sources confirm the swastika and its variants were found in the Vinča, Turdaș, and Petreşti cultures. However, it has been difficult to find publications which give more detail on the specific artifacts bearing swastikas and the locations where they were found. The charts floating around the internet of Vinča symbols likely come from one of the catalogs referenced above. Another noteworthy finding is that, again, both left-facing and right-facing swastikas, as well as a rotated swastika, appear.

Linear Pottery Culture (LBK)/Stroked Pottery Culture (SBK) transitional culture, or SBK culture

During the Neolithic, present-day Czechia was a major center of the agriculturalist Linear Pottery Culture (Linearbandkeramische Kultur; abbreviated as LBK in English).[74] The Neolithic period in Czechia dates back to approximately ~5500-4200 BC.[74][75][115] Archaeologists have determined that the LBK, which covered a large geographic area, eventually gave rise to various regional cultures. This includes the Stroked Pottery Culture (Stichbandkeramik; SBK) in Saxony and Bohemia, which arose around 5100-4950 BC and lasted until approximately 4600-4400 BC.[115][116]

The site of Hrbovice was used during the transition from LBK to SBK and in later phases of the SBK.[115][117]

LBK/SBK swastika reconstruction published in figure 11 (10) of Soudský and Pavlů (1966).[102]

The illustration above is of a reconstructed fragment of what was likely a swastika, from pottery excavated at Hrbovice, Czechia. This illustration was published in Soudský and Pavlů (1966).[102] In the paper, the authors discuss broadly their interpretation of motifs in the LBK/SBK culture and Neolithic Anatolian culture. The artifact with the swastika is not discussed in depth nor does the paper contain any information about its date, catalog number, or archaeological paper where it was first published. Presumably it was discovered in an excavation by Soudský or Pavlů.

In 1974, an illustration of this swastika and other motifs which were seen in Soudský and Pavlů (1966)[102] was published in a book by Marija Gimbutas.[103] Her illustration does not make it clear that two of the hooks are reconstructions.

Around 2002, another version of Gimbutas's illustration was reposted on the website Archaeometry by Fernando Coimbra,[73] where he listed the artifact as being from Bylany, Czechia, with the following description:

"The oldest swastika I know of is depicted on a ceramic vessel from Bylany, Bohemia and belongs to the 6th millennium BC."[73]

It is unclear where Coimbra found this image, as it differs from the figure in Gimbutas's 1974[103] and updated 1982 editions.[104]

In any case, as evidenced from the swastika's presence in other Neolithic cultures such as the Sopot and Vinča and Turdaș, the swastika migrated up the Danube Basin. Therefore, the LBK/SBK swastika cannot be the oldest swastika, as Coimbra's source claimed.

Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was a Neolithic culture who went northward of the Carpathian mountains and into the Dniester and Dnieper River Basins, rather than up the Danube (like the Vinča and Turdaș cultures). In the millennium of the 3000s BC, the Trypillia branch of this culture, in particular, constructed what were likely the largest cities on Earth during this time period.[41] Swastikas have been found on ceramics from the site of Cucuteni, Romania.

Fig. 122 published in Petrescu-Dîmbovița and Văleanu (2004),[42] from the Cucuteni A period. Description:

"Fig. 122. Ceramică pictată din faza Cucuteni A. Fragmente şi butoni de la capace (1-9). Din locuinţa 11/14 (2)."

Google translate:

"Fig. 122. Painted pottery from the Cucuteni phase A. Fragments and buttons on the lids (1-9). From house 11/14 (2)."

Radiocarbon dates in Lazarovici (2010)[43] date Cucuteni A1-A2 to ~4600-4000 BC and Cucuteni A3-A4 to ~4300-3900 BC. Petrescu-Dîmbovița and Văleanu (2004)[42] is written in the Romanian language; further examination of this work may more precisely indicate which layer of Cucuteni A the artifact was found in.

Ubaid culture, Ubaid/Uruk transitional culture, and Uruk culture

The Ubaid culture was a broad archaeological culture, trade network, or "period" in Mesopotamia and western Iran. The city of Susa became a major site in western Iran by the end of the 5th millennium BC.[181] The Susa I (or Susa A) period of the city corresponds to the Ubaid period,[181] beginning around ~4200 BC.[182] The Susa II period of the site corresponds to the Uruk period of Mesopotamia, lasting from ~3800-3100 BC.[182]

Ceramic from the Susa I period, discovered in 1908-1909 at the necropolis on the acropolis mound, Susa, Iran. According to the Louvre museum, the Susa I period dates to 4000-3500 BC or 4200-3800 BC. In the collection of the Louvre, Paris, France. Numéro principal: SB 3153, Autre numéro d'inventaire: AS 11617.

