This article is part of a series examining the use of the swastika worldwide.

There are many different blogs and websites which bring attention to swastikas in Africa and other regions throughout the world. However, quite frankly, none of them succeed in capturing their full variety and range. We have attempted to compile and document all this information in one place. Roman-era swastikas in North Africa will be posted on a separate page.

The oldest known swastikas in Africa appear in Egypt by 2000 BC. During the Roman and Christian period of Egypt, swastikas became tremendously widespread within Egypt, and by this time period they traveled south along the Nile River Basin into Sudan and Ethiopia.

From there, the swastika may have continued traveling southward into Tanzania, or it my have arisen there independently. Our knowledge of the swastika's use by the indigenous inhabitants of Tanzania is scarce. The use of swastikas in modern Tanzania seems to have been largely influenced by immigrants from the Indosphere, who brought the swastika with them.

Independently, the swastika became prevalent in western Africa (including the nations of Ghana, Ivory Coast, Togo, Nigeria, Mali, and Burkina Faso), perhaps as early as the 1200s-1400s AD. Swastikas may have been used here even further back, but archaeological evidence is too scarce to allow us to come to a conclusion.

The swastika is also found in the lower part of the Congo River Basin, among certain cultures who speak languages belonging to the Kongo language group, in addition to the Kuba culture who live near the central part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Could the swastika have diffused from western Africa into the Congo Basin?

Much remains unknown about the swastika's use and history in these regions. If you have any additional information, please share it on this article's discussion page:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/2020/10/african-swastikas.html

With this project, we will once and for all demonstrate that the swastika is a world-wide symbol to which Neo-Nazis and other tribalists have no claim.

Map showing the approximate locations of the cultures and artifacts mentioned in the article. (Mediterranean countries not shown on the map will be examined in a future article, given their historic association with the Mediterranean and Roman cultural sphere.)

To return to the index of swastika articles, click here:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/the-swastika-aryan-symbol.html

Table of Contents

- 1. Western Sahel region; central Africa

- 2. Egyptosphere; eastern Africa

- 3. Southern Africa

- 4. Egyptian Revival Art

- 5. Other Symbols

- 5. Index of Names and Meanings of the Swastika

- Footnotes

1. Western Sahel region; central Africa

Ghana

Akan culture gold weights (mrammou)

Weights made of brass used to measure gold dust. Also commonly referred to as Ashanti goldweights. (The Ashanti are a subgroup of the Akan culture). The weights began to be used around 1200-1400 AD. Simple geometric symbols predominated in the earliest periods, with complex weights made in the shape of humans, animals, etc. becoming common around 1600-1700 AD.

Description: "Akan goldweights from the Institute of African Studies Museum at the University of Ghana, Legon." Photo by Flickr user imknowmadic2.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/imknowmadic2/3133679624/in/album-72157601513834603/

Description: "Akan goldweights from the Institute of African Studies Museum at the University of Ghana, Legon. Here they are grouped under the category "Fihankra", which is the Akan word referring to the square courtyard enclosed by four adjoined buildings." Photo by Flickr user imknowmadic2.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/imknowmadic2/3132858789/in/album-72157601513834603/

Swastikas and symbols referred to as "Nsaa". Photo by Flickr user imknowmadic2.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/imknowmadic2/2657942301/in/album-72157601513834603/

Goldweights from Kumasi, Ghana. Looted by British Captain Eden during the Anglo-Ashanti war in 1874. (First published in Ilios, by Heinrich Schliemann (1880), page 353. Figure republished in The Swastika, the Earliest Known Symbol, by Thomas Wilson (1896), as figure 138, page 838.)

***

There are numerous additional examples of goldweights with swastikas on them. Here are a few.

Object number AM-586-57 in the collection of the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal, Netherlands.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/531172

Object number AM-586-76 in the collection of the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal, Netherlands.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/531212

Object number AM-651-8 in the collection of the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal, Netherlands.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/533113

Accession number 75.31.35 in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, USA.

https://art.famsf.org/goldweight-swastika-shape-753135

Accession number 75.31.32 in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, USA.

https://art.famsf.org/goldweight-swastika-shape-753132

Nkontim symbol

The Nkontim is one of the Adinkra symbols, used Ghanaian fabrics, pottery, and designs. It is a swastika with spiraling or curved arms, which is a separate form from the swastikas on the goldweights with sharp 90 degree angles. It is also referred to as Nkotimsefuopua[1] or Nkotimsefoc pua.[2]

It is said to be named after the hairstyle of the Queen Mother's attendants,[1] and have a meaning of "loyalty and service."[3]

According to Wikipedia, the Adinkra symbols were designed or compiled by King Kwadwo Agyeman, ruler of Gyaaman from 1850-1895, and the symbols are most strongly associated with the Bono/Abron culture (a subgroup of the Akan). However, there are examples of textiles with the Nkontim (swastika) symbol from 1817 and 1825, so the symbol predates King Kwadwo Agyeman's compilation or standardization of the symbols.

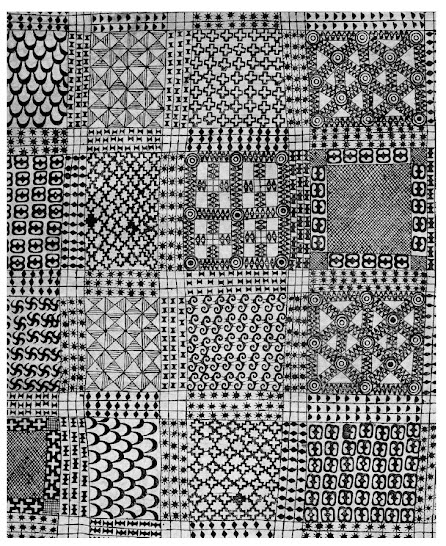

Adinkra cloth collected in 1817. According to the museum's description, it was made by the Dagomba culture, who live in northern Ghana and are not part of the Akan ethnic group. In the collection of the British Museum, London, UK. Museum number and registration number Af1818,1114.23.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Adinkra_cloth.JPG

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Af1818-1114-23

Cloth obtained by the Dutch in 1825. According to the museum's description, it was likely made for Dutch King William I, as it has the Dutch coat of arms in the center. Object number RV-360-1700 in the collection of the Museum Volkenkunde (National Museum of Ethnology) in Leiden, Netherlands.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Adinkra_1825.jpg

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/605114

Description: "This cloth was worn by King Agyeman Prempeh I [of the Ashanti Empire] on the day the British deposed him in January 1896." In the collection of the National Museum of African Art - Smithsonian Institution. Object number: 83-3-8, Unique Media Name: NMAfA-S20050019-000001.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmafa_83-3-8

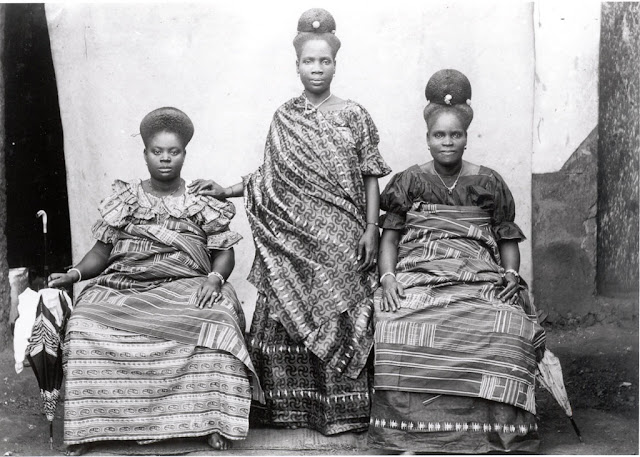

Fante (Fanti) culture women of the Ghana region, ca. 1910. Photo from the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art - Smithsonian Institution. Identifier: EEPA.1995-018, Item EEPA 1995-180067.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/imknowmadic2/3235071868/

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/ead_component:sova-eepa-1995-018-ref574

Wooden Nkontim stamp, pre-1957. Object number TM-2667-1 in the collection of the Tropenmuseum (Museum of the Tropics) in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/86395

Nkontim on a woman's headscarf in Ghana, 2005. Photo by Retlaw Snellac Photography (Flickr username waltercallens).

https://www.flickr.com/photos/waltercallens/394150296

Image reposted on the blog "selfuni" with the caption "Comb, Akan people, Ghana". Date and original source unknown.

https://selfuni.wordpress.com/tag/african-swastika/

***

Lastly, here is another swastika-like Adinkra symbol. After briefly searching through some online guides for Adinkra symbols, I haven't been able to find its name.

Panel from a Ghanaian cloth, pre-1975. Object number TM-4254-5 in the collection of the Tropenmuseum (Museum of the Tropics) in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/135802

Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire)

Poids Baoulé (Baoulé weights)

Although the most common examples seem to be from Ghana, similar swastika-bearing goldweights were historically used in the surrounding regions where Akan culture had an influence. For example, the Baoulé (Baule) people in the nation of Ivory Coast have "Poids Baoulé" (Baoulé weights).

