This article is part of a series examining the use of the swastika worldwide. With this project, we will once and for all demonstrate that the swastika is a world-wide symbol to which Neo-Nazis and other tribalists have no claim.

This page contains over 150 examples of swastikas throughout the history of China, Tibet, Japan, the Koreas, and Mongolia.* It is not an exhaustive attempt to collect every swastika known from these nations, but is intended to show how the swastika has been used for thousands of years in these regions.

The earliest known swastikas in this region are found in the Majiayao culture of China, around 2700-2350 BC. It's unclear if the swastika continued to be used immediately after the end of the Majiayao. Rock carvings of swastikas dating back to the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age (c. 1000-700 BC) are found in Tibet. These may have been influenced by diffusion of the swastika during the Vedic period of India, or perhaps transmitted through the same trade networks north of the Himalayas which had brought the swastika to the Majiayao a millennium prior. Beyond the Himalayas, the symbol appears again as a representation of a specific comet by 200 BC.

By the 400s AD, Buddhism had become a popular religion among Chinese royalty and commoners, likely re-popularizing the swastika. Over the next few hundred years, Buddhism spread to Korea, Japan, and Tibet, spreading the swastika—perhaps for the first time in some of these areas. Around 1000 AD, the Tibetan indigenous religion of Bon transformed into a form called Yungdrung Bon. Yungdrung means swastika, and swastikas are given numerous sacred meanings in Yungdrung Bon.

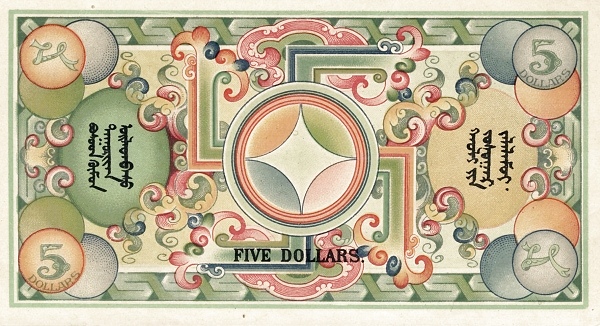

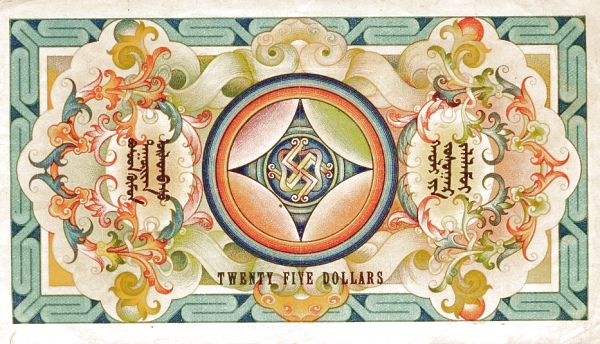

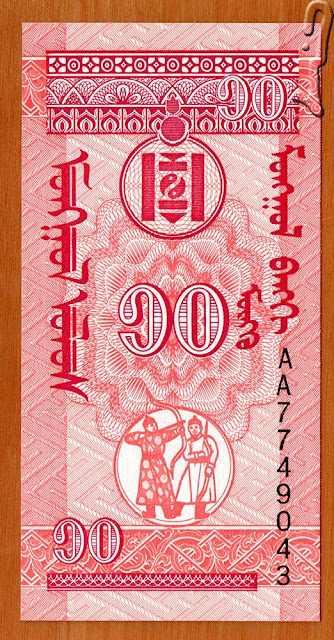

In the late 1200s AD, the Mongol Emperor and many of his subjects converted to Buddhism, spreading the swastika throughout Mongol culture, if it had not already been present. Forms of the swastika were used as part of the state seal, and the swastika continues to be used in official Mongolian state emblems to this day. In addition, during the Yuan dynasty period of Mongol rule in China, Nestorian Christians frequently used the swastika on metal emblems. It is unclear if this is a syncretic incorporation of the Buddhist swastika, or if the Nestorians were one of the many Christian groups to use the swastika as a variant of the Christian cross. The swastika's popularity in Mongolia was so high that even communists and anti-communists used it as an emblem in the 1920s.

Around the same time the swastika was becoming popular in Mongolia, in Japan we find evidence of the swastika becoming a clan emblem in a number of different forms. The swastika continues to be used as the official emblem of some cities as a legacy of these clans. In the Qing dynasty period of China, the swastika became a common symbol on rank badges worn by imperial officials.

In these cultures, the swastika also became a common ornament on clothing, architecture, and other items. It continues to be associated with Buddhism, Bon, Xiantiandao, Shinto, and other religions. In Japan, manji (swastika) even become a popular youth slang in the 2010s.