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010122788

Loewenstein (1941)[5] says the ceramic above is described in Jacques de Morgan, Le Prehistoire Oriental, (Paris, 1925-27), vol. 2, p. 266.

Ceramic from the Susa I period, discovered at the necropolis on the acropolis mound, Susa, Iran. In the collection of the Louvre, Paris, France. Numéro principal: SB 3203.

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010177180

Seal from Susa I with one right-facing and one left-facing swastika. In the collection of the Louvre Museum, Département des Antiquités orientales. Numéro principal: SB 5686. N° de fouille: N 803. Excavated in 1933.

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010179507

The Louvre entry and Encyclopædia Iranica[118] state the artifact is described in the work Amiet (1977),[119] although I have not found this work online. Encyclopædia Iranica[118] published an illustration of this seal in their Plate XXXVII, Figure 3, and indicates it comes from the Susa I period (late Chalcolithic).

Plate C, Figure 8 from Loewenstein (1941).[5] Loewenstein says the figure is reproduced from Jacques de Morgan, without further description.

The same ceramic fragment shown above. From the Susa I period, c. 4000-3500 BC. In the collection of the Louvre Museum. Numéro principal: AS 14773. Numéro catalogue: MDP XIII, 194.

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010244160

Swastika-like stamp from the Susa II period (3800-3100 BC) in the collection of the Louvre. Numéro principal: SB 5466. N° de fouille: G 1.

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010179289

***

Stamp or seal from Tepe Giyan (level V, period C), Iran. The museum page gives a date of 4000-3000 BC, and says the artifact is from excavations conducted by Roman Ghirshman in 1933, 1934, and 1937.

In the collection of the Louvre, Paris, France. Numéro principal: AO 16323.

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010141149

Judging by the following Flickr page, the Louvre may have been marketing this as the world's oldest swastika at some point?

https://www.flickr.com/photos/73553452@N00/4444150181/in/photostream/

Regarding the date of Tepe Giyan, it is difficult to find freely-available research papers on the internet. Mutin (2012)[39] suggests Tepe Giyan V dates back to "the late sixth to early fifth millennia BC"—i.e. ~5300-4700 BC. Table II in McCown (1942)[40] divided the Tepe Giyan V layer into VA-VD. He sas Tepe Giyan VC overlaps with the Susa I period. As we saw above, the Louvre Museum dates the Susa I period to ~4200-3500 BC. More recent papers would likely give us a more precise date for Tepe Giyan VC, but they are all behind paywalls. I will assume the date displayed on the Louvre's page is the most accurate estimate for this artifact.

***

The book Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] is a catalog of ancient seals and stamps from the "Near East", dating from the late Aceramic Neolithic to early Bronze Age, in the collection of Lenny Wolfe and family.

Figure 315 in Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] is described as: "cross with arched "hands" ending in triangles pointing to center and ending in small, curved line. Swastika formed from bull heads(?) First half or middle of 4th millennium, later Ubaid period or Gawra/early Uruk period, North Iraq, South-East Anatolia (or West Iran, Giyan horizon?)"

The catalog[108] contains a brief discussion regarding artifacts similar to Amorai-Stark's figure 315:

"the above symmetrical rotating "point group 4mm" design is most typical of later Ubaid glyptic. The swastika motif occurs already in the early Ubaid period but then in a more angular, thinner linear drilling technique. Cf. Von Wickede 1990; 261, Nos, 212 (pendant, Tepe Gawra, early Ubaid period), 242 (round impression, same layout, Tepe Gawra, level XIII, later Ubaid period). [...] For the swastika motif cf. Delaporte 1920: Nos. S.94 (same shape and size, similar design, more angular, careless and without triangular finials, from Susa), G.3 (clay hemispheroid, swastika within circle with tadiating strokes, from Turkey, near Smyrna); Buchanan 1981: No. 24 (not the piece itself but bibliography: Giyan, pl. 38.31 from 11 m.60); Von Wickede 1990: No. 212 (seal-pendant, Tepe Gawra, early Ubaid period); Amorai-Stark 1993: SBF No. 3 (carinated hemispheroid). The exact design of the present hemispheroid is not found on excavated seals."