Baoulé weights shown in "a temporary exhibit in September 2016 at Place Donwahi," Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

https://web.archive.org/web/20201024235715/http://www.proswastika.org/news.php?extend.714.3

Theodore Monod attempted to trace the development of the swastika in Baule weight motifs. He argued the swastika developed from a simplification of comb-like motifs.

It seems, at all events, feasible to recognize for the Baule region of the Ivory Coast, French West Africa, all the stages of the local (and probably autochthonous) development of a geometrical pattern ranging from the simple one-sided comb (Nos. 1-2) to the most typical swastika (Nos. 36-37), the latter being possibly nothing more than a purely ornamental design.

The specimens represented in Plate E are from the collection of Baule weights in the Institut Frangais d’Afrique Noire, Dakar.

I describe hereafter the stages likely to be admitted between the one-sided comb and the swastika, with simple arms.

[...]

We are also reminded, once more, that characteristic, and even somewhat complex forms, may sometimes have separate origins, their final identity only due to mere convergence.

If the West African swastika is actually autochthonous, one may well ask whether still others, e.g. the American or the Chinese, will not also prove to be of local growth.[4]

Togo

Nkontim symbol

It appears that Adinkra and Nkontim symbols can also be found on Togolese fabrics. I'm not sure what these symbols are called in the local language.

The location of the following image was not given. It is possible it's in the south of Togo. The Ewe language, commonly spoken in southern Togo, is part of the proposed Kwa language family (along with the Akan, Bono/Abron, Fanti, and Baoulé languages--whose speakers also use the swastika).

Photo taken by Wikipedia user Alexander Sarlay, 2016. Unspecified location in Togo.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Afrikanische_Textilien.jpg

"Textilhändlerin präsentiert ihre bunten Stoffe in Togo."

"Textile retailer presents her colourful fabrics in Togo."

Guin (Mina) culture clothing

Another variant of swastika from Togo.

Photo reposted on the website SvastiCross in 2014. Women at the Epé-Ekpé festival in Glidji, Togo.

https://svasticross.blogspot.com/2014/05/swastika-togo.html

According to the Flickr user TRANSAFRICA TOGO:

"Every year in the village of Glidji, 30 miles from Togo's capital city of Lome, members of the Guen tribe gather together for the Epe Ekpe festival -- part family reunion, part New Year's Eve, part religious worship."

https://www.flickr.com/photos/transafrica-togo/albums/72157646949055033/

Further explained by a Google translation of a UNESCO World Heritage Convention article about this region:

"The Aného-Glidji agglomeration constitutes two historic cities, Aného, the economic capital of the Guin country and Glidji, the spiritual heart. This complex is the result of a history that spans three centuries and which has allowed the emergence of an atypical urban civilization, testifying to a considerable exchange of influence (18th-19th-20th centuries) between indigenous populations. Xla-Xweda and waves of immigrants from present-day Ghana as well as reflux Afro-Brazilian populations, European traders and administrators and their mestizos.

[...]

The authenticity of the site lies in the presence and the durability of numerous sanctuaries of the guinyéhoué (most often deified ancestors), of the Aja voodoo forming a particular pantheon. In this pantheon, gods of various origins coexist: those brought back from Accra and El Mina, those of Adja roots, found on the spot, and even captive slaves.

Among the attributes of these living cities we note the celebration each year of the new year guin or Epé-Ekpé which brings together all the natives of the living environment in Togo or in neighboring countries (Benin, Ghana and the diaspora)."

https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6601

The Guin language (or Gen, Mina, Gen-Mina, among other names) is also classified as part of the Kwa language family.

Nigeria

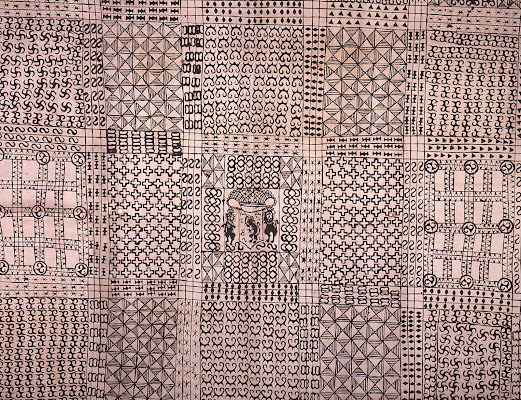

Yoruba culture Adire textiles

According to Wikipedia, the popularity of Adire dyed fabrics reached its peak from 1900 to the 1930s and continues to be common today.

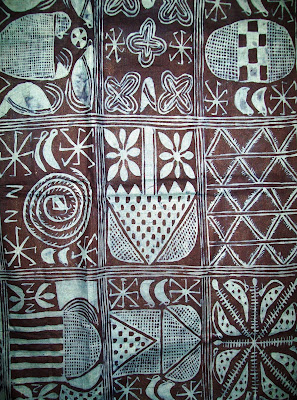

Adire textile from Ibadan, Nigeria, with small swastikas surrounding a coiled snake, ca. 1960-1964. In the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK. Accession number: CIRC.588-1965. Image 12 of 41.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/

A number of the other panels from this same cloth also have swastikas. In the image above, they have been merged together for convenient viewing (click to see full size).

See images 6, 12, 19, 20, 21, 27, and 28 to see the panels with swastikas.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GK1241

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GK1247

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GK1254

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GK1255

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GK1256

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GK1262

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GK1263

Additionally, images 7, 22, 24, 26, 30, 33, 34, 39, and 40 show parts of neighboring panels, where swastikas are visible.

***

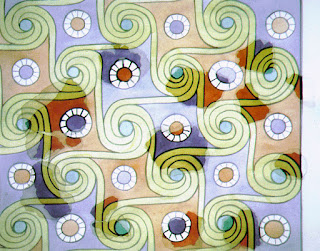

Adire cloth with four connected whirls which has some similarity to a swastika. I do not know if this is merely a decorative pattern or if it has some cultural meaning. Judging by the vast array of designs on adire cloth, I suspect this is decorative and not an intentional swastika. Collection, date, and origin unknown.

Yoruba(?) culture gourd bowl

In 1897 anthropologist Felix von Luschan published a book which included many artifacts displayed at a German colonial exhibition. In the book, he published an illustration shown to him by British anthropologist Henry Balfour. Although the precise culture and origin of the artifact was unknown to von Luschan, he believed it to be from the Yoruba culture. The Yoruba people live primarily in Nigeria, although they extend as far west as Ivory Coast.

For more discussion on this artifact, see von Luschan's writing, republished here.

Mali and Burkina Faso

Bògòlanfini (Bogolan) textile

According to Wikipedia, Bògòlanfini (Bogolan) is a style of cloth strongly associated with Malian culture. From what I can tell, it seems to be common in Burkina Faso as well.

The image above is Bogolan-style textile sold by the French company Africouleur. I do not know if the following swastika is based on an authentic pattern, or if it is just made up by Western companies. The four triangles arranged in a spiral pattern is likely an authentic pattern (see the "Other" section at the bottom of this page for a few examples of this motif in other cultures).

Translation of the Africouleur company's website to show it is designed by the company, rather than an authentic/imported piece:

"At Africouleur, you'll find custom-made African fabric curtains, whose colours and ethnic patterns will embellish your home. Our African-patterned curtains are made to your liking, with the splendid and very thick bogolans of Mali, in very chic and lighter hand-tinted bazins or trendy wax loincloths. And we offer transparent veils in hand-tinted Benin cotton veils."

https://www.africouleur.com/boutique/decoration-africaine/rideaux/rideaux-voilages/

A very similar pattern on a t-shirt, labelled as a "Bogolan Loincloth from Mali", is being sold by the brand MamySor. As far as I can tell, this brand is owned/operated from Burkina Faso or Ivory Coast, so perhaps this is indeed an authentic motif from this region.

https://fashionomicsafrica.org/en/marketplace/175-239-bogolan-t-shirt.html

This motif is also sold on products made by the French company Afro Craft, whose owner apparently collaborates with residents of Burkina Faso. Who can resist obtaining matching shirt and pants with this pattern?

http://www.afro-craft.com/objets-africains/pantalon-africain/pantalon-bogolan/pantalon-bogolan_p21082_f58.aspx

http://www.afro-craft.com/objets-africains/vestes-bogolan/veste-bogolan_p21118_f61.aspx

Bogolan cloth sold by the Italian company Etnic Art, claimed to originate from Africa.

https://www.etnicart.it/en/original-african-bogolan-painting-bogolan3.html

Another example of this pattern, claimed to be from Mali. Uploaded by a Pinterest user without any source. I am unable to find further information.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/298645019039665337/

