The swastika independently arose in the New World, being in use for nearly 2000 years North America and South America. Just like in the Old World, the oldest uses of the swastika in North and South America tend to be most strongly correlated with agricultural societies.

Native Americans have always been the most prolific users of the swastika in the New World, although the symbol's popularity widened by the late 1800s. During this time, archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann published numerous books and photos relating to the archaeological excavations at Troy. The artifacts uncovered there had many swastikas, causing a tremendous interest in this symbol in Western nations. It was mostly used as a decoration or generic symbol of "good luck." Notably, it can be found in numerous architectural ornaments, post cards, and even business logos in the US and elsewhere from the 1870s to 1930s.

This article does not attempt to exhaustively cover every single instance of these purely decorative swastikas, but instead attempts to focus primarily on swastikas used by various Native Americans and non-Westerners. Many of the artifacts listed are only a few hundred years old, so it may be possible that some of the cultures listed here only started using the swastika once it gained massive popularity in the late 1800s. Due to the prevalence of grave robbing and the intensity of cultural destruction since contact with Western civilization, it can be difficult to find examples of accurately-dated ancient artifacts.

Nevertheless, a number of swastikas dating back thousands of years have been found throughout the New World, demonstrating the long-standing and widespread use of the swastika in North and South America. In the American Southwest, swastikas were used by Ancestral Puebloans, the Hohokam, and other ancient cultures. Eastwards, in the Mississippi River basin, the Hopewell and Mississippian cultures used the swastika. In ancient Peru and Colombia, the Moche, Sican/Lambayeque, Wari/Huari, and Tiwanaku/Tiahuanaco cultures used swastikas and swastika-like motifs. In Mesoamerica, there are multiple examples of the Maya civilization using swastikas, but it is unclear how extensively this symbol was used.

These four regions constitute the primary areas of ancient swastika use in the Americas. With the information we have, it appears that the swastika became common in North America, Mesoamerica, and South America by approximately 500-1000 AD. In North America, the oldest examples are among the Hopewell culture, likely appearing around 200 BC - 200 AD. In South America, the swastika may have appeared around 100 AD - 300 AD. It is not yet clear if the swastika arose independently in each of these areas, or if its use was spread through cultural exchange. We have next to no information about the names and meanings of the swastika in these cultures.

In modern times, over the past century-and-a-half the swastika and swastika-like symbols have been used by dozens of cultures in the Americas, over an area ranging from Alaska and Labrador in the north, to Chile and possibly Paraguay in the south.

How many more swastikas remain to be found in the New World?

If you have additional information or artifacts to share, please post them on the discussion page for this article:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/2021/04/native-american-swastikas-discussion.html

To return to the index of swastika articles, click here:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/the-swastika-aryan-symbol.html

Table of Contents

- 1. North America

- Native Americans in the US Southwest

- Native Americans elsewhere in the United States

- Hopewell culture

- Mississippian culture

- Mississippian culture, Nodena phase

- Cahuilla

- Delaware (Lenape)

- Kaw (Kanza/Kansa)

- Lakota (Teton Sioux)

- Mashpee Wampanoag

- Meskwaki (Fox)

- Nanticoke

- Nez Perce (Nimíipuu)

- Ojibwe (Chippewa)

- Osage

- Passamaquoddy

- Pomo

- Potawatomi

- Sac (Sauk)

- Secotan

- Skokomish (Coast Salish)

- Tlingit

- Wyam

- Yaqui

- Chilocco Indian Agricultural School

- Chicano Park mural

- Use by the US military, US government, Anglo-Americans, etc.

- Canada

- 2. Mesoamerica and the Caribbean

- 3. South America

- 4. Unconfirmed Swastikas

- 5. Other Unconfirmed and Unknown Swastikas

- Artifact from unspecified Northeastern USA culture

- Artifact from unspecified "Plains Indians" culture

- Artifact from unspecified Pacific Northwest USA culture

- Artifact from unspecified US Southwest culture

- Makah or Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka)

- Unconfirmed Mississippian culture artifacts

- Hupa, Yurok, or Karok

- Maidu

- Artifact from unspecified "Plains Indians" culture

- Unconfirmed Nez Perce (Nimíipuu) artifact

- Unconfirmed Skokomish (Coast Salish) artifact

- Unknown Native American ceramic

- Unknown Native American(?) jewelry

- Teotihuacan

- "Mexican" hieroglyph from unspecified culture

- Cerro de la Máscara petroglyph

- Tarascan state (Purépecha Empire)

- Pedra Pintada rock art(?)

- Unspecified Brazilian ossuary

- Additional unknown photos with no information

- 6. Swastika-like symbols

- Four-fold whorls

- Two conjoined S-shapes

- Tetraskelions

- Spirals

- Four-fold arrangement of bird motifs

- Four triangles arranged in a swastika-like pattern

- Sunwheel or Black Sun-like symbol

- Passamaquoddy and Wampanoag symbol

- So-called "Aztec swastika"

- Mississippian culture serpent motif

- Mesoamerican calendars

- 7. Index of Names and Meanings of the Swastika

- Footnotes

1. North America

Native Americans in the US Southwest

Introduction

Within the United States, the swastika is most prevalent among Native American nations in the Southwest. This includes the sedentary agriculturalist Puebloan peoples (among whom we find the oldest examples of swastikas in this region) and traditionally nomadic hunter-gatherer cultures they were in contact with, such as the Navajo and Apache.

As part of a WWII propaganda campaign, various Native American groups in Arizona agreed to stop using the swastika in 1940. Throughout the 1930s, "white" sellers of Native American arts had previously discouraged Native Americans from using the swastika and even discontinued selling products with the swastika,[1] despite the high popularity of the symbol in prior decades. It has been suggested these "white" merchants were the ones who 'convinced' Native Americans to reject the swastika, so they could continue selling their wares.

Popularity of the design waned, eventually resulting in a proclamation signed on February 28, 1940, in Tucson by representatives from the Hopi, Navajo, Apache, and Tohono O’odham (formerly Papago) tribes, renouncing and banning the use of the swastika on their artwork. The text of this parchment document read:

"Because the above ornament which has been a symbol of friendship among our forefathers for many centuries has been desecrated recently by another nation of peoples, Therefore it is resolved that henceforth from this date on and forever more our tribes renounce the use of the emblem commonly known today as the swastika or fylfot on our blankets, baskets, art objects, sandpaintings and clothing."

It is likely that the signing of the document by members of southwest tribes was a form of public relations arranged by area traders to distance Indian handicrafts from the atrocities occurring overseas.[1]

Further reading suggests this declaration against the swastika was by no means accepted by all Native Americans in the region, as many were keenly aware that this declaration was a continuation of cultural destruction at the hands of Western colonists. Some Anglo-Americans spoke out against this as well.[2] The signing apparently generated enough interest to be covered in local newspapers as far as Pennsylvania. The newspaper below says the signing occurred on February 25th, indicating this may have been a multiple-day-long event.

Tuesday, Feb. 27. [1940]

Dissention arose ... in the Hopi Indian tribe over use of the swastika in blanket and basket weaving.

Two days ago a Hopi chief, John Joesicki, placed his signature along with those of Papago, Navajo and Apache leaders on a proclamation declaring they would no longer use the design because it ‘has been desecrated recently by another nation of peoples.’

Today, however, representatives for the ancient Hopi villages in northern Arizona said there was ‘no sense’ in giving up the swastika, a symbol of friendship among Indians for many generations.

‘We know of another nation that desecrates the white man’s cross,’ they said. ‘Because of this, should the cross be thrown way?’[3]

Caption for photo above:

"Picture released on February 28, 1940 of Hopi artist Fred Kabotie (L) and Apache Miguel Flores (R) along with other Indian tribes of Arizona, signing the parchment document banning the use of the Swastika from all designs in their basket weaving and blanket making and other hand-crafted objects, against Nazi "act of opression", in Tucson, Arizona."

Caption for photo above:

"2/28/40-Tucson, Arizona: Florence Smiley and Evelyn Yathe, Navajos of Tucson, Arizona are shown signing the imposing parchment document which formally outlawed the Swastika symbol from designs in Indian art, such as basket and blanket weaving. Four tribes, Navajos, Papagos, Apaches and Hopis banned the symbol which was in use by the Indians long before it came to have a sinister significance. The document tells why Indians banned it."

This image is the one that seems to have been included in most newspapers of the time.[4][5][6][7]

"Four Indian Tribes End Use of Swastika.

Four tribes of Arizona Indians, the Navajo, Papago, Apache and Hopi, today through their head-men at the Indian concave here banned the use of the swastika from all designs in their basket weaving and blanket making.

[...]

Signatures on the imposing parchment document draw up by one of the Indian artist included those of Roman Pancero, Papago; Charles De Courcy, Navajo; Joe Joesicki, Hopi; and Miguel Flores, Apache.