I was not able to find a copy of von Wickede (1990)[109] or Amorai-Stark (1993).[110] (Amorai-Stark (1993) is not included in the bibliography of the catalog, but presumably it's the work I cite.) Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] cites Buchanan (1981)[111] for his reference to Conteneau and Ghirshman (1935), "pl. 38.31 from 11 m.60".[112] I was unable to find this text online—only a preliminary report by the authors.[113]

There is a photo of this same artifact in the Louvre collections:

Swastika seal from Susa. In the collection of the Louvre Museum, Département des Antiquités orientales. Numéro principal: SB 2539. Numéro catalogue: CCO S. 94. N° de fouille: B 338. Date is not specified, but Delapore (1920)[114] attributes it to the "Époque archaïque".

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010176572

Under figure 379 Amorai-Stark (1997)[108] describes Delaporte (1920)'s[114] figure G.3 as "broken top, swastika within circle, Smyrna, South-West Anatolia". No date is given, so I have not included it here. It may be Bronze Age. In Delaporte (1920),[114] G.3 is on page 96 (description); plate 60, figure 3a, 3b. Delaporte describes the artifact as coming from Collection Gaudin in the Louvre, Inv.: CA 1386. I searched various keywords and was not able to find it in the Louvre's online collection.

Helmand Civilization and related cultures

Swastikas on ceramics have been found at the sites of Shahr-i Sokhta, Khurab, Fanuch (Sistan and Baluchestan province, Iran); Shahi-Tump, Miri Qalat (Balochistan province, Pakistan); and likely others in the Kech-Makran region encompassing parts of eastern Iran and western Pakistan, and southern Afghanistan. This culture is called the Helmand Civilization, which existed in the 3000s-2000s BC.[36] Similar style swastikas have also been found at the Proto-Elamite culture site of Tepe Yahya and possibly an Indus Valley Civilization site, both of which traded with the Helmand Civilization.

Shahr-i Sokhta was one of the most important sites of the Helmand Civilization.[36] Period I of Shahr-i Sokhta dates to ~3550-3000 BC[150] and Shahr-i Sokhta II dates to ~3000-2600 BC.[150]

Radiocarbon dating of an artifact from Period II of the Shahi-Tump site dated to ~3900-3800 BC.[37] However, the Bronze Age period begins a few hundred years later. Miri Qalat is located across a river from Shahi-Tump, and dates to approximately the same time period.[38] It was inhabited from around the 5th millennium BC to the late 3rd millennium (~2000s BC).[152]

Description from Shirazi (2016):[35]

"Fig. 17 – A) Swastika motifs on the Bronze Age pottery of Shahr-i Sokhta, periods I and II (from Sajjadi et al. 2003);[155] B) Swastika motifs on the Bronze Age pottery of Shahi-Tump and Miri Qalat (from Didier and Mutin 2013[154])."

Didier and Mutin (2013)[154] describe the artifacts shown above as belonging to period IIIa, second phase.

Figure 4 in Didier and Mutin (2013),[154] which includes a smaller bowl not shown in the figure from Shirazi (2016).[35] This same figure is published as figure 14.15 in Mutin (2013).[156]

The following is from the abstract of Didier and Mutin (2013).[154] The work was conducted under the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique [French National Centre for Scientific Research], Centre de Recherches Archéologiques Indus-Baluchistan, Asie centrale et orientale - Musée Guimet (UMR-9993). Presumably the artifacts are in the collection of the Musée Guimet, but they do not appear to have a full online collections search.

"This article presents an overview of ceramics found in Pakistani Makran (Southwest Pakistan) during the 4th and the 3rd millennia BC. It is based on recent research conducted by the French Archaeological Mission in Makran (MAFM, CNRS-UMR 9993, MAE), in particular, two PhD dissertations and post-doctoral research on ceramic production in this area."