Democratic Republic of the Congo

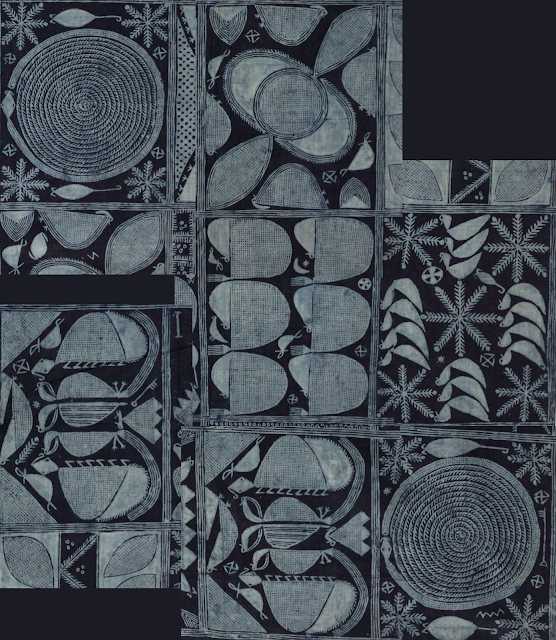

Kuba culture textiles

Kuba textiles characteristically have a vast variety of geometric shapes and are notable for their often irregular patterns. The swastikas on the following textiles might therefore be a coincidence rather than a widespread symbol.

Kuba raffia cloth from the Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire). Item number #c003 in the collection of Faru Imports Unlimited, Charlotte, North Carolina. Date unknown. It is notable that it occurs next to a triskelion and the cross-like symbol with four squares in the corners with one overlapping in the center (called "Nsaa" in the Ghanaian Adinkra symbols), which also appears near the swastika in some Akan weights and in non-African cultures as well.

https://web.archive.org/web/20081120102146/http://www.faru-faru-faru.com/gallery/c003-4.htm

Kuba raffia textile from the latter part of the 20th century. Item "Hüftrock ncaca 10334" in the collection of Bwoom-Gallery, Wolfenbüttel, Germany.

https://web.archive.org/web/20210807220331/http://www.bwoom-gallery.com/Kuba_Hueftrock_ncaka%20kot_10334.html

The swastika on the far left was clearly designed with careful attention paid to symmetry, however, the irregularity of the other swastika-like forms once again makes us wonder if this is just a coincidence of geometry, rather than a meaningful symbol.

A hand bag labelled as "Kuba Cloth bag" on Pinterest, from a collection of images labeled "Kuba Cloth Decor" on Pinterest. The page has pillow designs, upholstered furniture, framed patterns, and other commercialized products appealing to Western yuppies, so it may be designed by some Western company and not be representative of actual Kuba symbolism. The exact company and origin of the handbag is not listed.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/532409987171869156/

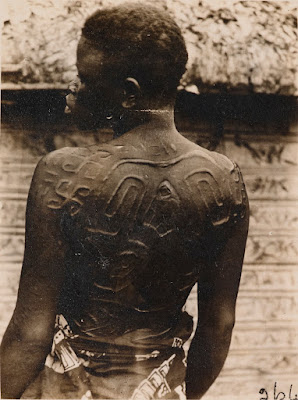

Scarification from the Basundi/Sundi culture

The following image can be found circulating on the internet:

Image text:

"The ancient cross, known as the swastika, scarred upon this woman's back, seems to be sole evidence of Congo negro knowledge of the mystic sign." "Weird Congo Ideals of Adornment by Scarring the Flesh. Photos, Mrs. J. H. Harris".

This image was published in:

Peoples of All Nations, Their Life Today and the Story of their Past, edited by J. A. Hammerton. (ca. 1920). Volume 1: Abyssinia to British Empire, pages 1-784. London: The Amalgamated Press Limited. Page 395.

https://archive.org/stream/PeoplesOfAllNationsTheirLifeTodayAndStoryOfTheirPast_387/Vol1Belgium-BelgianCongo#page/n13/mode/2up

I managed to track down the original photo. It was taken by Alice Seeley Harris, who was married to John Hobbis Harris. (In 19th and 20th century Western naming conventions, it was common to refer to a married woman as Mrs. [husband's name/initials]). Harris's photography documented the barbarity of Belgium's treatment of the inhabitants of the Congo, and her work was influential in forcing King Leopold II to relinquish his personal control of the Congo Free State to the "oversight" of the Belgian government.

The University of Nottingham's Antislavery Usable Past project collaborated with the organization Antislavery International to upload a collection of hundreds of Harris's photos online in the Alice Seeley Harris Archive:

http://antislavery.nottingham.ac.uk/solr-search?facet=collection%3A%22Alice+Seeley+Harris+Archive%22

Photo Archival Number "MSS. Brit. Emp. S. 17 / B15 (Box 15/1)" in the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, UK. Digital item number 1124 in the University of Nottingham's Antislavery Usable Past project.

http://antislavery.nottingham.ac.uk/items/show/1124

Here is the original photo. The caption on the photo says it was taken in the "Mayumbe Country" during 1911-1912. "Cicatricing" is a term to refer to the process of scarification by burning, a practice which seems to have taken place throughout much of Africa during this time period.[5] To see the caption and a larger version of the image, see the link above.

This appears to be the same photo, mirrored. For a larger version, see the link below. Digital item number 2074 in the University of Nottingham's Antislavery Usable Past project.

http://antislavery.nottingham.ac.uk/items/show/2074

The precise location of the photo is not stated. However, it was presumably taken along the Mayumbe line, a railroad extending from Boma to Tshela. The photos tagged with Mayumbe in her collection include a photo taken of the Lukula rail station, which is on this route.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayumbe_line

http://antislavery.nottingham.ac.uk/items/show/1261

***

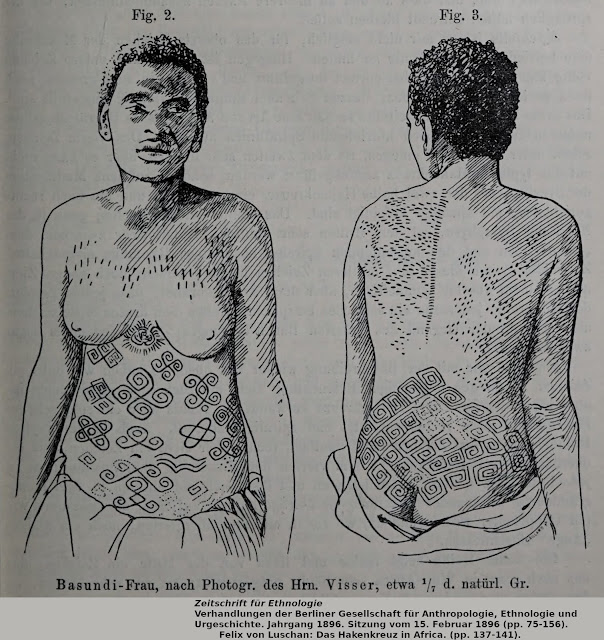

Similar scarification was observed in the Basundi/Sundi culture of the western area of Congo during the same timeframe. I assume this is the same culture as Harris's photo, or a closely related one. The Kongo language and Kongo cultures (which includes the Sundi/Basundi) span over the region near the mouth of the Congo River.

Drawing of a photo taken by Robert Visser, published by Felix von Luschan in 1896. I have not found Visser's original photo, but perhaps a collection of his work would have more information as to the precise location, etc. of this photo. (For more information on this image, see von Luschan's work, republished here.)

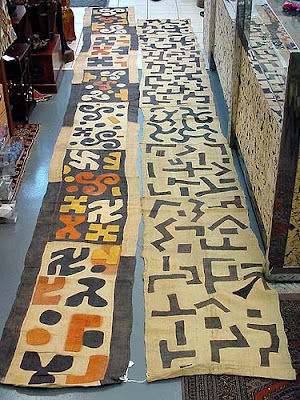

Textile said to be from Congo

This textile is said to be from Congo, although the precise culture it originated from and other information were not specified.

"In the traditional beliefs of the ancient Kingdom of Congo, the diamond-shaped swastika is also a sacred symbol. Mr. Marc Leo FELIX, a collector of Congolese artifacts, said: "The swastika represents the four important moments of life: birth, maturity, death, and rebirth. The upper half is the human world, and the lower half represents the spiritual world. It is a view of the reincarnation of the soul."

https://web.archive.org/web/20090425072627/http://www.epochtimes.com/b5/9/4/22/n2502980.htm

2. Egyptosphere; eastern Africa

Egypt

Ancient Egyptian swastikas

According to research by Thomas Wilson (1896), at the time there were no known "pre-Christian" swastikas documented in use by the natives in Egypt, despite the Neolithic period in Egypt having been genetically and culturally influenced by Neolithic farmers from Fertile Crescent cultures who likely used the swastika.