The proclamation, as prepared by the Indians, shows a large black swastika at the top which has been crossed out.

[...]

For many years the swastika has been a commonly used design by the basket weavers and the blanket weavers both of whom included it in their domestic workmanship more than in commercial objects.

[...]

The Indians, gathered here for the annual Indian Day programs of the midwinter rodeo, held a solemn ceremony at noon as they prepared to sign the proclamation.

A basket, a blanket and some hand-decorated clothing were placed together, then some of the colored sand used by Navajo sand painters was sprinkled over them and the various pieces were burned.

None of the Indians present could say the exact number of years the swastika has been a symbol of their handicraft, but the Papago claimed it has been used in their baskets for many generations."[8]

In the US, Native American use of the swastika has been making a resurgence since the 1960s-1970s, with the rise of various Native American activist groups who have courageously pushed back against the taboos and 'aesthetics' of Western civilization.

The following list of Native American nations using the swastika is not exhaustive. Again, many of the artifacts are only a few hundred years old. However, they nevertheless demonstrate the extensive and long-term use of the swastika in the American Southwest.

Ancestral Puebloan

Archaeologists have named the ancient people who inhabited a large part of the northern section of the American Southwest as the "Ancestral Puebloan" people. The Ancestral Puebloans were agriculturalists who lived in large villages. By the 1300s AD, perhaps due to changing climatic conditions, they left the northernmost parts of their territory and migrated southward. In their absence, the Navajo people moved in.

In historic US records, they were referred to as the Anasazi. The word Anaasází is a Navajo word meaning "ancestors of our enemies", indicating a long-standing conflict between the semi-nomadic Navajo hunter/herders and the sedentary agriculturalist Puebloan cultures.

Present-day Puebloan cultures such as the Acoma, Hopi, and Zia are descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans.

Antelope House ruins at the Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona. Swastika overlooking the ruin.

(Photographer incorrectly says it may be the Lodge ruin). Photo by Tom Mahood, 2013.

https://www.otherhand.org/home-page/archaeology/canyon-de-chelly-54-62013/

Antelope House was inhabited from approximately 1050-1270 AD.[10]

Photos from above do not make it clear if this is a swastika with all four "arms", or if the bottom hook is missing:

Photo by Flickr user rcaustintx, June 2, 2019.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/9681508@N03/51342321058/

Petroglyphs in Zion National Park, Utah. Cave Valley. Photo by the website Utah Petroglyphs, 2016.

https://web.archive.org/web/20170808015559/http://utahpetroglyphs.org/?p=169

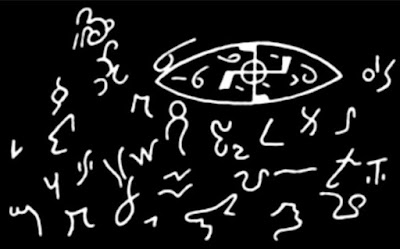

Painting said to be "Rock painting of shaman in Moab, Utah". I am unable to find more information on this. Note, however, that the swastika and the symbols on the circle surrounding it are the same as on the Hopi gourd rattle (see the section on the Hopi below).

https://web.archive.org/web/20081222025718/http://worldreligion.nielsonpi.com/5ritual.html

Black-on-white Ancestral Puebloan bowl. Date and Origin unknown.

https://forums.arrowheads.com/forum/general-discussion-gc5/native-american-pottery-non-lithic-artifacts-gc23/136564-hohokam-bowl-and-swastika-symbol?p=136566#post136566

https://www.treasurenet.com/forums/north-american-indian-artifacts/438137-hohokam-bowl-swastika-symbol.html#post4244440

Bowl from the Pueblo Bonito archaeological site in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico, ca. 850-1150 AD. Catalog number A336196-0 in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/anth/

Ancestral Puebloan ladle from "Northeast Arizona, Upper Gila Area, Salt Area". In the collection of the Penn Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Object number 29-78-894, URL identifier 343425.

https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/343425

***

In The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson, he cites the work of Gustaf Nordenskiöld, who was the first archaeologist to study the Mesa Verde area.

"G. Nordenskiöld, in the report of his excavations among the ruined pueblos of the Mesa Verde, made in southwestern Colorado during the summer of 1891, tells of the finding of numerous specimens of the Swastika. In pl. 23, fig. 1, he represents a large, shallow bowl in the refuse heap at the “Step House.” It was 50 centimeters in diameter, of rough execution, gray in color, and different in form and design from other vessels from the cliff houses. The Swastika sign (to the right) was in its center, and made by lines of small dots." - Thomas Wilson (1898)

Gustaf Nordenskiöld (1893). The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, Southwestern Colorado. Plate 23 is linked below. It is described on page 82.

https://archive.org/details/cliffdwellersofm00nord/page/196/mode/2up

From what I have read, the Step House site dates to around 600-1200 AD.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mesa_Verde_National_Park

"...His pl. 27, fig. 6, represents a bowl found in a grave (g on the plan) at “Step House.” Its decoration inside was of the usual type, but the only decoration on the outside consisted of a Swastika, with arms crossing at right angles and ends bent at the right, similar to fig. 9." - Thomas Wilson (1898)

Gustaf Nordenskiöld (1893). The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, Southwestern Colorado. Plate 27 is linked below. It is described on page 40.

https://archive.org/details/cliffdwellersofm00nord/page/212/mode/2up

"...His pl. 18, fig. 1, represented a large bowl found in Mug House." - Thomas Wilson (1898)

(Wilson made a typo, it is plate 28.)

Gustaf Nordenskiöld (1893). The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, Southwestern Colorado. Plate 28 is linked below.

https://archive.org/details/cliffdwellersofm00nord/page/214/mode/2up

The Mug House site dates from around 700-1300 AD:

Arthur H. Rohn. (1971). Wetherill Mesa Excavations: Mug House, Mesa Verde National Park - Colorado. Page 18.

https://archive.org/details/mughousemesaverd00rohn/page/18/mode/2up

***

Description: "Anasazi Snowflake Black on White "Angry" Goose, ca. 1100 - 1250 AD". Sold by Artemis Gallery on the auction website LiveAuctioneers, February 13, 2010. LotID 7058779, LotNumber 0276. Provenance: "Ex-M. Miller Collection, Texas."

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/7058779_anasazi-snowflake-black-on-white-angry-goose

Description: "Large Early Anasazi Pottery Olla, Black & White on Red" Sold by Case Antiques, Inc. Auctions & Appraisals on the auction websites Invaluable and LiveAuctioneers. July 24, 2021, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. Lot 685, CatalogID 703840. Provenance: "The Estates of Ora and Eleanor Eads, Nashville, TN.

https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/large-early-anasazi-pottery-olla-black-white-on-r-685-c-4914f7c82c

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/105985306_large-early-anasazi-pottery-olla-black-and-white-on-red

Description: "Black-on-white ladle, San Juan Anasazi, San Juan County, Utah, 900-1050 AD". Exhibit in the Natural History Museum of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Black-on-white_ladle,_San_Juan_Anasazi,_San_Juan_County,_Utah,_900-1050_AD,_ceramic,_paint_-_Natural_History_Museum_of_Utah_-_DSC07403.JPG

Hohokam

The Hohokam is an archaeological culture located to the southwest of the Ancestral Puebloans, which existed from around 300-1500 AD. The Hohokam built large irrigation systems and had trade networks with the Ancestral Puebloans.

Anthropologists believe the Akimel O'odham ("Pima") and Tohono O'odham ("Papago") are the descendants of the Hohokam.

Petroglyph near Heard Scout Pueblo, Phoenix, Arizona. The "Pueblo" was built by the Boy Scouts. Information on the age of the carvings is unknown.

http://azruins.com/petroglyphs-in-south-mountain-part-1/

Description: "14 Hohokam. Jar, AD 900-1150." In the collection of the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona.

Source:

https://web.archive.org/web/20190504062225/http://fidella.com/photojournals/Pottery2017/index1.html

https://forums.arrowheads.com/forum/general-discussion-gc5/native-american-pottery-non-lithic-artifacts-gc23/136564-hohokam-bowl-and-swastika-symbol?p=136566#post136566

Description: "30N Hohokam Sacaton Red-on-Buff Bowl (Safford Regional Variety)", ca. 950-1125 AD. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20170501174354/http://rarepottery.info/protect/hohokamsacaton.htm

Two swastika petrogylphs, said to be at the Hohokam Pima National Monument, near Sacaton, Arizona. This National Monument contains the archaeological site called Snaketown.

Photos found on the following websites:

https://web.archive.org/web/20160508005518/http://arizonaexperience.org/remember/hohokam-rock-art

https://web.archive.org/web/20160824223211/http://www.azpbs.org/arizonastories/ppedetail.php?id=98

Patayan

The Patayan is an archaeological culture which existed in southwestern Arizona and southern California. Around 700 AD, agriculture and ceramics arrived to the lower Colorado River valley area, beginning the Patayan culture. They engaged in significant trade with the Hohokam culture.