Excerpt of the description of period IIIa, phase 2, in Didier and Mutin (2013):[154]

"L’assemblage de la deuxième phase de la période IIIa est moins bien connu. Il correspond à la majorité du mobilier funéraire mis au jour par Aurel Stein à Shahi-Tump (d’après ses descriptions et illustrations publiées : 1931, 100, pl. XV-XVI : vases décorés de svastikas), à plusieurs tessons issus de niveaux fortement érodés du chantier IX de Miri Qalat, et à une partie des collections de prospections. Les vases à pâte fine et peints de la deuxième phase sont issus de la même tradition que les céramiques de « Shahi-Tump », mais les formes connues présentent aussi de nouveaux profils et décors7 dont certains préfigurent déjà des composantes de la période IIIb (figure 41-17). Le mobilier de la seconde phase semble davantage distribué dans l’ensemble du Makran et ce, jusqu’à la plaine côtière. Des ratés de cuisson recueillis dans la plaine de Dasht sont les premiers indices de la présence de centres de production dans la région, même s’ils ont probablement existé auparavant. Des parallèles assez nets sont trouvés pour ces céramiques avec des vaisselles produites à partir de la fin du IVe millénaire dans le sud-est de l’Iran, et retrouvées, notamment en contexte funéraire comme à Shahi-Tump, à Shahr-i Sokhta qui est fondé à cette période dans le Séistan (période I : Bonora et al. 2000, p. 505, figure 7; Sajjadi 2003, p. 61, figure 26), ainsi qu’à Tépé Yahya, essentiellement lors de l’occupation proto-élamite (périodes IVC-IVB6: Lamberg-Karlovsky, Potts 2001, p. 76, figure 225B, D; p. 87, figure 37F-I; p. 89, figure 39A-B). Le montage au colombin est dorénavant mentionné sur ces deux sites à cette période (Courty, Roux 1995 ; Laneri, Di Pilato 2000, p. 528-529 ; Vandiver 1986, p. 99-100). Des équivalents sont aussi notés dans la vallée de Bampur à Katukan (Stein 1937, pl. XXXII8/Kat. 018) et Fanuch (collection du Peabody Museum), ainsi qu’au nord de la vallée de la Kech, dans l’oasis de Panjgur (Stein 1931, pl. IIIS.P.1-3, 6, J.D. 9 et 14). Ces comparaisons indiquent que le Makran prend alors part à un réseau de production et de distribution – plus étendu qu’auparavant – d’un même type de céramique vraisemblablement issu de la tradition locale. Les nuances stylistiques observées au Makran, à Tépé Yahya et Shahr-i Sokhta montrent l’existence de variantes sans doute liées à des productions régionales."

"The assemblage of the second phase of period IIIa is less well known. It corresponds to the majority of the funerary furniture unearthed by Aurel Stein at Shahi-Tump (according to his descriptions and illustrations published: 1931, 100, pl. XV-XVI: vases decorated with swastikas), with several shards from levels heavily eroded from Miri Qalat site IX, and part of the prospecting collections. The fine-paste and painted vases of the second phase come from the same tradition as the "Shahi-Tump" ceramics, but the known forms also present new profiles and decorations7, some of which already prefigure components of period IIIb (Figure 41-17). The artefacts from the second phase seem to be more distributed throughout the Makran, up to the coastal plain. Misfires collected from the Dasht Plain are the first clues to the presence of production centers in the region, although they probably existed before. Fairly clear parallels are found for these ceramics with vessels produced from the end of the 4th millennium onwards in southeastern Iran, and found, particularly in funerary contexts such as at Shahi-Tump, at Shahr-i Sokhta which was founded during this period in Seistan (period I: Bonora et al. 2000, p. 505, figure 7; Sajjadi 2003, p. 61, figure 26), as well as in Tépé Yahya, essentially during the Proto-Elamite (periods IVC-IVB6: Lamberg-Karlovsky, Potts 2001, p. 76, figure 225B, D; p. 87, figure 37F-I; p 89, Figure 39A-B). Coil mounting is now mentioned on these two sites during this period (Courty, Roux 1995; Laneri, Di Pilato 2000, p. 528-529; Vandiver 1986, p. 99-100). Equivalents are also noted in the Bampur valley at Katukan (Stein 1937, pl. XXXII8/Kat. 018) and Fanuch (collection of the Peabody Museum), as well as north of the Kech valley, in the oasis of Panjgur (Stein 1931, pl. IIIS.P.1-3, 6, J.D. 9 and 14). These comparisons indicate that the Makran then took part in a production and distribution network – more extensive than before – of the same type of ceramics, probably from the local tradition. The stylistic nuances observed in Makran, Tépé Yahya and Shahr-i Sokhta show the existence of variants undoubtedly linked to regional productions."

In Mutin et al. (2017),[151] the authors describe this style of pottery as being produced until the mid-3rd millennium, and state generally that the artifacts discussed date to "ca 3000 BC":

"It is now established that this ceramic, whose name was given more recently (Mutin 2013a:[156] 264-267), dates to ca 3300/3200-2900/2800 BC.