After our research research into the world's oldest swastikas, we were able to compile a number of them from ancient Egypt dating back to at least 2000 BC. For more detailed information on the swastika's use in ancient Egypt, refer to the article below:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/worlds-oldest-swastikas.html#AncientEgypt

The image above is commonly circulated on the internet as an example of an ancient Egyptian swastika. The caption on the website which uploaded the image said: "Fig. 8 – Carvings on a stone, (Egypt) / IV- III millennium."

https://web.archive.org/web/20110204191934/http://www.archaeometry.org/swastika.htm

After further research I came across the original photo of this rock carving (above). It is from the Dakhla Oasis and dated by Hans Alexander Winkler to the Dynastic Period, ca. ~2500-332 BC.

https://archive.org/details/rockdrawingsofso0002wink/page/58/mode/2up

Swastika on the trail to Abu Ballas. Fig. 35 in a research paper by Frank Förster (2007). Description: "Rock engravings at ‘Muhattah Harding King’ (site Jaqub 99/35, photo: R. Kuper)."

https://www.academia.edu/2222292/F%C3%B6rster_F_2007_With_donkeys_jars_and_water_bags_into_the_Libyan_Desert_the_Abu_Ballas_Trail_in_the_late_Old_Kingdom_First_Intermediate_Period

Swastika-like seals. Figures 546-556 in plate 27 of André Wiese (1996). In figure 555 we can see a sloppy swastika, and in figure 556 we can see a "true" swastika. Figure 555 and 556 date to roughly 2180-2055 BC.

https://archive.org/details/Wiese1996DieAnfaengeDerAegyptischenStempelsiegelAmulettePages4389/mode/2up

Seal with a swastika inside of a labyrinth. Figure 1260 in plate 61 of André Wiese (1996). Seal dates to roughly 2180-2055 BC.

For further information references on the artifacts listed above, see:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/worlds-oldest-swastikas.html#AncientEgypt

***

In addition to the artifacts above, there are a few other examples of swastikas from ancient Egypt, but detailed information regarding the artifacts' locations and so forth are not known.

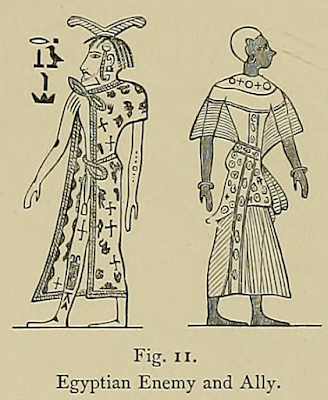

Non-Egyptian and Egyptian said to be from a mural from the era of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BC). I have not been able to find the original mural. Based on other depictions in ancient Egyptian art, the headwear of the man on the left suggests he is a Libyan.

Image published in:

Marian Alford. (1886). Needlework as Art. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. Figure 11, page 104.

https://archive.org/details/needleworkasart00alfo/page/104/mode/2up

Two examples of swastika frets in ceiling decorations from the Theban Necropolis, dating from the 17th to 20th Dynasties. The precise tomb it's from is unknown. The 17th Dynasty began around 1580 BC and the 20th Dynasty extended to around 1077 BC. The one on the left is illustrated in Fig. 25 in The Swastika, by Thomas Wilson (1896).

Illustration first published in:

Émile Prisse d'Avennes. (1878). Histoire de l'art égyptien d'après les monuments: depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'a la domination romaine. Tome Premier: Architecture. Paris: Arthus Bertrand, Éditeur.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7300477j/f42.vertical

The plate is titled "Ornementation des Plafonds: Guillochis & Méandres (Nécropole de Thèbes -- XVIIe. à XXe. Dyn.)". It is on page 42/81 (pdf numbering) of the BnF Gallica link above. A high resolution scan by the New York Public Library Digital Collections is linked below.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-685e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

It appears in 1879 the next volume was published, consisting of text written by Pierre Marchandon de La Faye. It may have text further describing the Necropolis.

https://archive.org/details/39020025953889-histoiredelarte/page/n7/mode/2up

***

A previous version of this article speculated that the following image, said to be "Egyptian seals of the Eighth Dynasty showing labyrinthine patterns", might contain a swastika:

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEijghMQWPWAlaM3GD02wiC46N5kpcCjYLDxHozVK-Wau7APBwvPRO_0rCnJSn41xTTCPs-HGImbN4xMeFEksb6ISneA8A3wF5qb9XkNfnWMdZmIyLgtulkdht_1D9EYie5UhazN_zVsdF4/s0/Egyptian_Seals.png

https://web.archive.org/web/20071010013614/http://www.math.nus.edu.sg/aslaksen/gem-projects/maa/Interview_with_the_Minotaur/rite.htm

However, a higher-resolution tracing of this artifact reveals it is not. See figure 1247 in Wiese (1996):

https://archive.org/details/Wiese1996DieAnfaengeDerAegyptischenStempelsiegelAmulettePages4389/page/n337/mode/2up

Ancient Greek pottery found in Egypt

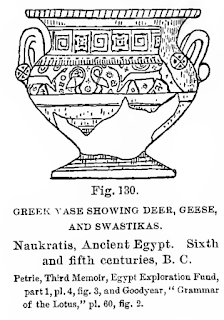

The city of Naukratis (Naucratis) was a Greek village in the Nile Delta. Archaeologist Flinders Petrie was among those to excavate the site. Thomas Wilson (1896) republished a number of images from Petrie showing Greek pottery found in this city, dating from approximately 600-400 B.C.

In other words, the swastikas below are not culturally Egyptian. However, it is another example of the swastika being physically present in Egypt in ancient times.

Description: "Greek vase showing deer, geese, and swastikas. Naukratis, Ancient Egypt. Sixth and fifth centuries, B.C."

***

The British Museum in London, UK, has dozens of examples of pottery fragments from Naukratis with swastikas. When searching for "Egypt" and "swastika" they are almost the only result.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=egypt&keyword=swastika

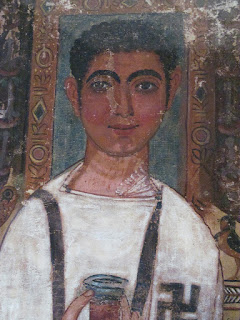

Roman and Christian-era swastikas

In the Roman period of Egypt and later, the swastika was used as a symbol among early Christians. In addition, we can find many more examples of Greco-Roman-style swastika frets from this time period. In total, numerous examples of swastikas in Egypt from this time period can be found.

Egyptian funerary shroud from the Roman period, mid third century AD. Photo taken in the Legion of Honor museum (part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, USA).

https://www.flickr.com/photos/16482030@N00/27299177909

I do not see this artifact in their collections:

https://art.famsf.org/

Another photo. I found this on a Pinterest page which has it as part of a collection called "British Museum Art Images." I don't see it listed in the British Museum's collections search either, so who knows. It is possible this piece was transported to different museums for exhibitions.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/82120393184251998/

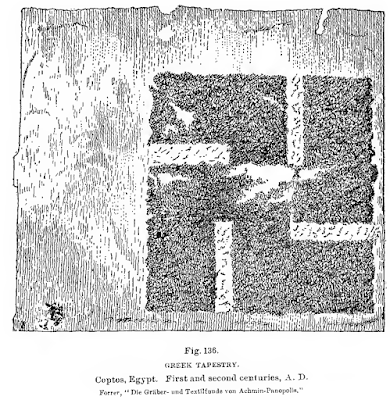

"Greek tapestry. Coptos, Egypt. First and second centuries, A.D." First published in Die Gräber- und Textilfunde von Achmin-Panopolis, by Richard Forrer (1891). Figure republished in Wilson (1896).

Wilson writes: "The inhabitants of Coptos and the surrounding or neighboring cities were Christian Greeks, who migrated from their country during the first centuries of our era and settled in this land of Egypt. Strabo mentions these people and their ability as weavers and embroiderers. Discoveries have been made of their cemeteries, winding sheets, and grave clothes."

This appears to be different from the cloth below.

Egyptian textile, 300s-400s AD, precise location unknown. Click the Wikimedia link to see a much larger version.

In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York City. Accession number 1902-1-20, Object ID 18130409.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Textile_(Egypt),_4th%E2%80%935th_century_(CH_18130409).jpg

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18130409

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:chndm_1902-1-20

***

Cloth found in the grave of Aurelius Colluthus, in the city of Antinoë (Antinoöpolis). Documents found in the grave date to 454, 455, and 456 AD.