Throughout history, cultures, and religions, we find examples of right-facing, left-facing, and rotated swastikas. You now have the duty to correct people when they repeat the misconception that there is some universal difference based on a swastika's orientation.

* Although "East Asia" is a Eurocentric term, we unfortunately use it in this article for the sake of convenience.

If you have other examples of swastikas from these countries (especially of ancient swastikas), we encourage you to share on this article's discussion page:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/2023/12/swastikas-in-east-asia-discussion-post.html

Map showing the approximate locations of the artifacts mentioned in the article. Note that many artifacts on this page don't have a specific location associated with them.

To return to the index of swastika articles, click here.

Table of Contents

- Swastikas in China

- Summary

- Majiayao culture

- Representation of a comet

- As a Buddhist symbol

- The swastika as a Nestorian Christian symbol

- As a symbol in other religions

- Chinese coins

- Geometric fret design with connected swastikas

- Shou character

- Chinese rank badges (mandarin squares)

- Other and general examples in China

- Swastikas in Taiwan

- Swastikas in Tibet

- Swastikas in Japan

- Swastikas in Korea

- Swastikas in Mongolia and Mongol culture

- Western prejudice against the swastika in China, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia

- Index of Names and Meanings of the Swastika

- Footnotes

Swastikas in China

Summary

The swastika first appears in China in the Majiayao culture, during the final period of the Chinese Neolithic and beginning of the Bronze Age. In particular, it is found frequently starting with the Banshan Phase of the Majiayao (~2700-2350 BC).

It's unclear exactly how widespread the swastika was within China between the early Bronze Age and beginning of the historic period. The swastika occurs frequently in rock art dating to the late Bronze Age and Iron Age in Tibet (beginning around 1000-700 BC[1]) and into the Zhangzhung Kingdom. A swastika-like comet is recorded in a manuscript dating to ~200 BC in the Hunan Province, marking the symbol's reappearance outside of the Himalayas.

With the popularization of Buddhism, the swastika likely became an established symbol throughout China, if it was not already. Buddhism first arrived in China by the 1st century AD. From the 300s-700s AD Buddhism began a strong rise in popularity, and notable converts included Emperor Yao Xing (who reigned from 391-416 AD) and Empress Wu Zetian (who reigned 690-705 AD). During this period, it is likely that the swastika began appearing on certain Chinese coins.

It is said that Empress Wu Zetian named the swastika wàn.[2] This is the same pronunciation as 万, meaning "ten thousand" and "infinity",[2][3] indicating the swastika was viewed as an auspicious object. Empress Wu Zetian also decreed the swastika as a symbol of the sun.[4]

In Tibet, the Bon religion uses the swastika as a sacred symbol. This dates back at least to the 10th-11th centuries AD when Yungdrung Bon formed. However, the swastika was used in various religious contexts in the Tibetan Iron Age, many of which continued into Yungdrung Bon, indicating it was likely an important symbol in pre-Yungdrung Bon forms of Bon.[1]

By the 700s AD, Nestorian Christians had arrived in China, and may have used the swastika as well. There are numerous Nestorian artifacts dating to the Yuan dynasty era (1200s-1300s AD) with swastikas. This could have been a syncretic incorporation of the Buddhist swastika cross, or could indicate eastern Christians also used the swastika as a variant of the Christian cross, just as those in Europe, Egypt, and Ethiopia had done from the beginning of Christianity into the Middle Ages.

The swastika is also used in other religions in China, such as Guiyidao, a branch of the Xiantiandao religion; Shanrendao, a Confucian-Taoist religion; and Falun Gong. Adherents of Guiyidao founded the Red Swastika Society, a charitable foundation, in the 1920s, as a swastika-based counterpart to the Red Cross Society.

In the 1930s, National Socialist Germany conducted an ethnological expedition to Tibet, in order to study the religions and cultures there which had used the swastika for thousands of years. A major goal was to study the possible origins of the "Aryan race", or at the very least, better understand the history and spread of the swastika.

Throughout Chinese history, the swastika has been incorporated into various designs, such as the 万字不到头 (wànzì bù dàotóu) fret pattern, stylized shòu characters, rank badges (mandarin squares) used by Qing dynasty officials, and various other examples.

Time and time again, we find right-facing, left-facing, and rotated swastikas.