[...]

The types of fine ceramics considered in this article date more specifically to ca 3000 BC. They are termed in Kech-Makran Late Shahi-Tump ware and characterize Late Period IIIa in this region (Mutin 2013a:[156] 264-270 and 2013b:[157] 32-34). They include some of the vessels that Wright incorporated in EGW [Emir Grey Ware], particularly some of her Type 1, the only type chronologically consistent with LST [Late Shahi-Tump ware] (Wright 1984:[158] 125-131), and additional materials dating to ca 3000 BC we identified in the collections from Tepe Yahya, Shahr-i Sokhta, and Iranian Balochistan (Mutin 2013b:[157] 32-34, 88-90, 354: figs. 3.36-3.37, 355: fig. 3.38, 357: fig. 3.40 and 358: fig. 3.41)."

Mutin (2013)[156] describes period IIIa in more detail:

"Period IIIa in the Pakistani Makran is also called the "Shahi-Tump Graveyard Culture" after the funerary materials first excavated by Stein (1931: 88-103)[162] at Shahi-Tump. The chronological position of this period, posterior to Period II, has been set by Besenval (2005: 4-6).[175] Stratigraphic evidence and stylistic differences observed among the ceramic vessel types has then led us to envisage two main phases for Period IIIa: the first one starting around the middle of the fourth millennium BC, while the second ranging from the late fourth millennium BC to c. 2900/2800 BC.10

[...]

In Pakistani Makran, the ceramic vessels produced during the second phase of Period IIIa include a fine, painted ware linked to early Shahi-Tump ware, although several changes can be noted in terms of profiles and decoration (Fig. 14.15/1-14.15/17). The materials of this phase correspond to most of the funerary ceramics recovered by Stein (1931: 100)[162] in the south-eastern part of Shahi-Tump. Based on his descriptions and illustrations, it is clear that most of these vessels show significant differences compared to the ceramics found by the French mission at the same site farther to the north-west in Trench II. Stein's bowls are, for example, mostly decorated using the swastika motif (Stein 1931: pls. XV-XVI).[162] [...] Ceramics that relate to late Shahi-Tump ware were collected by Besenval on other sites in Makran (Mutin 2007),[160] and by Stein (1931:[162] pl. l.III, J.D.9, J.D.14, S.P.1, S.P.6) in the Panjgur Oasis, located north of the Kech Valley; in the Bampur Valley at Katukan; and at Fanuch (identified in the collection of the PMAE [Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University]; Fig. 14.16/6-14.16/9). Also located in the Bampur Valley, Khurab provided a few comparative examples, including two sherds collected on the surface (Fig. 14.16/11-14.16/12) and two vessels recovered in one burial (Lamberg-Karlovsky and Schmandt-Besserat 1977:[177] 125-30, fig. 6.14-6.15). The swastika painted on one of the Khurab funerary vessel is made using curved lines instead of curved bands usually observed among the Stein assemblage from Shahi-Tump (Fig. 14.16/10). The other materials associated with the collection from Khurab are more recent and this may indicate that the usage of curved lines instead of curved bands for the representation of the swastika corresponds to a later levolution of this type of decoration that is also observed in Makran in Period IIIB (c. 2800-1600 BC; Didier 2007,[178] vol. II: fig. 108).

10. Four calibrated radiocarbon dates from Period IIIa contexts at Miri Qalat are essentially situated within the second half of the fourth millennium BC, with limits at c. 3700 and 2900 BC (Besenval 1997b:[176] 35 n. 50). Recalibration of these dates using OxCal v4.1.7 has provided the same results: Gif-10055 (Period IIIa): 3505-3031 BC (95.4%); Gif-10058 (Period IIIa): 3692-3380 BC (95.4%); Gif-10062 (Period IIIa): 3336-2906 BC (95.4%); and Gif-10059 (originally assigned to Period IIIb): 3483-3031 BC (95.4%)."

The paper Didier and Mutin (2015)[152] gives another overview of Period IIIa of the Kech-Makran region and contains a number of photos of ceramics from the region.

"Period IIIa

Following Period II, Period IIIa is known mostly through graves excavated in the course of Excavations I, II and IV at Shahi-Tump and Excavation IX at Miri Qalat19 (Fig. 11.11), therefore this period is also called Shahi-Tump Cemetery Culture.

[...]