Accession number 749-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O354868/tunic/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antino%C3%B6polis

According to the description on the museum's page, the cloth is described in an old book:

Le grand ouvrage de la Commission d'Égypte nous donne une vue des ruines d'Antinoé en 1804. L'ensemble est plein de grandeur: portiques, colonnades, arcs de triomphe. On devine un site archéologique, prêt à dévoiler l'histoire de ses populations.

[...]

De retour au Caire, j'en parlai à M. Albert Gayet, l'égyptologue qui voulut bien se charger de ces explorations, et l'hiver suivant (1896-1897) il se mettait à la besogne.

[...]

M. Gayet avait donc mis la main sur un gisement archéologique de premier ordre, nous révélant quatre civilisations successives embrassant une période de cinq à six siècles. Depuis quatorze ans qu'il y travaille, il a amené au jour les documents les plus importants pour l'histoire, les religions, l'art, les mœurs, et cela avec une telle abondance que tous les musées de l'Europe et de la France en ont été approvisionnés.

[...]

1899-1900

[...]

Enfin M. Gayet avait rapporté le mobilier d'Aurélius Colluthus et de sa femme Tisoia. C'était un document de premier ordre, d'abord par l'abondance des riches étoffes qu'on y a rencontrées et surtout parce qu'on y a recueilli quatre papyrus écrits en grec et dont trois sont datés.

L'un est un contrat de vente. Aurélius donne à sa femme Tisoïa une villa moyennant 9 écus d'or payés comptant: la moitié du puits et la moitié de la cour, qui sont indivis avec sa sœur Taurounia. L'acte est rédigé dans le jargon encombrant qui sert encore aux notaires de nos jours: «...et ceci je le confirme, moi le vendeur et les miens, à toi l'acheteur et aux tiens, par toutes garanties quoi qu'il survienne ou soit survenu, quelque réclamation qu il se produise ou se soit produite, etc...» Date: «l'année après le consulat de Flavius Vincomulius et Opikion, les très illustres, le 6 phaménoth de la septième indiction à Antinoopolis la très illustre» (2 mars 454).

Un certificat de docteur donne la date du 13 février 455, et un fragment de trois lignes, celle du 29 juin 456.

Le morceau important est le testament du défunt. La date était sans doute écrite au début qui manque: «...et fatigué de lutter de mon corps, craignant de quitter la vie subitement et à l'improviste, sain de raison et d'esprit, tenantcomple de tout avec exactitude, valide d'entendement, je fais ce testament sous les yeux de sept témoins que j'ai convoqués selon la loi et qui signeront plus bas à ma suite.. » «...Je veux pour héritier ma chère épouse Tisoïa pour tous les biens que je laisserai, tant meubles qu'immeubles, de tout genre, de toute espèce, de toute valeur... Je veux que mon corps soit enseveli dans un suaire et qu'on célèbre les saintes offrandes et les repas funèbres pour le repos de mon âme devant Dieu tout-puissant...»

C'est un chrétien, mais il parle encore d'offrandes (usage qui a persisté encore dans nos campagnes) et de repas funèbre. Il est question de son co-propriétaire, le très pieux prêtre Chérémon, et un certain Phébammon, fils d'Isidore, sous-diacre, signe comme témoin. Famille cléricale, dirait-on maintenant. Les étoffes aussi sont chrétiennes; deux grands manteaux en tissus frisés avec, à chaque angle, de grands swasticas; de grands suaires multicolores montrant des croix rouges ou vertes et des roses à quatre pétales. Sur les chemises et les robes, aucune ligure, mais des ornements monochromes et géométriques. Enfin, les portraits des défunts; ils ne, sont ni peints sur toile, ni modelés dans le plâtre; c'est un panneau de tapisserie qui nous présente les effigies de Colluthus et de Tisoïa. Hélas! quel art de décadence! ce n'est plus que le procédé technique qui nous rappelle les beaux Gobelins de l'époque romaine. La femme tient un bouquet; le mari porte en mains un papyrus; persistance de l'idée du rituel funéraire qui ouvre les portes de l'au-delà; de même que les portraits mis dans la tombe rappellent les supports du double.

On voit que, moins les soieries, tous les genres de tissus sont fournis par cette trouvaille datée du ve siècle.

Google translate version:

The great work of the Commission of Egypt gives us a view of the ruins of Antinoe in 1804. The whole is full of grandeur: porticoes, colonnades, triumphal arches. We guess an archaeological site, ready to reveal the history of its populations.

[...]

Back in Cairo, I spoke about it to Mr. Albert Gayet, the Egyptologist who was kind enough to take charge of these explorations, and the following winter (1896-1897) he set to work.

[...]

Mr. Gayet had therefore got his hands on a first-rate archaeological site, revealing to us four successive civilizations covering a period of five to six centuries. In the fourteen years that he has worked there, he has brought to light the most important documents for history, religions, art and manners, and that with such abundance that all the museums of Europe and of France were supplied with it.

[...]

1899-1900

[...]

Finally Mr. Gayet had brought back the furniture of Aurélius Colluthus and his wife Tisoia. It was a first-rate document, first of all because of the abundance of rich fabrics found there and above all because four papyri written in Greek were found there, three of which are dated.

One is a sales contract. Aurélius gives his wife Tisoïa a villa for 9 gold crowns paid in cash: half of the well and half of the courtyard, which are undivided with his sister Taurounia. The deed is written in the cumbersome jargon which is still used by notaries today: "...and this I confirm, I the seller and mine, you the buyer and yours, by all guarantees whatever, it arises or has arisen, whatever claim it arises or has arisen, etc..." Date: "the year after the consulate of Flavius Vincomulius and Opikion, the very illustrious, the 6 phamenoth of the seventh indiction in Antinoopolis the very illustrious" (March 2, 454).

A doctor's certificate gives the date February 13, 455, and a fragment of three lines, that of June 29, 456.

The important piece is the will of the deceased. The date was undoubtedly written at the beginning which is missing: "...and tired of struggling with my body, fearing to quit life suddenly and unexpectedly, sane of reason and of mind, taking everything into account with exactitude, valid of understanding, I am making this will under the eyes of seven witnesses whom I have called in accordance with the law and who will sign below after me..." "...I want to inherit my dear wife Tisoïa for all the goods I will leave, both furniture and buildings, of all kinds, of all kinds, of all value... I want my body to be buried in a shroud and that we celebrate the holy offerings and the funeral meals for the rest of my soul before Almighty God..."

He is a Christian, but he still speaks of offerings (a custom which has still persisted in our countryside) and of funeral meals. It is about its co-owner, the very pious priest Cheremon, and a certain Phébammon, son of Isidore, sub-deacon, signs as witness. Clerical family, one would say now. The fabrics are also Christian; two large coats of crimped fabric with large swastikas at each corner; large multicolored shrouds showing red or green crosses and roses with four petals. On shirts and dresses, no Ligurian, but monochrome and geometric ornaments. Finally, the portraits of the deceased; they are neither painted on canvas, nor modeled in plaster; it is a tapestry panel showing us the effigies of Colluthus and Tisoïa. Alas! What art of decadence! It is only the technical process that reminds us of the beautiful Goblins of the Roman era. The woman is holding a bouquet; the husband carries a papyrus in his hand; persistence of the idea of the funeral ritual which opens the doors to the beyond; just as the portraits placed in the tomb recall the supports of the double.

We see that, minus the silks, all kinds of fabrics are provided by this find dating from the fifth century.

Quotation from the following book. The swastika fabric is not illustrated.

Émile Étienne Guimet. (1912). Les Portraits D'Antinoé, Au Musée Guimet. Annales du Musée Guimet, Bibliothèque D'Art. Tome Cinquiéme (Volume 5). Pages 2-3; 10-11.

https://archive.org/details/lesportraitsdant00guim/page/10/mode/2up

This book has another example of swastikas, on the pattern found on a woman's sarcophagus.

La figure 75 nous montre encore les circonférences entre-croisées du filet rouge sur fond vert foncé; les vides sont occupés, tantôt par des swasticas dextres, signe de lumière et d'immortalité, par des fleurs à quatre pétales, par des swasticas senestres, très stylisés, et par des points solaires entourés de petits points stellaires (Pl. XXXVI, D).

[...]

Fig. 75--La tète a une expression de tristesse bien singulière, car tous les autres portraits montrent l'extase de l'au-delà. Cette femme a des bijoux, elle est drapée dans des vêtements ornés de médaillons bruns aux méandres compliqués, comme nous les trouvons sur les linceuls coptes. Un manteau à l'ranges l'entoure. Sa main droite, dont il ne reste que deux doigts, était levée; la gauche lient la boucle de fleurs. On peut dire que dans cette peinture il n'y a plus de représentation isiaque (Pl. XLV).

Google translate version:

Figure 75 shows us again the intersecting circumferences of the red line on a dark green background; the voids are occupied, sometimes by dextrous swastikas, a sign of light and immortality, by flowers with four petals, by very stylized sinister swastikas, and by solar points surrounded by small stellar points (Pl. XXXVI, D ).