Anthropologists believe present-day cultures such as the Maricopa (Piipaash), Quechan (Yuma), Yavapai are their descendants.

Swastika petroglyph found by StoriesByAlex. He says it was found in a canyon in Black Mountain, Kern County, California.

Photo from Youtube video posted on March 18, 2020.

https://www.storiesbyalex.com/california_ancient_sites

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3uCtoQNTMjE

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Mountain_Rock_Art_District

(Unfortunately, in the video he repeats the incorrect claim that the oldest swastika is from an artifact from Mezine. See the article below for an examination of the Mezine artifact and how it is NOT a swastika):

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/2020/08/the-mezine-carving-is-not-swastika.html

Salado

The Salado is an archaeological culture which existed around 1150 AD - 1400s AD. It was located in southeastern Arizona, between the Hohokam and Mogollon cultural areas. Similarly to these cultures, the Salado engaged in irrigated farming.

Salado culture pottery bowl with swastika-like design, ca. 1200-1600 AD. Object number 667-17-2706 in the California State Parks Museum collections.

http://www.museumcollections.parks.ca.gov/code/emuseum.asp

Description: "14N Salado Gila Polychrome Oval Bowl", ca. 1300-1450 AD. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20170501193243/http://rarepottery.info/protect/saladogila.htm

Acoma Pueblo

The Acoma Pueblo is a village in present-day New Mexico. The village has been inhabited for at least 800 years, making it one of the oldest continuously-inhabited pueblos. This timeframe means the town was established immediately after the Ancestral Puebloans left their large pueblos in the Four Corners region.

Ceramic jar, Acoma Pueblo, ca. 1900-1910. Catalog number CAS 0370-0111 in the collection of California Academy of Sciences (CAS), San Francisco, California.

https://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/anthropology/collections/Index.asp

Apache

The Apache are a collection of related ethnic groups who live mainly in New Mexico and Arizona. Historically, they were nomadic hunters who moved into the Southwest region between 1200 - 1500 AD.

Western Apache culture basket, ca. early 1900s. Catalog number CAS 1983-0001-0014 in the collection of California Academy of Sciences (CAS), San Francisco, California.

https://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/anthropology/collections/Index.asp

Hopi

The Hopi people are descended from the Ancestral Puebloans. Today, the Hopi Reservation is located in Arizona. They live in a number of different villages, and the village of Oraibi (Orayvi) is believed to have been founded 800-900 years ago.

Copy of the Hopi Prophecy Rock belonging to Hopi elder Thomas Banyacya.

The Prophecy Rock is located near Oraibi, Arizona. The original rock carving does not appear to have a swastika on it.

Photos from the 1995 Prayer Vigil for the Earth in Washington, DC. In both cases, the swastika is being used as a sun symbol.

Photos uploaded by Flickr user Tribal Ink News.

Map:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tribalinknews/4559016904/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tribalinknews/4559021050/

Rattle:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tribalinknews/4559019494/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tribalinknews/4559018712/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tribalinknews/4559020426/

1995 lecture by Banyacya. From 28:30 to 30:30 he explains the meaning of the gourd rattle and its symbolism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qfFJFgnmJdE

From minute 20 to 23 he explains the meaning of the rattle further. He says the rattles are made yearly in February or March and given to boys. He also explains the meaning of the Prophecy Rock.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxs8T_RW0I4

Read more about Thomas Banyacya and the Prayer Vigil for the Earth below. In 1948 Banyacya was one of four Hopis who were given the duty of educating the world about Hopi culture and prophecy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Banyacya

https://www.nytimes.com/1999/02/15/us/thomas-banyacya-89-teller-of-hopi-prophecy-to-world.html

https://oneprayer.org/banyacya_statement.html

https://oneprayer.org/History.html

***

The rattle shown above is similar to figure 256 in The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson. It came from the Hopi town of Walpi, Arizona, and was acquired by the Smithsonian museum around 1879.

Artifact is catalog number E42042-0 in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collections.

https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/anth/

It is described in:

James Stevenson (1883). Illustrated Catalogue of the Collections Obtained from the Indians of New Mexico and Arizona in 1879. Second Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1880-81. Page 394, figure 562.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu218801882smit/page/394/mode/2up

"In the Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology for the year 1880-81 (p. 394, fig. 562) is described a dance rattle made from a small gourd, ornamented in black, white, and red (fig. 256). The gourd has a Swastika on each side, with the ends bent, not square... The U.S. National Museum possesses a large number of these dance rattles with Swastikas on their sides, obtained from the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico and Arizona. Some of them have the natural neck for a handle, as shown in the cut; others are without neck, and have a wooden stick inserted and passed through for a handle. Beans, pebbles, or similar objects are inside, and the shaking of the machine makes a rattling noise which marks time for the dance." - Thomas Wilson (1898)

Hopi rattle, purchased by the Penn Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1931. Both sides have a swastika (see link for another photo). Object number 31-23-96, URL identifier 274963.

https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/274963

"Aya

This katcina appears in pairs in the Wawac, or Racing Katcina, and is readily recognized by the rattle (aya), which has swastika decorations on both sides, forming the head. The snout is seen in the blue projection near the left hand.

Aya wears the belt in a peculiar way, the ends hanging in front and behind, not on one side as is usually the case.

The red objects above the pictures represent rolls of paper-bread, the prizes in the races."

Illustration above published in:

Jesse Walter Fewkes. (1904). Hopi Katcinas Drawn by Native Artists. Extract from the 21st Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington: Government Printing Office. Plate L (50), Page 114.

https://archive.org/details/cu31924104075365/page/n213/mode/2up

Originally published in the following publication, although the scan below omits page 114.

Twenty-First Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1899-1900. (1903).

https://archive.org/details/hopikatcinasdraw00fewk/page/n5/mode/2up

Manuscript 4731, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution. Local Numbers: NAA INV 08547426 NAA MS 4731.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/ead_component:sova-naa-ms4731-ref137

***

If the same design continues onto the part that is not visible, it is a swastika.

"Protohistoric Hopi" ladle, Pueblo IV period (1350-1600 AD), Koo-Uy-Kah, Arizona. Object number 39010, URL identifier 221306 in the collection of the Penn Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/221306

***

In the following encyclopedia,[11] it says the swastika is a geographic representation of the Hopi migration myths of their ancestors.[11] It suggests that these myths indicate the ancestors of the Hopi migrated from South America before arriving in the Southwest,[12] perhaps bringing the swastika with them on their migrations. I have also heard it described that sometimes the Hopi use a swastika with only three hooks to represent their migration legends. However, Hopi elder Thomas Banyacya (see above) describes the swastika as a sun symbol, so the precise meaning of the Hopi swastika likely depends on the context.

I decided to dig a bit deeper into the sources quoted by the encyclopedia. Alexander M. Stephen lived in the Southwest from the 1880s until his death in 1894, and wrote detailed ethnographic accounts of the Navajo and Hopi peoples.[13] He reported that the swastika symbol found on the aya rattles is called "ai'veni".[14] Stephen also spoke to Pauwati'wa, Hopi leader of the Reed clan of the Goat kiva,[15] who suggested that the swastika was derived from the nakwách symbol, which represents brotherhood or friendship.[14]

The encyclopedia[11] also includes a rock art swastika in this section, which is similar in design to the ladle above.

"Petroglyph, Paiute Creek mouth, Glen canyon area, Utah.

Style 4 design. Informant recognition: The spiral ended swastika is a symbol meaning friendly or peace making.

[Redrawn from Turner 1963:49]"

I am unable to find the book/article by Turner.

Maricopa (Piipaash)

The Maricopa (Piipaash) people live in southern Arizona, surrounding the Phoenix metropolitan region in the Gila River Indian Community and Salt River Pima–Maricopa Indian Community reservations.

According to Wikipedia, the Maricopa living in the Gila River Indian Community live in "Maricopa Colony" or "Maricopa Village", which is a small village close to the Estrella and Laveen neighborhoods in the Phoenix area.

There is also the city of Maricopa, Arizona, which borders the Ak Chin Indian Community of the Maricopa (Ak-Chin) Indian Reservation. The Ak-Chin Community is headquartered in the city of Maricopa. However, they only became a federally-recognized tribe in 1961, and the primary inhabitants are Akimel O'odham (Pima) and Tohono O'odham ("Papago"), rather than the Maricopa people.

Anthropologists believe present-day cultures such as the Maricopa, Yavapai, and Quechan (Yuma) are the descendants of the Patayan culture, who also used the swastika.