Approximately 20 sites bearing ceramics of Period IIIa were found in Kech-Makran, including sites located near the shoreline. The discovery of a few misfired fragments of Shahi-Tump Ware in the Dasht Plain, approximately 30 to 70 km south of the Kech Valley, points to this area as one of the potential production centres for this type of ceramics. This assumption is also supported by the fact that clay is abundant and pottery workshops from the following Period IIIb were observed in this plain. The presence of Shahi-Tump Ware reported across Kech-Makran, sea-shell objects in the tombs of the Kech Valley, and the presence of sites dating to Period IIIa close to the shoreline show that, likewise during Period II, a regional network of relationships including the coast of the Oman Sea existed in Kech-Makran during Period IIIa. Similarly as for Period II, sherds of Shahi-Tump Ware were found in the Bampur Valley, but a later variety of this style, characterised in particular by bowls with painted swastika motifs (cat. nos. 672–678), is noted as far as at Tepe Yahya and Shahr-i Sokhta at the time of the Proto-Elamite civilization in Iran, in the late 4th and early 3rd millennia BCE. Sherds of Shahi-Tump Ware were found in the Proto-Elamite complex of Tepe Yahya, Period IVC.

[...]

The following Period IIIc is mainly documented for the Miri Qalat Excavation I, in levels that immediately precede an occupation relating to the Indus Valley Civilization.45 Few architectural structures were excavated; the archaeological remains consist mainly of burnt layers filled with ceramic deposits dated by 14C to 2600 to 2500 BCE (Fig. 11.23). [...] The adapted variant of the swastika motif of Period IIIb was replaced by wavy bands associated with leaf motifs.

[...]

The ceramic tradition that emerged in the 4th millennium BCE in Kech-Makran and then became preeminent in the Indo-Iranian borderlands at the end of the 4th millennium and during the 3rd millennium continued to exist during the times of the Indus Civilization, but this period already witnessed its decline. Like in many other areas of Pakistan and Iran, many regions and sites of Baluchistan were abandoned after the Indus Civilization, from about 1900 BCE onwards and during most of the 2nd millennium BCE."

Below is a description of artifacts with swastikas shown in the work.[152]