Majiayao culture

The Majiayao culture was an early farming culture in the upper Yellow River basin during the end of the Neolithic era and early Bronze Age. They were the first culture in China known to use the swastika, and it became a common motif on pottery during the Banshan phase, dating to ~2700-2350 BC.[5]

Majiayao culture (Machang Phase) ceramic shown as Figure 4.11 6. M645: 19 in Hung (2011),[5] page 321. Description: "Figure 4.11. Early MCP painted pottery vessels unearthed from Liuwan in Ledu County, Qinghai." In the Gansu-Qinghai region, the Machang Phase (MCP) of the Majiayao culture is dated to 4300-4000 BP (~2350-2050 BC.)[5]

Description: "Majiayao culture, Machang type ceramic (Gansu or Qinghai province)." The date is given as the late 3rd millennium BC (~2300-2000 BC). Item No. 0002 in the collection of The Daghlian Collection of Chinese Art, City University of New York (CUNY), USA.

https://daghlian.qc.cuny.edu/portfolio-item/jar-with-swastika-design/

Description: "Majiayao Culture: Machang type (c.2200-2000 BC), Neolithic Period." Catalog number C1979.0220 in the collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Art, China.

https://hkmasvr.lcsd.gov.hk/hkmacs_data/web/object_web.nsf/home?openform&lang=en

Photo by Flickr user brownpau.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/44124483743@N01/4966891828

For a more detailed collection of every Majiayao culture swastika I have come across, please see the following article on the world's oldest swastikas:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/worlds-oldest-swastikas.html#Majiayao

A number of other ancient cultures in China have been claimed to use the swastika, but I have found no evidence.

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/worlds-oldest-swastikas.html#OtherAncientChinese

Representation of a comet

The manuscript entitled Divination by Astrological and Meteorological Phenomena (天文氣象雜占; Tiān Wén Qì Xiàng Zá Zhàn) was discovered in Tomb Number 3 of the Mawangdui tombs from the Western Han dynasty, located in Changsha, Hunan Province, China. According to the Hunan Provincial Museum, where the manuscript is kept, it may date prior to the fall of the Chu State in 223 BC.[6] There are 250 drawings of astronomical and meteorological phenomena, including 29 drawings of comets.[6] One of the comets was recorded to have a swastika-like shape.

Detail of the Divination by Astrological and Meteorological Phenomena manuscript, showing swastika-like comet. Illustration from a republication by the Wenwu Chubanshe (Cultural Relics Publishing House).[7][8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mawangdui_Astrology_Comets_Ms.JPG

Due to the drawing showing hard right angles and symmetry, we may assume the illustrator exaggerated the shape of the comet to intentionally make it appear like a swastika. (Unless there is an astronomical reason why a comet could produce four perfect right angles with four-fold symmetry). This suggests the swastika may have been a known symbol with specific connotations during the time the manuscript was written.

In the book Comet (1985), page 181-187, Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan discuss the possibility of a comet influencing world-wide use of the swastika, and briefly discuss the manuscript.[9] Even so, in an illustration they acknowledge a swastika-like comet would produce curved "arms" from rotation, rather than the sharp 90 degree angles with which the swastika is most commonly portrayed—including in the Chinese illustration.

"Under these circumstances it is arresting to find, in the culture with the longest tradition of careful observations of comets, a straightforward, apparently unambiguous description of a swastika as just another comet. Such is the case of the twenty-ninth and final comet to appear in the ancient silk atlas of cometary forms that was unearthed in a Han Dynasty tomb at Mawangdui, China (Chapter 2). It dates from the third or fourth century B.C., but is an anthology of observations that must be much older. The twenty-ninth comet is called "Di-Xing," "the long-tailed pheasant star." The caption is the lengthiest of all twenty-nine, because the swastika comet alone is subject to differing interpretations. This comet is associated with change. "Appearing in spring means good harvest, summer means drought, in autumn means flood, in winter means small battles." Of course, these auspices are fanciful, but the origin of the swastika in a cometary apparition now seems to us a real possibility. We wonder if the connection is drawn in other little-noticed artifacts of ancient cultures."

The authors also speculate on the date range when the comets may have first been recorded:[10]

"How long would it take to assemble a catalogue of 29 distinct cometary forms? With 338 separate sightings recorded over 3,000 years in the surviving Chinese annals, the average discovery rate is about one bright naked-eye comet a decade—not too far from current values. If each of the 29 forms appears equally often, you would have to wait 29x10=290 years to see them all. But some cometary forms are much rarer than others. Thus, if every form depicted corresponds to a different comet, the Mawangdui atlas must have drawn on an earlier continuous tradition of systematic observation which precedes it by many centuries, possibly millennia. Accordingly, this splendid tradition of recording cometary forms must date back to 1500 B.C. or earlier. The earliest written and earliest graphic representations of comets thus trace back to, or at least through, the same epoch. Perhaps there was an out-of-the-ordinary comet then that commanded their attention."