[...]

Fig. 75--The head has an expression of very singular sadness, because all the other portraits show the ecstasy of the beyond. This woman has jewelry, she is draped in clothes adorned with intricate meandering brown medallions, as we find them on Coptic shrouds. A cloak in the fringes surrounds it. Her right hand, of which only two fingers remain, was raised; the left tie the flower loop. We can say that in this painting there is no longer an Isiac representation (Pl. XLV).

Émile Étienne Guimet. (1912). Les Portraits D'Antinoé, Au Musée Guimet. Annales du Musée Guimet, Bibliothèque D'Art. Tome Cinquiéme (Volume 5). Plate XXXVI, figure D, page 30. Image of figure 75 in Plate XLV on page 37, text describing figure 75 on page 39-40.

https://archive.org/details/lesportraitsdant00guim/page/30/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/lesportraitsdant00guim/page/n93/mode/2up

***

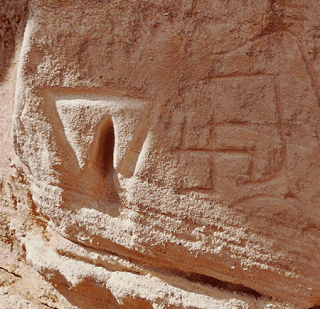

Swastika carving in Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt. Swastika dated from the "Christian" era of the site, 395–641 AD, next to a pubic triangle from the Dynastic period (ca. 2500-332 BC). Found at site CO40.

Figure published in: Pawel Polkowski. The Life of Petroglyphs: A Biographical Approach to Rock Art in the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt. American Indian Rock Art, Volume 41. James D. Keyser and David A. Kaiser, Editors. American Rock Art Research Association, 2015, pp. 43–55.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/A-pubic-triangle-next-to-a-swastika-Site-CO40_fig6_317583161

***

Strip of woven silk with green swastikas. Click the link to see the full cloth. From Qau-el-Kebir, near Asyut, Egypt, ca. 300-600 AD. Accession number T.231-1923 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O184378/textile-fragment-unknown/

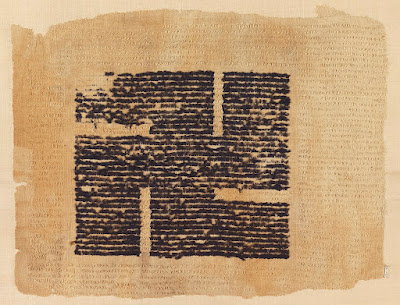

Square textile with four swastikas, 500s-700s AD, from ancient Oxyrhynchus (modern Behnesa), Egypt. Accession number 1262-1904 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O264401/textile-fragment-unknown/

Square textile with four swastikas, 600s-700s AD, from ancient Oxyrhynchus (modern Behnesa), Egypt. Accession number T.127-1922 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O264384/woven-linen/

Portion of a linen cloth with large swastika. 300s-400s AD, produced in Akhmim (Panopolis), Egypt. Accession number 283-1889 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O354861/hanging/ --(Click on the image on the right to see full cloth.)

Cloth panel with swastika decorations. 300s-400s AD, Egypt, precise location unknown. Accession number T.229-1962 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O306721/cloth-panel-unknown/

Round cloth with swastika in the center. 300s AD, produced in Akhmim (Panopolis), Egypt. Accession number 904-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O264473/woven-linen/

***

The Victoria and Albert Museum has many other examples of Egyptian textiles with swastika fret patterns:

Panel from a linen cloth with with swastika fret pattern. 200s-300s AD, produced in Akhmim (Panopolis), Egypt.

Accession number 812-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O264478/woven-linen/

Panel from a linen cloth with with swastika fret pattern. 300s-400s AD, produced in Akhmim (Panopolis), Egypt.

Accession number 881-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O361149/panel/

Linen cloth fragment with swastika fret pattern. Byzantine period, ca. 400-700 AD, location unknown.

Accession number 874-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O368155/fragment/

Shoulder-band from a linen tunic with swastika fret pattern. 200s-300s AD, produced in Akhmim (Panopolis), Egypt.

Accession number 800-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O264481/woven-linen/

Panel from a linen cloth with swastika fret pattern. 200s-300s AD, location unknown.

Accession number 801-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O264480/woven-linen/

Panel from a linen cloth with four swastika frets arranged in a swastika-like manner. 400s-500s AD, produced in Akhmim (Panopolis), Egypt.

Accession number 753-1886 in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O360928/panel/

***

Carving with four fret swastikas arranged in a swastika-like pattern. From the Christian village of Bawit, Egypt, 6th century AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession number 07.228.38.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/454042

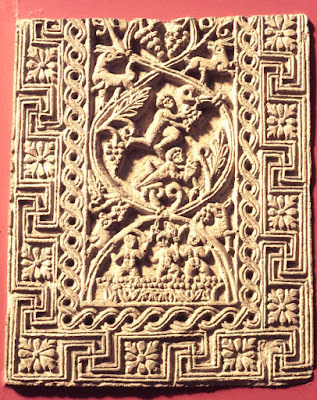

Limestone stela with religious scene, 7th century AD. In the collection of the British Museum, London, UK. Museum number EA1798, registration number 1928,0413.2.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA1798

***

Bed cover from 300-600 AD, Egypt, precise location unknown. Museum number and registration number 1901,0314.26 in the collection of the British Museum, London, UK.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1901-0314-26

Swastika on part of a sarcophagus. Egyptian Museum of Berlin, Germany. Date, origin, and catalog number of artifact not specified.

Photo uploaded by Flickr user tofu_mugwump, 2005.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tofu_mugwump/2056442612/

Sudan

Kingdom of Kush (Meroitic Kingdom)

For millennia, the land of Nubia had been culturally and politically connected with ancient Egypt. By 1000 BC, Kush had become an independent kingdom (which even conquered Egypt and ruled as its 25th Dynasty). The Meroitic period of Kush was its final period, lasting from around 540 BC until the 300s AD.

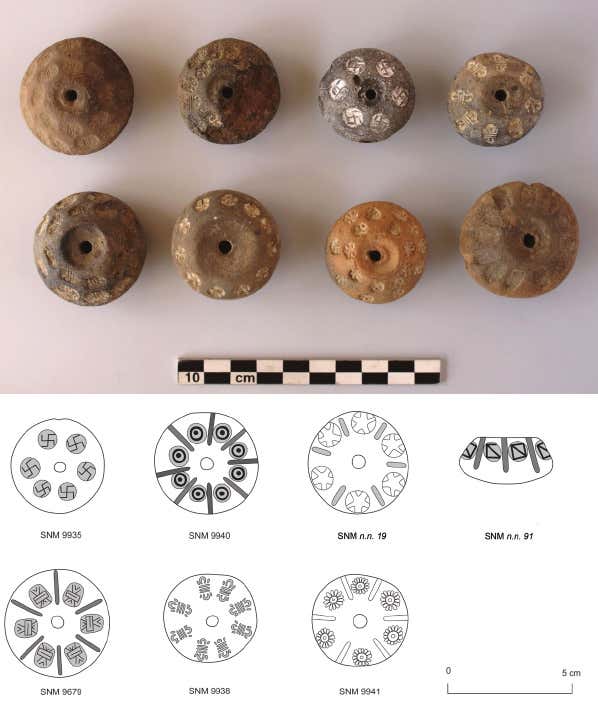

Spindle whorl from Abu Geili, Sudan, ca. 100-400 AD. In the collection of the Sudan National Museum, reference number SNM 9935. Image published in plate 9 in Yvanez (2016).

Elsa Yvanez. (2016). Spinning in Meroitic Sudan. Textile Implements from Abu Geili. Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies, 3(9): 153-178.

https://www.academia.edu/12159298/Spinning_in_Meroitic_Sudan_Textile_Implements_from_Abu_Geili

Description: "Fig. 3. Funerary stelae of a Meroitic lady and her son (?), from the cemetery of Karanog (Lower Nubia, c. 100-200 CE), Cairo Egyptian Museum inventory number JE40229. (Image: Reproduced from Wenig 1978: 205-206, no 127." Image republished in Yvanez (2018a). Yvanez (2018b), fig. 4, says it's from grave 275.

Elsa Yvanez (2018a). TexMeroe: the archaeology of textile production in the kingdom of Meroe, new approaches to cultural identity and economics in ancient Sudan and Nubia. Archaeological Textiles Review, 60: 105-109.

https://www.academia.edu/51055342/TexMeroe_the_archaeology_of_textile_production_in_the_kingdom_of_Meroe_new_approaches_to_cultural_identity_and_economics_in_ancient_Sudan_and_Nubia

Description: "Fig. 6. Large rectangular cotton fabric with blue swastikas and stripes, from Gebel Adda, Royal Ontario Museum 973.24.3528."