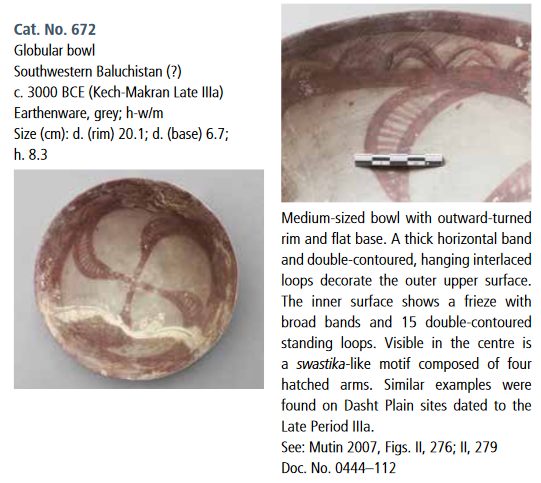

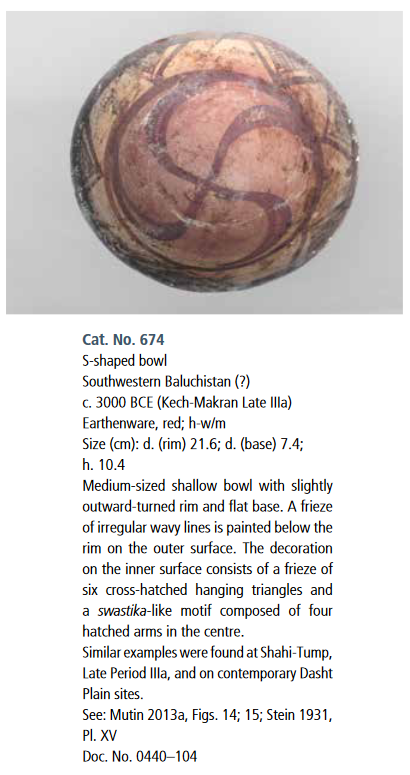

"General Remarks on Cat. Nos. 672–678

Based on stratigraphic and typological analyses as well as stylistic comparisons with ceramics from Iran, it appears that two phases of Period IIIa can be distinguished, one early and one late. The main type of funerary pottery, produced during the second phase of Period IIIa (end of the 4th millennium / early 3rd millennium BCE), is Late Shahi-Tump Ware. It is a very fine-tempered, painted ceramic. It is essentially characterised by hemispherical bowls, decorated with a swastika motif painted on the inner surface. A frieze of geometric motifs such as loops, hatched triangles, and diagonal lines is painted along the rim on the periphery of the swastika motif (Mutin 2013a,[156] 264–267). Cat. nos. 672–678 have swastikas with four branches. However, the ceramic assemblages collected by Sir A. Stein at Shahi-Tump (Stein 1931,[162] 100 Pls. XV–XVI), by the French Archaeological Mission at Miri Qalat Trench IX (Levels VI–II), and on the surface of additional sites in Kech-Makran also include vessels decorated with swastikas with three to six branches (Mutin 2007,[160] 2013a[156]). [...] Bowls with painted swastikas are also attested in the Parom Basin, located north of the Kech Valley (Stein 1931,[162] Pl. III), and in southeastern Iran in assemblages collected in the Bampur Valley (sites of Katukan, Kanuch, Khurab), at Tepe Yahya Period IVC (Phases IVB6–IVC2), and at Shahr-i Sokhta I (for a detailed comparative study, see Mutin 2013a,[156] 264–267). These strong parallels show that Kech-Makran was part of a vast interaction system during this period. Later variations of the swastika motif design are observed in Kech-Makran Period IIIb (c. 2800–2600 BCE); it is made with curved lines instead of curved bands such as on cat. nos. 690–691 or using palm motifs such as on cat. nos. 680–681 (Mutin 2013a,[156] 266; see Didier 2013,[163] 103 Figs. 64; 68)."

(Note, the attribution of swastikas to Stein (1931),[162] pl. III must be a typo, as no swastikas seem to be present in that plate.)

The artifacts below were seized from an illegal collection in Pakistan in 2005. They are now in the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan.[179]

Photo of Helmand Civilization ceramic from Didier and Mutin (2015).[152] Globular bowl, possibly from southwestern Baluchistan, c. 3000 BC (Kech-Makran Late IIIa). In the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan, Catalog Number 672, Doc. No. 0444–112. "See: Mutin 2007,[160] Figs. II, 276; II, 279."

Photo of Helmand Civilization ceramic from Didier and Mutin (2015).[152] Conical bowl, possibly from southwestern Baluchistan, c. 3000 BC (Kech-Makran Late IIIa). In the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan, Catalog Number 673, Doc. No. 0445–107. "See: Mutin 2007,[160] Fig. II, 284."

Photo of Helmand Civilization ceramic from Didier and Mutin (2015).[152] S-shaped bowl, possibly from southwestern Baluchistan, c. 3000 BC (Kech-Makran Late IIIa). In the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan, Catalog Number 674, Doc. No. 0440–104. "See: Mutin 2013a,[156] Figs. 14; 15; Stein 1931,[162] Pl. XV."

Photo of Helmand Civilization ceramic from Didier and Mutin (2015).[152] Globular bowl, possibly from southwestern Baluchistan, c. 3000 BC (Kech-Makran Late IIIa). In the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan, Catalog Number 675, Doc. No. 0442–110. "See: Mutin 2013a,[156] Figs. 14; 15; Stein 1931,[162] Pl. XV."

Photo of Helmand Civilization ceramic from Didier and Mutin (2015).[152] Globular bowl, possibly from southwestern Baluchistan, c. 3000 BC (Kech-Makran Late IIIa). In the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan, Catalog Number 676, Doc. No. 0441–111. "See: Mutin 2013a,[156] Figs. 14; 15."

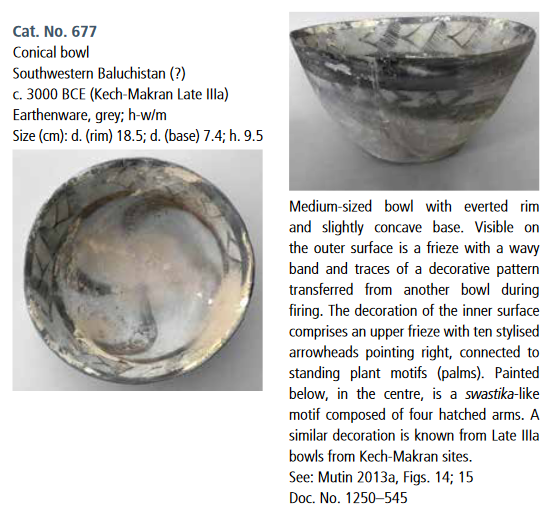

Photo of Helmand Civilization ceramic from Didier and Mutin (2015).[152] Conical bowl, possibly from southwestern Baluchistan, c. 3000 BC (Kech-Makran Late IIIa). In the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan, Catalog Number 677, Doc. No. 1250–545. "See: Mutin 2013a,[156] Figs. 14; 15."