The appearance of a swastika-like comet could have repopularized the symbol in the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age, but the swastika had gradually been spreading throughout the Old World since at least 6000 BC.[11] It may be of interest to note that the swastika has been found alongside symbols of the sun and moon in Iron Age Tibet, however, it may just as well be a figurative symbol rather than a literal celestial object.[1]

As a Buddhist symbol

Buddhism arrived in China by the 1st century AD,[12] likely bringing the swastika with it.

Around 400 AD, the Buddhist monk Kumārajīva had converted Emperor Yao Xing, firmly establishing Buddhism's presence in China.

Both left-facing and right-facing swastikas have historically been associated with associated with Buddhism.

***

In the 1890s, American museum curator Thomas Wilson received information about the swastika's use in Chinese history from the Chinese legation to the US.[13] Below are the examples which can reasonably be linked back to Buddhism.

For images, see our page with an abridged republication of Wilson's work:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/thomas-wilson-swastika-earliest-known.html

"A Buddhist priest of the Tang Dynasty, Tao Shih by name, in a chapter of his work entitled Fa Yuen Chu Lin, on the original Buddha, describes him as having this 卍 mark on his breast and sitting on a high lily of innumerable petals."

Empress Wu Zetian (who reigned 690-705) was also a Buddhist. It is said that she decreed that swastika should be used as a sun symbol.

"Empress Wu (684-704 A.D.), of the Tang Dynasty, invented a number of new forms for characters already in existence, amongst which [left-facing swastika in a circle] was the word for sun, [Z in a circle] for moon, [circle] for star, and so on. These characters were once very extensively used in ornamental writing, and even now the word [left-facing swastika in a circle] sun may be found in many of the famous stone inscriptions of that age, which have been preserved to us up to the present day. [Pl. 2.]"

It is said that she named the swastika wàn.[2] This is the same pronunciation as 万, meaning "ten thousand" and "infinity".[2][3][13]

Buddhist convert Emperor Daizong of Tang issued a decree forbidding the use of the swastika on fabrics. This perhaps indicates the swastika was used as a common ornament by this time, but Emperor Daizong wanted to restrict mundane uses of the sacred symbol.

"The history of the Tang Dynasty (620-906 A. D.), by Lui Hsu and others of the Tsin Dynasty, records a decree issued by Emperor Tai Tsung (763-779 A. D.) forbidding the use of the Swastika on silk fabrics manufactured for any purpose."

The Southern Tang dynasty lasted from 937-976 AD, and its emperors appear to have been Buddhist.

"The Ts’ing-I-Luh, by Tao Kuh, of the Sung Dynasty, records that an Empress in the time of the South Tang Dynasty had an incense burner the external decoration of which had the Swastika design on it."

***

The Mogao Caves are an important historic Buddhist site, which have been used as a religious site since the 300s AD. By 1000 AD, some of the caves had been sealed to protect various holy texts and valuable objects from being looted or destroyed in a period of warfare. These caves were rediscovered in 1900.

Textile with rotated left-facing and right-facing swastikas. From Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes, near Dunhuang, Gansu Province, China. 800s-900s AD. In the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, accession number LOAN:STEIN.224.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O89671/the-stein-collection-fragments-unknown/the-stein-collection-textile-unknown/

***

Reclining Buddha statue in Dafo Temple, Zhangye, Gansu Province, China. Right-facing swastika on the statue's chest. Constructed c. 1000-1200 AD. Photo by Wikipedia user Zhangzhugang, 2014.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Zhangye_Dafo_Si_2014.01.02_15-33-30.jpg

Another photo of the Reclining Buddha:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zhangyedafosi.jpg

Statues of three Buddhas in Donglin Temple, near Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province, China. Right-facing swastikas on their chests. Photo by Wikipedia user Gisling, 2010.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Donglin_Temple_Three_Buddhas.jpg

Rotated right-facing and left-facing swastikas in the window lattice at Tiantong Temple, Taibai Mountain, Zhejiang Province, China. Photo by Ernst Boerschmann, c. 1906, published on page 269 of Picturesque China; Architecture and Landscape; A Journey Through Twelve Provinces (c. 1929). The photo above has been digitally retouched by Flickr user ralphrepo_photolog, 2009.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphrepo_photolog/4167000387/in/photostream/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Der_Abt_Des_Klosters,_T%C3%ADen_t%C3%BAng_sze,_Chekiang_Province_(c1906)_Ernst_Boerschmann_(RESTORED)_(4167000387).jpg

https://archive.org/details/picturesquechina00boer/page/268/mode/2up

The Spring Temple Buddha, picturing Vairocana, in Lushan County, Henan, China. It's the 2nd largest statue in the world. Photo by Panoramio user Nyx Ning, 2013.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spring_Temple_Buddha_1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spring_Temple_Buddha