This showed up in the search results as being listed on Etsy and Ebay, but it seems to have been sold and the pages are now 404'd and not captured by the Internet Archive Wayback Machine. The image url still works, however.

https://www.etsy.com/listing/631228391/rare-late-19th-c-maricopa-wedding-vase-4

https://www.ebay.com/itm/RARE-LATE-19TH-c-Maricopa-Wedding-Vase-4-Sacred-Direction-Swastika-Design-6-5-H-/113024385471

https://i.etsystatic.com/17173697/r/il/90b363/1616943389/il_794xN.1616943389_abzo.jpg

The title of this piece is labelled as "Maricopa Wedding Vase, ca. 19th Century", but the description says it's from the 1930s. Item #1111 in the collection of CulturalPatina, owned by Dennis Brining of Virginia.

https://www.etsy.com/listing/520514926/vintage-maricopa-wedding-vase-ca-19th

https://i.etsystatic.com/9473711/r/il/2bc342/1211817596/il_1140xN.1211817596_e4a7.jpg

Maricopa pottery bowl, by Susie Bill, ca. 1930s-1940s. Item #1424 in the collection of CulturalPatina, owned by Dennis Brining of Virginia.

https://www.culturalpatina.com/products/native-american-vintage-maricopa-pottery-bowl-by-suzie-bill-ca-1940s-1424

Maricopa pottery bowl, by Lula Young, ca. 1930s-1940s. Item #1124 in the collection of CulturalPatina, now sold to a collector.

https://www.culturalpatina.com/products/native-american-maricopa-poly-chrome-pottery-bowl-by-lula-young-ca-1940s-1124

Description: "9N Maricopa Polychrome Olla". Date unknown, perhaps from the 1930s-1940s. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20160623064200/http://rarepottery.info/protect/MaricopaUnsigned.htm

Description: "18N Maricopa Black-on-Red". Date unknown, perhaps from the 1930s-1940s. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20160623064200/http://rarepottery.info/protect/MaricopaUnsigned.htm

Description: "20N Maricopa Black-on-Red". Date unknown, perhaps from the 1930s-1940s. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20160623064200/http://rarepottery.info/protect/MaricopaUnsigned.htm

Navajo

The Navajo people are the largest federally-recognized Native American nation in the United States and have the largest reservation--which is located primarily in Arizona.

The Navajo are closely related to the Apache peoples, and migrated to the Southwest around the same time period. Historically nomadic hunter-gatherers, they arrived in the region by 1400 AD and moved into the area which had been vacated by the Ancestral Puebloans.

Sand painting is an important custom in Navajo culture. The sand paintings can be used as a device to tell the story of different myths, legends, and matters of spiritual importance. One common legend found in Navajo sand paintings is the Whirling Log. The whirling log motif consists of a cross (the logs) with gods or human figures standing on the ends, giving four-fold rotational symmetry in the style of a swastika.

It appears that people on the internet also refer to "standard" swastikas used by the Navajo (卐 and 卍) as whirling logs, but it is unclear to me if the "standard" swastikas are also considered a representation of the whirling log myth, or should be considered a separate symbol. Some people also refer to all US Native American swastikas as whirling logs, but this should not be considered accurate.

James Stevenson. (1891). Ceremonial of Hasjelti Dailjis and Mythical Painting of the Navajo Indians. Eighth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1886-87. Page 229-285. See page 262, plate CXXI. Page 261-263 explains the story behind this sand painting.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu818861887smit/page/n609/mode/2up

The Navajo have other sand paintings in the shape of swastikas, such as the Whirling Rainbow, suggesting it is inaccurate to refer to all Navajo swastikas as whirling logs.

Whirling Rainbow - Navajo sand painting by Nelson J. Cambridge. Photo of the art published online in:

Steven McFadden. (2006). Odyssey of the 8th Fire. Day 35.

https://www.8thfire.net/Day_35.html

In The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson, Wilson describes at great length a Navajo myth which is accompanied by a sand painting in his Plate 17. The image above is the full color version of the plate from the original source. To read the full description of the myth in Wilson's work, click here:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html#Navajoes

The original source of this illustration is below:

Washington Matthews. (1887). The Mountain Chant: A Navajo Ceremony. Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1883-84. page 385-467. See page 450 for plate 17.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu518831884smit/page/n545/mode/2up

***

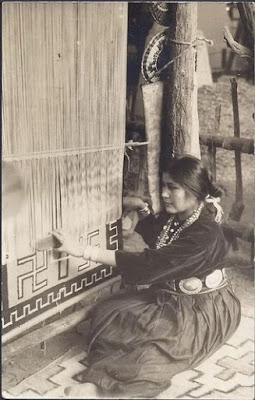

The type of art that the Navajos are perhaps most famous for are their rugs and textiles. Demand for these textiles was driven by "white" merchants in the late 1800s and early 1900s. "Authentic" Navajo rugs from this period are today considered a coveted collector's item among yuppies. "Standard" swastikas are a common symbol on these rugs.

John Bradford Moore (1855-1926) was a "white" man who set up a business in Crystal, New Mexico in the 1890s to 1910s in order to sell Native American goods to consumers in the US. His mail-order catalog gained a large following in the US. Apparently he designed many of his "Navajo rug" patterns himself and had his weavers mass produce these patterns for commercial sale.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Bradford_Moore

Navajo rug, "JB Moore Crystal Storm No. A75", ca. 1909-1920. Rug said to be made by "Dug-gau-eth-Ion bi Dazhie or a member of her weaving family." Exhibited at "The Navajo Rug" exhibition at Kings Art Center in Hanford, California, 2010. From the collection Charley and Valerie Castles; rug sold to a collector.

https://charleysnavajorugs.com/navajo-rug-exhibits/

J.B. Moore Navajo textile, 1920s. Item #1002a in the collection of CulturalPatina, owned by Dennis Brining of Virginia.

https://www.etsy.com/listing/474516170/native-american-historic-j-b-moore

There are many additional examples of J.B. Moore rugs with swastikas on them. I wonder if his company was one of the ones to compel Southwestern Native Americans to sign the 1940 declaration against the swastika? A few additional examples of his rugs can be seen below:

Navajo rug, ca. 1900-1920, catalog number 1986.847 in the Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RugNavajo-BMA.jpg

https://www.artsbma.org/collection/rug-early-crystal-style/

Navajo rug, ca. 1900-1920, catalog number 1986.853 in the Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama.

https://www.artsbma.org/collection/rug-early-crystal-style-2/

Akimel O'odham (Pima)

The Akimel O'odham ("river people") live in southwestern Arizona, and were historically called Pima by Spanish and US colonists.

Archaeologists believe they, and other O'odham-speaking peoples, are descended from the Hohokam culture, who lived in the same general area in Arizona.

Owl pot. Date unknown, perhaps from the 1930s-1940s. A similar owl pot is listed as having been purchased from the "Pima Indian Reservation" in 1935-1936. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20160623064200/http://rarepottery.info/protect/MaricopaUnsigned.htm

Basket, ca. pre-1939, in the collection of the California State Parks Museum collections. Object number 498-42-5.

http://www.museumcollections.parks.ca.gov/code/emuseum.asp

Figure 258 in The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson, shows a "Pima war shield" with a swastika painted on it. At the time, it was owned by Mr. F. W. Hodge, of the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian Museum.

See the following link to read Wilson's description of it:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html#Pimas

Bowl from Arizona. Date unknown, gifted to the museum in 1938. In the collection of the Penn Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Object number 38-27-90, URL identifier 251044.

https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/251044

***

Note the similarity between the following swirling swastika designs on these baskets and the swirls found on Nodena Mississippian pottery.

Basket with two types of stylized swastikas, Arizona. Date unknown. In the collection of the Penn Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Object number 38-27-24, URL identifier 374594.

https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/374594

Basket, ca. 1890. Catalog number BA-0304 in the Morning Star Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

https://www.morningstargallery.com/basketry/newitem-kt6gh

Tohono O'odham ("Papago")

The Tohono O'odham ("desert people") live to the south of the Akimel O'odham in an arid portion of Arizona. Historically, they were called "Papago" by Spanish and US colonists, although today many reject this name.

Archaeologists believe they, and other O'odham-speaking peoples, are descended from the Hohokam culture, who lived in the same general area in Arizona.

Tohono O'odham polychrome pottery, ca. 1930s-1940s. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20180409130825/http://rarepottery.info/protect/PapagoPottery.htm

Tohono O'odham woven basket, south/southwest of Tucson, Arizona, ca. early 1900s. Catalog number CAS 0145-0005 in the collection of California Academy of Sciences (CAS), San Francisco, California.

https://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/anthropology/collections/Index.asp

Quechan (Yuma)

Today the Quechan (Yuma) people live in the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation, in the southwestern corner of Arizona and southeastern corner of California along the Colorado River.