Elsa Yvanez. (2018b). Clothing the elite? Patterns of textile production and consumption in ancient Sudan and Nubia. In A. Ulanowska, M. Siennicka, and M. Grupa (eds.), Dynamics and Organisation of Textile Production in Past Societies in Europe and the Mediterranean. Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae, 31: 81-92.

https://www.academia.edu/38111132/Clothing_the_elite_Patterns_of_textile_production_and_consumption_in_ancient_Sudan_and_Nubia

***

In addition to the confirmed examples of swastikas listed above, I have not yet been able to confirm the existence of swastikas from the Jebel Barkal temples.

"Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of Kush and on pottery at the Jebel Barkal temples,[59]"

With the citation:

Dunham, Dows. (1965). A Collection of 'Pot-Marks' from Kush and Nubia. Kush: Journal of the Sudan Antiquities Service, 13: 131–147.

I have not been able to find this article online, so I cannot confirm or provide further information.

Kingdom of Makuria

After the collapse of the Kingdom of Kush, a number of smaller kingdoms arose in the region, including the Kingdom of Makuria. Makuria declined after the 1300s AD, ceasing to exist by the 1500s.

Swastika meander pattern found on an artifact from the cemetary of el-Zuma in Upper Nubia, 450-550 AD. Figure 11:Z4/8.4 in Then-Obłuska (2018).

Joanna Then-Obłuska. (2018). Royal ornaments of a late antique African kingdom, Early Makuria, Nubia (AD 450–550). Early Makuria Research Project. Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 26(1): 687-718.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326361608_Royal_ornaments_of_a_late_antique_African_kingdom_Early_Makuria_Nubia_AD_450-550_Early_Makuria_Research_Project

Ethiopia

Rock-hewn churches

Swastikas of different forms can be seen in the architecture of rock-hewn churches in Ethiopia. The most notable of these are in the town of Lalibela. There are around a dozen of these churches in Lalibela, most of which were constructed around the 12th and 13th centuries AD.

They are especially notable in the windows of the Biete Maryam church (pictured below). I do not know how many of the churches in total have swastikas.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bet_Maryam,_Lalibela,_Ethiopia_-_panoramio_(1).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bete_Maryam_01.jpg

Presumably this is also a window in the Biete Maryam church.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Skastika_symbol_in_the_window_of_Lalibela_Rock_hewn_churches.jpg

Processional Cross with swastikas, used in a Lalibela church.

https://web.archive.org/web/20220824155609/http://worldheritage.si.edu/en/sites/lalibela.html#artifacts

https://web.archive.org/web/20170820161451/http://worldheritage.si.edu/en/sites/lalibela.html

The image linked below shows a priest holding this cross in front of the Biet Mariam Church:

https://www.alamy.com/coptic-priest-holding-the-cross-in-front-of-biet-mariam-church-in-image68969519.html

***

Church of Abreha we Atsbeha, Eastern Tigray region. Rock-hewn church, ca. 700-1100 AD. Ceiling has patterns with two different types of swastikas.

Photos taken by Jean-Claude Latombe.

https://ai.stanford.edu/~latombe/mountain/photo/ethiopia-apr-may-2015/7.htm

Tanzania

Swastika used as an indigenous symbol(?)

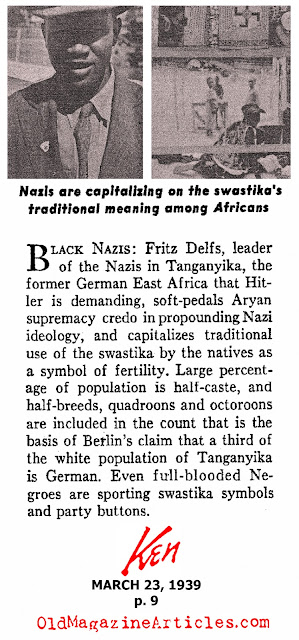

Article published in Ken magazine, March 23, 1939. Click image for full size. Man on the left has a swastika pin/button and the photo on the right shows a swastika on a flag or cloth. This paragraph is the entire "article". Unfortunately, there is no additional information.

The article says this is a native symbol, and the proportions of the swastika's arms in the top right photo show it is not merely an imported National Socialist flag. If anyone has more information as to the name of this symbol or which culture(s) it is common with in Tanzania, please leave a comment on the discussion post:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/2020/10/african-swastikas.html

Article text:

"Nazis are capitalizing on the swastika's traditional meaning among Africans.

Black Nazis: Fritz Delfs, leader of the Nazis in Tanganyika, the former German East Africa that Hitler is demanding, soft-pedals Aryan supremacy credo in propounding Nazi ideology, and capitalizes traditional use of the swastika by the natives as a symbol of fertility. Large percentage of the population is half-case, and half-breeds, quadroons and octoroons are included in the count that is the basis of Berlin's claim that a third of the white population of Tanganyika is German. Even full-blooded Negroes are sporting swastika symbols and party buttons."

Swastika used as a Hindu symbol

For centuries, Tanzania had interacted with India through the Indian Ocean trade network. However, in the 1800s, the British colonial empire began the Indian indenture system, transporting over a million Indian slaves to many of their colonies throughout the world. In the process, these Indians spread their religion and use of the swastika to Tanzania and many other nations.

Likely a Hindu temple (note the four dots surrounding each swastika) said to be in the city of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Exact name and location unknown.

The URL of the photo on the following website is "3i - Tansania-mi"

https://web.archive.org/web/20181031071918/http://www.worldglobetrotters.com/Links/Swastika/swastika.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20181027194525im_/http://worldglobetrotters.com/Links/Swastika/3i%20-%20Tansania-mi.jpg

On this website (slide 7), it claims it is in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

https://www.slideshare.net/kansaldeepakk/swastik-a-symbolof-health

House with swastikas above the doorways in the city or region of Arusha, northern Tanzania.

Photo uploaded by Flickr user osirizzle in 2007.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/osirizzle/2344276117/in/photostream/

Detail of a Hindu swastika painted on a door. Stone Town, Zanzibar, Tanzania. Photo taken by Melissa Jooste, 2012. (See links for full image.)

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-arabic-hindu-style-art-carved-door-stone-town-zanzibar-tanzania-172066248.html

https://www.alamy.com/decorative-old-door-stone-town-zanzibar-unguja-island-tanzania-image328384655.html

Bus with swastikas in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Photo uploaded by Flickr user rorymccann in 2007. The photographer believes it is related to the Hindu population in the city.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/rorymccann/3431926903/

Vehicle with swastikas. Location unknown, but the photographer was on a trip to the Selous Game Reserve in southern Tanzania.

Photo uploaded by Flickr user amanda_gardner in 2007.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/amanda_gardner/917060879/

Kenya

Swastika used as a Hindu symbol

Similar to Tanzania, Kenya has been connected to the Indian Ocean trade network for millennia, and the cultural influence of Indosphere cultures in Kenya accelerated under the Indian indenture system.

Floor mosaic in the Swaminarayan Hindu temple, Mombasa, Kenya.

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-floor-of-indian-temple-in-mombasa-kenya-africa-16330901.html

https://www.flickr.com/photos/magdeburg/10865843764

3. Southern Africa

Lesotho

The following image shows a swastika painted on a phone booth in Lesotho. The person who uploaded the photo doesn't mention its meaning. Could it be graffiti from Neo-Nazi "white" South Africans intended to intimidate the locals? On the other hand, it looks to be very carefully painted, unlike typical sloppy graffiti.

Photo uploaded by Flickr user Seth Frantzman in February 2006.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/55073053@N00/105237418/

4. Egyptian Revival Art

Beginning in 1798, Napoleon started a military campaign to conquer Egypt. During this time period, France organized a series of scientific and archaeological expeditions, spurring Western fascination with the Pyramids, Sphinx, Rosetta Stone, etc., and leading to the creation of "Egyptology", which reached its peak under British colonial domination of Egypt. From the early 1800s and continuing well into the 1900s, Egyptian Revival architecture in Western nations used elements of ancient Egyptian architecture and design.

Although archaeological findings suggest the swastika did not become common in Egypt until its integration into the Roman Empire and the spread of Christianity, some examples of Egyptian Revival symbolism are associated with swastikas.

Swastika appearing on the facade above the left entryway of the Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University, in New Haven, Connecticut, USA. The building was completed in 1930. The full facade contains imagery of many different cultural symbols, including an Egyptian Nekhbet vulture. According to a publication by the library, the ship is supposed to be Phoenician, rather than Egyptian.[6]

It is unclear which culture the swastika is supposed to represent. Click the Wikipedia link to see a larger image.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sterling_Library_bas_relief_panorama.jpg

Wilmington Public Library, Delaware, USA. Completed in 1922.