Photo of Helmand Civilization ceramic from Didier and Mutin (2015).[152] Conical bowl, possibly from southwestern Baluchistan, c. 3000 BC (Kech-Makran Late IIIa). In the collection of the National Museum of Pakistan, Catalog Number 678, Doc. No. 0754–160. "See: Didier 2013,[163] Figs. 80; 83."

Figure 14.16 (10) from Mutin (2013).[156] Ceramic from Khurab, Makran. Description: "Figure 14.16. Late Shahi-Tump ware-related vessels ... Vessel no. 10 is probably more recent."

Figure 2 in Mutin et al. (2017).[151] Description:

"Selection of shallow bowls of LST [Late Shahi-Tump ware]. 1-3) Kech-Makran, site 24, Dasht Plain (© French Archaeological Mission in Makran); 4) Shahr-i Sokhta (Piperno and Salvatori 2007:[159] Fig. 773); 5) Shahr-i Sokhta (Sajjadi 2003:[155] Fig. 26); 6) Shahr-i Sokhta (Piperno and Salvatori 2007:[159] Fig. 609); 7) Miri Qalat (Mutin 2007:[160] Fig. 2.224); 8-10) Shahi-Tump (Mutin 2007:[160] Fig. 2.212); 11) Tepe Yahya (Potts 2001:[161] Fig. 2.25 D); 12) Tepe Yahya (Potts 2001:[161] Fig. 1.6 K)."

***

Having catalog numbers specified in the texts would make it so much easier to cross-reference and determine how many unique artifacts are actually shown across all of these republished figures! Below are a few of the older excavations in the region, which contain more annotation of the artifacts.

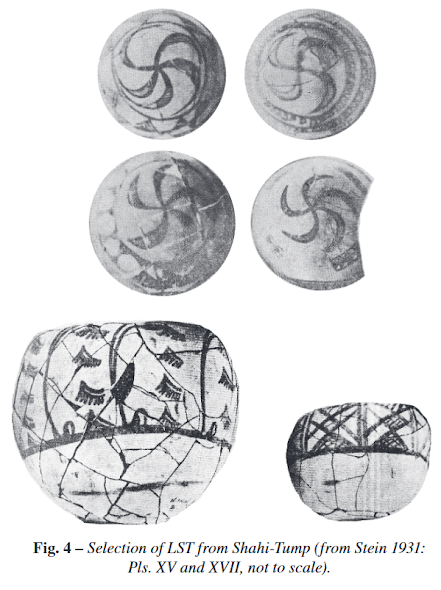

Figure 4 in Mutin et al. (2017).[151] Description: "Selection of LST [Late Shahi-Tump ware] from Shahi-Tump (from Stein 1931:[162] Pls. XV and XVII, not to scale)."

Plate XV, Sh.T.vii.13.d, as it appears in Stein (1931).[162] Description: "Funeral pottery from Shāhī-Tump mound, Kēj valley, Makrān."

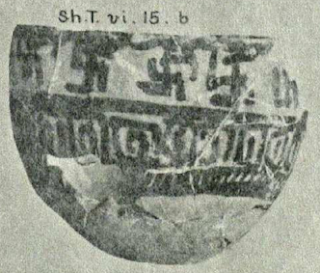

Stein (1931),[162] plate XVI, Sh.T.vi.13.f. The image quality is not high enough to tell if it's a four-armed swastika, or possibly a five-armed spiral. Description: "Funeral pottery from Shāhī-Tump mound, Kēj valley, Makrān."

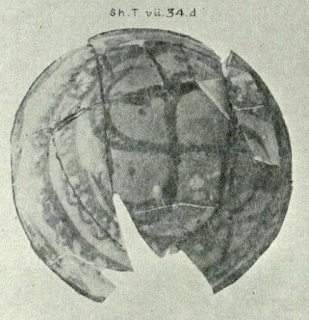

Stein (1931),[162] plate XVI, Sh.T.vii.34.d. Description: "Funeral pottery from Shāhī-Tump mound, Kēj valley, Makrān."