Anthropologists believe present-day cultures such as the Quechan, Yavapai, and Maricopa (Piipaash) are the descendants of the Patayan culture, who also used the swastika.

Description: "7N Yuman Black-on-Red Wedding Vase." Date unknown. Photo from the website RarePotteryInfo.

https://web.archive.org/web/20161107020354/http://rarepottery.info/protect/YumanPottery.htm

Yavapai

The Yavapai people live in west-central Arizona.

Anthropologists believe present-day cultures such as the Yavapai, Maricopa (Piipaash), and Quechan (Yuma) are the descendants of the Patayan culture, who also used the swastika.

Yavapai basket, early 20th century. Accession number 1939.371 in the collection of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Yavapai_p1070211.jpg

https://cantorcollection.stanford.edu/objects-1/info

Zia

The Zia people are a Puebloan culture who live at Zia Pueblo (Tsi'ya) in New Mexico. The Zia are most noted for their solar symbol which was incorporated into the flag of New Mexico.

Zia pottery jar, ca. 1910. Item #1251 in the collection of CulturalPatina, owned by Dennis Brining of Virginia.

https://www.etsy.com/listing/572105091/native-american-historic-zia-poly-chrome

Native Americans elsewhere in the United States

Hopewell culture

The Hopewell culture was not a single nation of people, but is a term used to describe various archaeological sites which traded similar items and practiced some similar customs. It existed from around 100 BC to 500 AD in much of the Mississippi basin and Great Lakes regions. For thousands of years, the Hopewell culture's predecessors had been practicing agriculture. Specifically, the Eastern Agricultural Complex began intensive agricultural cultivation by at least 1800 BC in the Ohio River valley. Not surprisingly, the swastika can be found here as well.

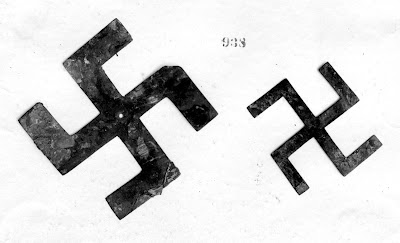

"Hopewell Green Slate Ceremonial Swastika", ca. 200 BC - 200 AD. In the collection of the Barakat Gallery, SKU PF.0335. Precise location where this artifact was found is not provided.

https://store.barakatgallery.com/product/hopewell-green-slate-ceremonial-swastika/

Presumably this is the same artifact. I am unable to find the original source of this photo.

The following are excerpts from The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson. To read the entire chapter in Wilson's work, see here:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html#PreColumbian

"Hopewell Mound, Chillicothe, Ross County, Ohio.—A later discovery of the Swastika belonging to the same period and the same general locality—that is, to the Ohio Valley—was that of Prof. Warren K. Moorehead, in the fall and winter of 1891-92, in his excavations of the Hopewell mound, seven miles northwest of Chillicothe, Ross County, Ohio.[254] The locality of this mound is well shown in Squier and Davis’s work on the “Monuments of the Mississippi Valley” (pl. 10, p. 26), under the name of “Clark’s Works,” here reproduced as pl. 11. ...[I]n opening trench 3, about five feet above the base of the mound, they struck a mass of thin worked copper objects, laid flat one atop the other, in a rectangular space, say three by four feet square. These objects are unique in American prehistoric archæology. ...

The following list of objects is given, to the end that the reader may see what was associated with these newly found copper Swastikas: Five Swastika crosses (fig. 244);"

[254] These explorations were made for the Department of Ethnology at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893.

- Thomas Wilson (1898)

Figure 241 in Wilson's work.

Other artifacts found at the site demonstrate a trade network of considerable distance. This suggests the swastika could very well have been diffused across the entire continent in pre-Columbian times.

"Evidence was found of an extended commerce with distant localities, so that if the Swastika existed in America it might be expected here. The principal objects were as follows: A number of large seashells (Fulgur) native to the southern Atlantic Coast 600 miles distant, many of them carved; several thousand pieces of mica from the mountains of Virginia or North Carolina, 200 or more miles distant; a thousand large blades of beautifully chipped objects in obsidian, which could not have been found nearer than the Rocky Mountains, 1,000 or 1,200 miles distant; four hundred pieces of wrought copper, believed to be from the Lake Superior region, 150 miles distant; fifty-three skeletons, the copper headdress (pl. 13) made in semblance of elk horns, 16 inches high, and other wonderful things. Those not described have no relation to the Swastika." - Thomas Wilson (1898)

The artifacts were excavated by Warren K. Moorehead during 1891-1892 at the Hopewell Mound Group near Chillicothe, Ross County, Ohio. The artifacts are housed in the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois. In 2015, the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, in collaboration with other institutions, began the Ohio Hopewell: Prehistoric Crossroads of the American Midwest project. They have photographed and provided a digital catalog of the Field Museum's Hopewell artifact collection.

http://hopewell.unl.edu/

http://hopewell.unl.edu/images.html

Wilson mentions five swastikas were found. However, this collection only has photos of two of them, one of which is Wilson's Fig. 244.

Item A110010 (catalog number 56204). Copper swastika. This is the figure published in Wilson's work.

See also this catalog number's listing in the Field Museum Anthropological Collections:

https://collections-anthropology.fieldmuseum.org/catalogue/1286768

Item A78501, an image showing 5 copper artifacts. The image includes a copper swastika (catalog number 56205), which is different from the one above.

Item A91000, a photograph of a display showing many different copper ornaments. The image includes both of the swastikas mentioned above.

See also the original photo albums of Hopewell Mounds. Specifically, Negative Numbers 938 and 78501 in Hopewell 44 and Negative Number 110010 in 44a.

http://hopewell.unl.edu/excavation_albums.html

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture proceeded the Hopewell culture in roughly the same geographic area, lasting from approximately 800 AD to 1600 AD.

This artifact appears as figure 237 in The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson. It is a carved shell gorget found at Fains (Faines) Island, Tennessee, near the town of Dandridge. Catalog number A62928-0 in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collections.

https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/anth/

Wilson writes:

"A specimen (fig. 237) was taken by Dr. Edward Palmer in the year 1881 from an ancient mound opened by him on Fains Island, 3 miles from Bainbridge, Jefferson County, Tenn. It is figured and described in the Third Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology..."[247]

[247] Page 436, fig. 140.

From the Third Annual Report mentioned above:

" MOUND ON FAIN'S ISLAND.

This mound is located on the east end of the island. Although it has been under cultivation for many years, it is still 10 feet in height. The circumference at the base is about 100 feet. Near the surface a bed of burned clay was encountered, in which were many impressions of poles, sticks, and grass. This was probably the remains of the roof of a house, which had been about 16 feet long by 15 feet in width. The bed of clay was about 4 inches thick. Beneath this was a layer of charcoal and ashes, with much charred cane. There were also indications of charred posts, which probably served as supports to the roof. Four feet below the surface were found the remains of thirty-two human skeletons. With the exception of seventeen skulls, none of the bones could be preserved. There seems to have been no regularity in the placing of the bodies.

William H. Holmes. (1884). Illustrated Catalogue of a Portion of the Collections Made by the Bureau of Ethnology During the Field Season of 1881. Third Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1881-82. Page 427-510. See page 466 for Fig. 140

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu318811882smit/page/466/mode/2up

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19416/19416-h/19416-h.htm

I am unable to find more information regarding the date of this artifact. A later excavation on the island took place in the 1930s, classifying the site as part of the Dallas Phase Mississippian (ca. 1300-1600 AD).[16] During this time period, the site was near the Native American city of Chiaha, which appears to have been a principality under the influence of the large Coosa kingdom. In the 1940s, a dam was constructed and submerged the island.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dallas_Phase

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chiaha

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coosa_chiefdom

Here is an article behind a paywall about Edward Palmer, who excavated the site:

Marvin D. Jeter. (1999). Edward Palmer: Present before the Creation of Archaeological Stratigraphy and Associations, Formation Processes, and Ethnographic Analogy. Journal of the Southwest Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 335-358.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40170103

Description: "Nashville II style shell gorget from Chickamauga Creek in the Chattanooga area of Hamilton County, Tennessee." I don't know which museum has this artifact.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nashville_II_style_gorget_HRoe_2012.jpg

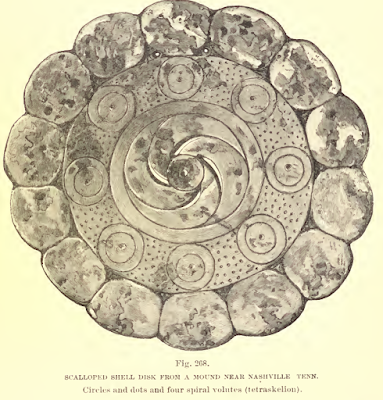

Figures 268 and 269, in The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson. See below to read a full description of them:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html#EngravingsPaintings

Wilson's figure 268. Found near Nashville, Tennessee. Wilson says it is in the collection of the Peabody Museum, Yale University. I searched their collections online and didn't seem to see the artifact.