Photos uploaded by Flickr user howderfamily.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/96225726@N08/13353870914/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/96225726@N08/13353633793/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/96225726@N08/13353871644/

5. Other Symbols

These are not swastikas in the strict sense, but they bear some loose similarity and are also found in other cultures which used the swastika in different places in the world.

Tetraskelion

The triskelion is a spiral with three "legs" or "arms". It originated in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, and is often found in cultures using the swastika. It has rotational symmetry similar to a swastika and three-legged triskelions sometimes get mistaken for swastikas by individuals who don't recognize the symbols.

A tetraskelion is a variant of the triskelion with four legs, giving it an appearance similar to a swastika. In the strict sense, I believe the tetraskelion is a distinct motif which should be considered a variant of the triskelion, rather than a swastika. The most notable different between a tetraskelion and a swastika is that the center of a swastika is two crossing lines, while the center of a tetraskelion is a "chunky-looking" empty space.

When writing this article, I did not search specifically for examples of tetraskelions, but I did find an example of one from ancient Egypt. Interlocking tetraskelions were found on the ceiling of Room N5 in the Palace at Malkata. Pharaoh Amenhotep III constructed a palace and founded a city surrounding it. His rule lasted from approximately 1390 to 1350 BC.

Image from the website of the Institute of Egyptology, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan.

https://www.egyptpro.sci.waseda.ac.jp/e-mp.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malkata

A very similar pattern from the Theban Necropolis be seen on the following plate:

"Ornementation des Plafonds: Postes & Fleurs. Nécropole de Thèbes -- XVIIIe. à XXe. Dyn."

This is on page 45/81 (pdf numbering) on the BnF Gallica link below. A high resolution scan by the New York Public Library Digital Collections is also linked below.

Émile Prisse d'Avennes. (1878). Histoire de l'art égyptien d'après les monuments: depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'a la domination romaine. Tome Premier: Architecture. Paris: Arthus Bertrand, Éditeur.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7300477j/f45.vertical

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-6861-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

***

A few additional swastika-like tetraskelions:

Embroidery from El-Azam, Egypt, ca. 1100-1399 AD. In the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK. Accession number: 809-1898.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O363374/embroidery/

Mamluk-era embroidery, El-Azam, Egypt, ca. 1250-1516 AD. In the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK. Accession number: 772-1898.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O363001/embroidery/

"Solomon's Knot" motif

In the top-left of the following image, there is a tetraskelion that some have called a "swastika".

It is difficult to tell from the tracing, but in this drawing, each of the four "arms" of the symbol appear to be slightly offset from one another. Therefore it is a tetraskelion-like symbol rather than a true swastika.

In the bottom-right there is a Solomon's Knot motif, and in the upper-right another knot motif, suggesting top-left is indeed another type of knot, rather than intended as a swastika.

Rock carving from inner Angola, c. 600 - 1 BC.

Illustration and information published in Coimbra (2011),[7] citing Redinha (1948).[8]

Four rotated triangles

I've noticed a four-fold geometric motif of triangles is often seen throughout western and central Africa. Some blogs will call this a "swastika". Perhaps in cultures where the "standard" swastika is very common we might consider this a variation of the swastika, but for cultures where the swastika is less common, it should be considered a distinct four-fold motif.

For example, here is a Kuba textile (note the bottom right and top left).

Kuba textile in the Arts of Africa collection of the Brooklyn Museum, ca. 1800s-1922. Accession number 22.1523

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/22381

This pattern appears as a panel in the Nigerian Adire textile with swastikas shown in the section on Adire above. Panel 23 of 41.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/

This pattern is common in Ghanaian Kente cloth, often with jagged squared edges. Many blogs call this motif "Apremo (Canon)" or "Apremo-Canon". If you do an internet search, there are dozens of random blogs and forum posts copy-pasting the exact same paragraph about this this symbol, so I'm not sure I trust their analysis on the meaning and origin of the symbol to be accurate.

According to some Adinkra symbol guides on the internet, a group of four of these symbols is called Kyemfere.

***

This motif is found throughout the world. For example, in medieval European heraldry it is called a "gyronny".

It can also be seen in Native American motifs:

Four triangles motif used by Native Americans. Figure 316h, page 935, from Thomas Wilson, The Swastika (1896).

Motifs similar to multiple-armed sun wheel or Black Sun

Yoruba Adire Textile #1012, collected by the Hamill Gallery of Tribal Art in Boston. This textile was featured in the gallery's exhibition "Take a Seat", which took place from February 2 - March 30, 2013. Textile was sold to a collector. Said to be from Nigeria. Age and precise origin unknown.

https://www.hamillgallery.com/YORUBA/YorubaTextiles/AdireTextiles/Adire1012.html

This motif appears in a number of panels in the Nigerian Adire textile with swastikas shown in the section on Adire above.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O297293/textile-unknown/

Mbuti (Pygmy) Barkcloth from the Ituri forest, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Item number #mbc-07 in the Indigo Arts Gallery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Piece sold to a collector. Date unknown.

https://web.archive.org/web/20080516043643/http://www.indigoarts.com/gallery_mbuti_barkcloth7.html

5. Index of Names and Meanings of the Swastika

The word "swastika" comes from the Sanskrit language and its etymology reveals a meaning specific to the ancient Sanskrit-speaking Vedic culture of India. The fact that the word we use for this symbol is so culture-specific (rather than a general geometric term, such as hooked cross) has unfortunately led many to believe that the Vedic interpretation of the symbol is somehow the most correct or original.

The Vedic culture was far from the first to use the swastika, and their conception of its meaning is far from universal. Different cultures have different names for the swastika, attribute different meanings to it, and it's likely the meaning has changed throughout time within particular cultures.

Now that we have collected various images of swastikas, we begin the difficult task of attempting to compile the names and meanings African cultures give this symbol, thereby arriving at a less Vedic-centric understanding of the swastika.

The information below is based on the information that has been presented in this article. If you are from one of these cultures or have more information, please post on this article's discussion page. As we can see, information is scarce.

| Culture | Location | Name for Swastika | Meaning for Swastika |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akan cultures | Ghana | ? | Decoration on brass weights used to measure gold (mrammou) |

| Bono/Abron and related cultures (including Ashanti, Fante, Dagomba, and an unspecified Togolese culture) | Ghana | Nkontim; Nkotimsefuopua; Nkotimsefoc pua | Named after a hairstyle of the Queen Mother's attendants; loyalty and service. |

| Baoulé (Baule) | Ivory Coast | ? | Decoration on brass weights used to measure gold (mrammou) |

| ? | Congo | ? | "The four important moments of life: birth, maturity, death, and rebirth." |

| Ancient Egyptian | Near Dakhla Oasis, Egypt | ? | Personal symbol? |

| Egyptian | Egypt | ? | Variant of cross used among early Christians |

| Tanzanian Hindus | Tanzania | Swastika | Hindu religious symbol |

| Kenyan Hindus | Kenya | Swastika | Hindu religious symbol |

Footnotes

[1] Robert Sutherland Rattray. (1927). Religion and Art in Ashanti. Page 243 and 265.

https://archive.org/details/religionartinash0000ratt/page/n381/mode/2up

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Adinkra_Rattray.JPG

[2] Smithsonian Music. Stamp. Object number 2010-10-351. (Accessed May 2023).

https://music.si.edu/object/nmafa_2010-10-351

[3] University of Ghana. (April 1, 2019). International Week 2019.

https://www.ug.edu.gh/news/international-week-2019

[4] Theodore Monod. (September-October 1941). On the Origin of a West African Swastika. Man, Vol. XLI: page 93.

https://archive.org/details/dli.ministry.16762/page/n111/mode/2up

[5] Diary of Ernest Dockray, a British soldier from the East Africa theater of WWI from 1915-1919. "Addendum – “New” things seen in Africa (1918) – Part 3". Diary entry published online by his grandson, Nick Denbow, 2015.

https://dockraydiary.wordpress.com/2015/01/16/addendum-new-things-seen-in-africa-part-3/

[6] The Yale University Library Gazette. (April 1931). The Sterling Memorial Library. Vol. 5, No. 4. Page 81.

http://digital.library.yale.edu/digital/collection/rebooks/id/85652/rec/1

[7] Fernando Coimbra. (2011). The Astronomical Origins of the Swastika Motif. Proceedings of the International Colloquium - The intellectual and spiritual expressions of non-literate peoples. Atelier, Capo di Ponte: 78-90.

https://www.academia.edu/2951519/The_astronomical_origins_of_the_swastika_motif

[8] José Redinha. (1948). As gravuras rupestres do Alto Zambeze e primeiratentativa da sua interpretação. Publicações Culturais, nº 2. CompanhiaDiamantes de Angola, Lisboa: 67-82.