Artifact first described in the following publication:

Second Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1880-81. Edited by J. W. Powell. Washington: Government Printing Office. (1883). Page 276, plate 55.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu218801882smit/page/276/mode/2up

Artifact first described in the following publication:

Second Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1880-81. Edited by J. W. Powell. Washington: Government Printing Office. (1883). Page 276, plate 55.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu218801882smit/page/276/mode/2up

***

Shell gorgets found at the Spiro Mounds site, Oklahoma. The mound was plundered by grave robbers in the 1930s, so many artifacts and their original contexts have been lost. The site at Spiro dates to around 900-1450 AD.

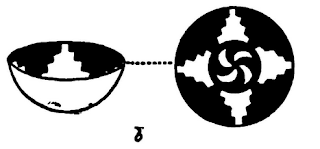

Gorgets found in Craig Mound, Spiro. Two dancers with swastika in the center (left) and four birds arranged in a swastika-like pattern with a swastika carved in the center (top-right). I have sometimes seen the birds called a "Sunbird Swastika" on the internet, although I don't know if that's what archaeologists call it. Artifacts in the collection of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma

https://texasbeyondhistory.net/tejas/fundamentals/images/spiro_gorgets.html

Clearer photo of the dancing twins artifact, showing the swastika.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Craig_C_style_shell_gorget_Spiro_HRoe_2005.jpg

The following link shows a replica of the artifact in the Spiro Mounds interpretive center, at the site of the mounds in LeFlore County, Oklahoma. Artifact is from Burial 108, Craig Mound, ca. 1200-1350 AD.

https://web.archive.org/web/20140707065650/http://oklahomahomeschool.com/FTCSpiro.html

Someone also made a colored version of this artifact. I don't know if the colors should be considered accurate or not.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:S.E.C.C._hero_twins_3_HRoe_2007-transparent.png

Replica of a Craig Mound-style gorget from Spiro. Spider with swastika. In the collection of the Woolaroc Museum, Barnsdall, Oklahoma.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Replica_Craig_style_shell_Gorget_Woolaroc_1.jpg

Craig Mound-style gorget with concentric circles of hands surrounding a swastika, ca. 1200-1450 AD. In the collection of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma.

https://spiromounds.com/collection/objects/engraved-shell-gorget-with-human-hands-

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/850195235876654624/

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/9e/02/4e/9e024eb13b06c8b52417e99fff7c69fc.jpg

Joan S. Gardner. (1980). The Conservation of Fragile Specimens from the Spiro Mound, LeFlore County, Oklahoma. Contributions from the Stovall Museum, University of Oklahoma, No. 5.

https://samnoblemuseum.ou.edu/publications/jean-s-gardner-the-conservation-of-fragile-specimens-from-the-spiro-mound-le-flore-county-oklahoma/

Mississippian culture, Nodena phase

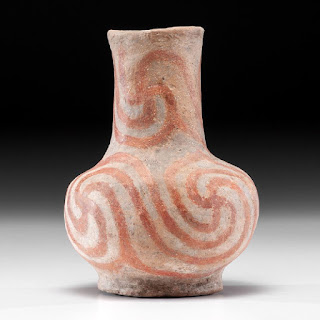

Another common motif in Mississippian art is large intersecting whirls. Many of these have four "arms" in the style of a swastika. Others have 3, 5, 6, or more. However, given the use of other types of swastikas in Mississippian culture, in addition to the high frequency of the four-armed whirls, it is probably reasonable to consider this design to be a variant of a swastika.

Specifically, these designs are found on pottery and associated most strongly with the Nodena Phase of Mississippian culture. The Nodena Phase was an archaeological period that existed around 1400-1650 AD along the Mississippi River in Arkansas and parts of Missouri.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nodena_Phase

Recall that a similar swastika whirl design is found in Akimel O'odham (Pima) baskets. For example, click here to go back to the previous section to see an example of these baskets. Note especially how in both the Akimel O'odham design and Mississippian design below, the swastika has a hole where the lines intersect.

Nodena bottle, in the collection of the Hampson Museum State Park in Wilson, Arkansas. Hampton ID: LR_41635, Ark Hm 401.

https://hampson.cast.uark.edu/view/2

Photo published by Dr. Michael Fuller:

https://users.stlcc.edu/mfuller/NodenaPotteryPaint.html

Nodena bottle, Arkansas, ca. 1000-1500 AD. From the Jack Roberts Collection, Tunica, Mississippi. Sold at auction by Cowan's Auctions, 2018, lot 0079 item 66588710.

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/66588710_a-nodena-swirl-water-bottle-9-12-x-6-14-in

Description: "Mississippian bottle with a Nodena swirl design. ... Personal find of R. W. Lyerly in Poinsett County, Arkansas."

Description: "Mississippian Nodena swirl design bottle found by R. W. Lyerly in Poinsett County, Arkansas."

The two images above were published on the Central States Archaeological Societies (CSASI) website, from the Spring 2003 journal (Volume 50, No. 2).

https://csasi.org/2003_spring_journal/2003_selected_pictures_from_the_spring_journal.htm

Figures 289, 290, and 294 in The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson, describe Nodena ceramics. See the excerpt from his book where he describes these artifacts:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html#NativeAmericanPottery

The artifact above was first described in the publication below:

William H. Holmes. (1886). Ancient Pottery of the Mississippi Valley. Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1882-83. Edited by J. W. Powell. Washington: Government Printing Office. Page 403, fig. 413.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu418821883smit/page/402/mode/2up

The artifact above was first described in the publication below:

William H. Holmes. (1886). Ancient Pottery of the Mississippi Valley. Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1882-83. Edited by J. W. Powell. Washington: Government Printing Office. Page 404, fig. 415.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu418821883smit/page/402/mode/2up

The artifact above was first described in the publication below:

William H. Holmes. (1886). Ancient Pottery of the Mississippi Valley. Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution: 1882-83. Edited by J. W. Powell. Washington: Government Printing Office. Page 421, fig. 442.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbu418821883smit/page/402/mode/2up

***

In 1897 Charles Clark Willoughby published an article with many small illustrations of Mississippian pottery, many of which had swastikas. Willoughby extensively cites artifacts from the Peabody Museum. There is a Peabody Museum at Yale University and one at Harvard University. Willoughby spent many decades employed at Harvard's Peabody Museum, and we may therefore assume the artifacts came from their collections.

Images are from the following article:

Charles Clark Willoughby. (January - March 1897). An Analysis of the decorations upon Pottery from the Mississippi Valley. Journal of American Folk-Lore, 10(36): 9-20.

https://archive.org/details/prehistoricarto00uphagoog/page/n519/mode/2up

Fig 11a in Willougby (1897). Vase from Missouri. In the collection of "St. Louis Academy." (Presumably this is The Academy of Science – St. Louis. The Saint Louis Science Center was founded by The Academy and presumably has the artifact in their large archaeological collection today.)

Figure 12b in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Bowl decorated with terraced figures and swastika, symbols of the clouds and the four winds. Arkansas." In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

,%20figure%2014a-f.PNG)

Figure 14b in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Bowl decorated with symbol of the four winds." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 14c in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Bottom of vase with swastika decoration." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 14d in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Bottom of vase with swastika decoration." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 14e in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Bowls with symbol of the four winds or swastika." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 14f in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Bowls with symbol of the four winds or swastika." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

,%20figure%2015a-b.PNG)

Figure 15a and b in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Vase decorated with three swastikas, the ends of some of the arms of the crosses being curved to fill the blank space on vase." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

,%20figure%2016a-c.PNG)

Figure 16a, b, and c in Willoughby (1897). Description: "a. Vase with swastika decorations, the ends of the arms of the crosses being joined; b. Vase seen from below, showing sun disk and cruciform figure formed by the lower arms of the swastikas; c. Design encircling the vase." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Perhaps object number 80-20-10/22038 in the Peabody Museum, Harvard University. Parkin Phase of the Mississippian culture, 1350 - 1550 AD. Artifact from Rose Mound; Arkansas State # 3CS27. Wittsburg, Arkansas.

https://collections.peabody.harvard.edu/objects/details/128739?ctx=c59c401bdcce3e0b1a3e73a9233a24fdef4bd60b&idx=280

,%20figure%2017a-e.PNG)

Figure 17a in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Vases decorated with joined swastikas and other designs." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 17b in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Vases decorated with joined swastikas and other designs." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 17c in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Vases decorated with joined swastikas and other designs." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 17d in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Vases decorated with joined swastikas and other designs. Upon the neck of d four terraced cloud figures are painted, and the legs of the vessel are also terraced." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Figure 17e in Willoughby (1897). Description: "Vases decorated with joined swastikas and other designs." Arkansas. In the collection of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Cahuilla

The Cahuilla people have lived in southern California since at least the early 1700s.

Bowl from Cahuilla, California. Catalog number YPM ANT 148132 in the Yale Peabody Museum.

https://collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Record/YPM-ANT-148132

Delaware (Lenape)

Historically, the Lenape people lived in an area corresponding to present-day New Jersey, northern Delaware, eastern Pennsylvania, and southern New York. By the late 1700s, they had been expelled westward, and in the 1800s they were expelled multiple times before reaching Oklahoma by the mid-1800s.

Delaware culture tobacco pipe bag. Date unknown.

State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Photo by Esteban Cavrico.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/36179943@N00/42460850/

Judging by the horse shoes on the bottom of the bag, maybe both they and the swastika are generic post-1870s "good luck" symbols?

Kaw (Kanza/Kansa)

The oral history of the Kaw (Kanza) people suggests they migrated from somewhere in the Ohio River basin and reached the northeastern portion of Kansas by the mid-1600s. By the 1870s they had been forcibly moved to Oklahoma.

Figure 255 in The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson, shows a Kaw nation war chart described by J. Owen Dorsey in 1885. Dorsey reports that the Kaw war leader had told him the symbol was in use for many generations.

J. Owen Dorsey. (July 1885). Mourning and War Customs of the Kansas. The American Naturalist, Vol. 19, No. 7, page 670-680.

See Plate XX after page 676 for the war chart.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2450101

To read Wilson's commentary about this artifact, click here:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html#Kansas

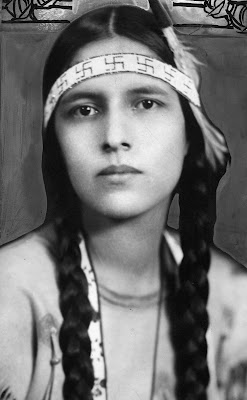

Lakota (Teton Sioux)

By the 1600s-1700s the Lakota people inhabited the regions of North and South Dakota.

Photo of Rosebud Yellow Robe (1907-1992), ca. 1927. She was a folklorist born on the Rosebud Indian Reservation of South Dakota, which belongs to the Sičháŋǧu Oyáte Lakota nation (also called Sicangu and Brulé), a sub-group of the Lakota people.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosebud_Yellow_Robe

Photo in the Denver Public Library Special Collections. Call number X-31841, CONTENTdm number 31983.

https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/31983

Lakota culture pipe and tobacco pouch, ca. 1900. In the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. Accession number 305336, USNM number E415796-0.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmnhanthropology_8447135

Mashpee Wampanoag

The Mashpee Wampanoag are a branch of the historic Wampanoag Confederacy who continue to live in southeastern Massachusetts.

Image cropped from a portrait of Mashpee Wampanoag members from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, 1929.

Photo in the Leslie Jones Collection, Boston Public Library.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/6378433417/in/album-72157628085309273/

Meskwaki (Fox)

Around the 1600s, the Meskwaki (Fox) people lived along the St. Lawrence River in Ontario. Over centuries of warfare with other Native peoples and colonial powers, they moved to Michigan, Illinois, and were later forcibly moved to Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. Since at least the early 1700s, the Meskwaki have been closely associaed with the Sac (Sauk) people.

Meskwaki (Fox) beaded vest, c. 1925. Iowa. In the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jondresner/4376997869/in/gallery-iamcosmos-72157708429063185/

Nanticoke

The Nanticoke people historically lived in the region around Delaware and Maryland.

Jane Harmon (or Janie Harman), photographed in Millsboro, Delaware, 1922. Photos in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. Frank Gouldsmith Speck photograph collection / Series 8: Delaware: Nanticoke and Rappahannock.

Image identifier NMAI.AC.001.032, Item N12470.

https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/components/sova-nmai-ac-001-032-ref1019

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/ead_component:sova-nmai-ac-001-032-ref1019

Jane Harmon (left) with Mohegan woman Gladys Tantaquidgeon, assistant to Frank Gouldsmith Speck (the photographer), 1922.

Image identifier NMAI.AC.001.032, Item N12475.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/ead_component:sova-nmai-ac-001-032-ref1024

See additional photos:

Image identifier NMAI.AC.001.032, Item N12477.

https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/components/sova-nmai-ac-001-032-ref1026

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/ead_component:sova-nmai-ac-001-032-ref1026

Image identifier NMAI.AC.001.032, Item N12479.

https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/components/sova-nmai-ac-001-032-ref1028

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/ead_component:sova-nmai-ac-001-032-ref1028

Nez Perce (Nimíipuu)

The Nez Perce (Nimíipuu) historically lived in the Columbia Plateau region in present-day Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

War Bonnet with swastikas on the sides. Date unknown. In the collection of the Nez Perce National Historical Park Museum, Spalding, Idaho. Catalog number NEPE 2225.

https://web.archive.org/web/20190713131225/https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/nepe/exb/dailylife/GenderRoles/NEPE2225-2226(2)_Head-dress.html

Belt pouch, made by Jennie Dickson, ca. 1915. In the collection of the Nez Perce National Historical Park Museum, Spalding, Idaho. Catalog number NEPE 6990.

https://web.archive.org/web/20190713131821/https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/nepe/exb/Special%20Feature_Textiles/NEPE6990_Bag.html

In addition, there is "Swastika Trail #233" and "Swastika Road #222-D" in the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forests, located near Elk City, Idaho. Although it is unclear if the names came from the Nez Perce use of the swastika, or the pre-WWII swastika craze among Anglo-Americans.

Ojibwe (Chippewa)

The Ojibwe people historically lived along the entire span of the northern portion of the Great Lakes in the US and Canada.

John Smith (1820s-1922), who lived near the Cass Lake, Minnesota, area. Due to his skin disease, photographers falsely claimed he was well-over 120 years old. I am unable to find more info on the date or original photographer of this image.

Osage

By the 1800s, the Osage had migrated to the northeastern corner of Oklahoma, near where their current reservation is.

Peter Bigheart, leader of the Osage Nation, wearing a swastika lapel, 1909.

Photo by William J. Boag. In the collection of the Gilcrease Museum/The University of Tulsa, Accession Number 4327.5813.

https://collections.gilcrease.org/object/43275813

Another print of this photo, in the Library of Congress. Library of Congress Control Number 97512111, Digital Id cph 3c19215.

https://www.loc.gov/item/97512111/

Another photo of Bigheart from the same session:

In the collection of the Gilcrease Museum/The University of Tulsa, Accession Number 4327.4407.

https://collections.gilcrease.org/object/43274407-0

***

"Asked if the sign was common and to be seen in other cases or places, Mr. Dorsey replied that the Osage have a similar chart with the same and many other signs or pictographs—over a hundred—but except these, he knows of no similar signs." -Thomas Wilson, The Swastika (1898).

He is referring to a similarity with the Kaw war chart.

Passamaquoddy

The Passamaquoddy people historically lived in the areas of New Brunswick, Canada, and Maine, USA.

In the 1920s, many photos were taken of William Neptune, leader (Governor) of the Passamaquoddy nation of the Pleasant Point Reservation, Maine.

Governor Neptune in Boston, 1921.

Photo in the Leslie Jones Collection, Boston Public Library.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/6378437437/

Additional photos from the Boston Public Library:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/6378431645/in/album-72157628085309273/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/6378433625/in/album-72157628085309273/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/6378440191/in/album-72157628085309273/

The following 2 pictures might also be Neptune (farthest right):

https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/6378434097/in/album-72157628085309273/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/6378437531/in/photostream/

Photo allegedly from 1920, original source is not provided.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Neptune,_Passamaquoddy_chief,_1920.jpg

Additional photos in the collection of the Maine Historical Society. 1920.

https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/23416

https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/23419

Pomo

The Pomo people historically lived in northern California along the coast and extending inland.

Pomo culture hat, northern California, ca. 1890s. Catalog number CAS 0129-0001 in the collection of California Academy of Sciences (CAS), San Francisco, California.

https://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/anthropology/collections/Index.asp

Potawatomi

In the 1600s, the Potawatomi lived in Michigan. In the early 1800s, they were forcibly moved to Kansas and Nebraska on the Trail of Death. A few decades later, they were forced to relocate to Oklahoma.

RoMere Darling (Martin) (1911-1979). She was a Potawatomi actress and community organizer. Photo believed to be from around 1950.

See more information about her, compiled by the blogger BrokenClaw, below:

https://web.archive.org/web/20160608021200/http://blog.brokenclaw.net/archives/romere-darling1

https://web.archive.org/web/20160608001532/http://blog.brokenclaw.net/archives/romere-darling2

https://web.archive.org/web/20160608042116/http://blog.brokenclaw.net/archives/romere-darling3

See also the section titled Kickapoo, Pottawatomie, and Iowa for a brief description of the swastika among these cultures (without any photos).

Sac (Sauk)

In the 1600s, the Sac (Sauk) people lived along the St. Lawrence River in northern New York. Over centuries of warfare with other Native peoples and colonial powers, they moved to Michigan, Illinois, and were later forcibly moved to Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. Since at least the early 1700s, the Sac have been closely associaed with the Meskwaki (Fox) people.

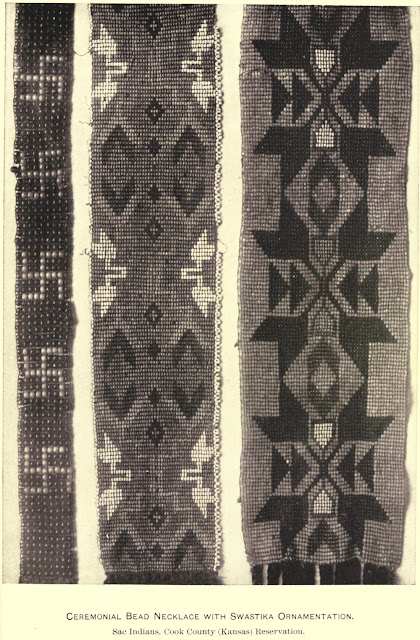

Plates 15 and 16 in The Swastika (1898), by Thomas Wilson, show beaded swastika necklaces and garters which were shown to Mary A. Owen by members of the Sac and Fox Reservation in Kansas. Owen says the Sac and related cultures are sun worshippers and they call the swastika "luck" or "good luck". She says the beadwork looked very well-worn and the Sacs told her they had "always" made swastika patterns in their beadwork, so it seems unlikely that it was derived from the post-1870s Western use of the swastika as a generic symbol of good luck.

For more information on these artifacts, click here:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html#Sacs

Secotan

The Secotans were one of the southeastern-most Algonquian peoples (inhabiting the eastern coastal region of North Carolina), and thereby culturally related to nations such as the Wampanoag and Passamaquoddy. They were ethnically cleansed by Western colonists by the late 1600s.

A swastika with small hooks was one of the symbols used to represent a clan, dynasty, or certain villages. Pomeiooc (Pomeyooc/Pamlico) and Aquascogoc were towns of the Secotan nation where this motif was used.

Swastika scarification marking or tattoo used in Pomeiooc and/or Aquascogoc. Illustration from Hariot's Narrative of The First Plantation of Virginia in 1585.

"The inhabitants of all the cuntrie for the most parte haue marks rased on their backs, whereby yt may be knowen what Princes subjects they bee, or of what place they haue their originall. [...] Those which haue the letters E. F. G. are certaine cheefe men of Pomeiooc, and Aquascogoc."

Thomas Hariot. (1st ed. 1588; illustrated ed. 1590). Hariot's Narrative of The First Plantation of Virginia in 1585. (1893). London: Bernard Quaritch. Plate XXIII.

https://archive.org/details/narrativefirste00harigoog/page/n132/mode/2up

Skokomish (Coast Salish)

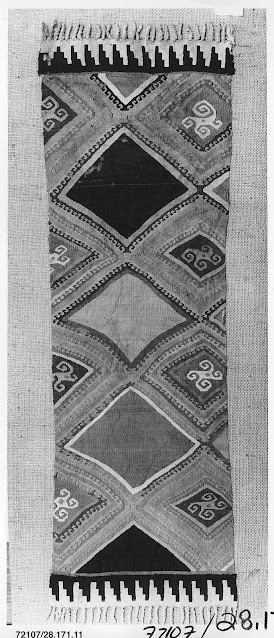

The Skokomish are a sub-group of the Twana, who have historically lived on the western coast of the Puget Sound in Washington state. The Twana are considered part of the "Coast Salish", a group of related ethnic groups who lived along the Puget Sound and coastal British Columbia.

Description: "This basket shows the four winds motif, symbolic of the power and strength of the wind. ... Since World War II, it has disappeared from all Coat Salish art."

Basket collected in 1916 on the Tulalip Reservation, Snohomish County, Washington. Catalog number 5/7926, barcode number 057926.000.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:NMAI_62495

Photo found on the following website, I am unable to find the original photographer:

https://web.archive.org/web/20190915055703/http://swastikaphobia.weebly.com/native-american.html

See this interview with Marilyn Jones, Skokomish community curator, describing the meaning of the Skokomish four winds swastika symbol. The basket was on display at the exhibition titled "Listening to Our Ancestors" at the National Museum of the American Indian, around 2013.

Uploaded to Youtube on March 13, 2013, by the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

https://learninglab.si.edu/resources/view/357925

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7dMJZbmGP8

Basket collected in 1916 on the Tulalip Reservation, Snohomish County, Washington. Catalog number 5/7890, barcode number 057890.000.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:NMAI_62459

In the previous image, the caption in the bottom-right describes this basket as Skokomish. On the Smithsonian collection's website, it says this artifact was collected from the Tulalip Reservation in Washington and labels it as being from the Twana culture. Twana is the collective name for nine Coast Salish nations in the Puget Sound region of Washington--which includes the Skokomish culture and Tulalip culture.

Tlingit

The Tlingit people historically lived along the Alexander Archipelago--the southeastern coastal region of Alaska.

Tlingit culture basket, southeast Alaska, donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1939. Accession number 153865, USNM number E379791-0.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:nmnhanthropology_8415615

Tlingit culture basket (Alaska?). Collected or donated to the museum in 1962. Catalog number 09160 in the Logan Museum of Anthropology, Beloit College Digital Collections.

https://dcms.beloit.edu/digital/collection/logan/id/3297

Caption: "Chilkat Blanket and Woman". (See the baskets).

Photo published in:

Livingston F. Jones. (1914). A Study of the Thlingets of Alaska. Fleming H. Revell Company. Page 168.

https://archive.org/details/cihm_74375/page/n197/mode/2up

According to Wikipedia, Chilkat weaving is a style of weaving practiced by the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian cultures, although the name originates from the Tlingit people of the Chilkat (Jilkháat) region.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chilkat_weaving

Wyam

The Wyam are a subgroup of the Tenino people, who historically inhabited the north-central area of Oregon.

Tommy Thompson was the leader of Celilo Village, Oregon, from the early 1900s until his death in 1959. Photo from 1935.

Photo in the Gerald W. Williams Collection at Oregon State University. Item number WilliamsG:NA_Thompson.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chief_Tommy_Thompson_at_Celilo_Falls,_Oregon_(3230030878).jpg

https://www.flickr.com/photos/34586311@N05/3230030878

https://oregondigital.org/sets/gwilliams/oregondigital:df66tv070

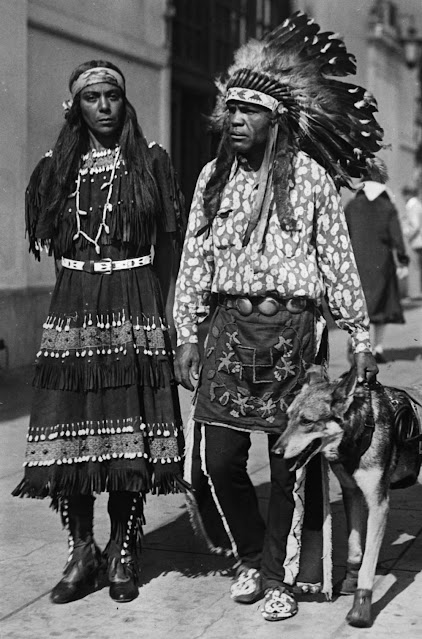

Yaqui

The Yaqui people historically lived in what is now northwestern Mexico and the southwestern United States.

Little Chief White Eagle (Bill Reed) on the right wearing a swastika. According to the caption, he is from California, although the Yaqui people are also found in the American Southwest and into Mexico. On the left is Princess Rainbow Sistesso, a Sioux woman and White Eagle's soon-to-be wife. October 1930.

Denver Public Library Special Collections. Call number X-31186, CONTENTdm number 23638.

https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/23638

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School

Chilocco Indian Agricultural School in northern Oklahoma operated as a Native American boarding school from 1884 to 1980. Students of many different nations attended the school, including Cherokee, Choctaw, Navajo, Creek, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Wichita, Comanche, and Pawnee. On some of the school's sports uniforms, they used swastikas.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chilocco_Indian_Agricultural_School

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Indian_boarding_schools

Chilocco Indian School basketball team, 1909. Photo in the collection of the US National Archives, identifier number 251717.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basketball_team_on_Home_1_Steps,_1909_-_NARA_-_251717.tif

Chilocco Indian School basketball team, 1909. Photo in the collection of the US National Archives, identifier number 251737.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Basketball_Team,_Standing_1909_-_NARA_-_251737.jpg