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Spring_Temple_Buddha

Logo of the Hong Kong Buddhist Association. Photo taken on Eastern Hospital Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Island, China. Photo by Wikipedia user BEVERLYSHEN, 2006.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HK_Eastern_Hospital_Road_11_HK_Buddhist_Association_Cultural_Ctr.jpg

Description: "a Hong Kong Buddhist School". Photo by Wikipedia user Deutsch Fetisch, 2008.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Buddhist_School_Hong_Kong.jpg

Rotated, right-facing swastika. Description: "Buddhist swastika on a doorway in Wuren, China". Uploaded to Reddit by user 127-0-0-1_1, July 8, 2017. I was unable to find information about a place called "Wuren" in China.

https://old.reddit.com/r/mildlyinteresting/comments/6lzztk/i_found_an_actual_buddhist_swastika_on_a_doorway/

***

If you want to dive in and try to catalog every potential Buddhist swastika in China, you can start here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Buddhist_temples_in_the_People%27s_Republic_of_China

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Buddhist_architecture_in_China

The swastika as a Nestorian Christian symbol

The Church of the East in China, or Nestorian Church, was part of a major branch of Eastern Christianity. In the 600s AD the church became established in China,[14] but it declined after 845 when Christianity was banned by Emperor Wuzong.[15] The Mongolian Yuan dynasty of China allowed the church to return in the 1200s, but it again declined by the rise of the Ming dynasty in the mid-1300s.[14]

Like early and Medieval Christians in Europe, Egypt, and Ethiopia, Nestorian Christians used the swastika as a variant of the cross. Alternatively, their use of the swastika may have been influenced by the popularity of Buddhism in the Yuan dynasty.

The University Museum and Art Gallery of The University of Hong Kong has a collection of Nestorian bronze ornaments which they attribute to the Yuan dynasty. The swastika is one of the most common symbols. The website lists the Collection Number HKU.B.1961.0243, but not the specific numbers of each of the dozen of artifacts photographed.

https://umag.hku.hk/collection/nestorian-crosses/

Below are all the artifacts with swastikas. There are some repeats in the photos.

Original source unspecified. A similarly-labeled photo is of an artifact from The University Museum and Art Gallery of The University of Hong Kong, and this artifact appears to be one of the artifacts in the first image of this section.

https://preview.redd.it/b91fjybz60021.jpg

***

Many other examples of Nestorian artifacts with swastikas can be found in other museum collections, auctions, and websites.

Nestorian Cross, Yuan dynasty, late 13th century to early 14th century AD. In the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Accession Number 1972-111-17.

https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/67499

Collection of Nestorian Bronze Crosses, Yuan dynasty. Auctioned on the website iGavel Auctions, by user LarkMasonAssoc, April 30, 2014, New York, New York. Lot Number and ItemID 3389531.

https://bid.igavelauctions.com/Bidding.taf?_function=detail&Auction_uid1=3389531

Nestorian Cross, Yuan dynasty, 13th - 14th century AD. In the collection of The Museum of East Asian Art, Bath, UK. Record number BATEA : 279.

http://collections.meaa.org.uk/

Stamp seal with swastika. The museum labels the artifacts as "Ordos region 3rd/2nd millenium", but compare with the Nestorian designs. In the collection of The Museum of East Asian Art, Bath, UK. Record number BATEA : 1286.

http://collections.meaa.org.uk/

Bronze with swastika-like motif. In the collection of The Museum of East Asian Art, Bath, UK. Record number BATEA : 1189.

http://collections.meaa.org.uk/

Nestorian Crosses from the 12th-14th centuries AD. Exhibited in the Royal Ontario Museum, although I do not see the one with a swastika in their online collections. Photo by Flickr user mavra_chang, 2008.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/mavra_chang/2241297740/in/photostream/

Figure showing a Nestorian Cross, reposted on the website SlideShare.[16] Original source unknown.

https://image.slideserve.com/411454/nestorian-christianity-l.jpg

As a symbol in other religions

Guiyidao is a religion belonging to the Xiantiandao faith, founded in 1916. Xiantiandao can be traced back to the 1200s-1300s AD during the Yuan dynasty. (See also Xiantiandao's use of the swastika in Taiwan.)

A symbol of Guiyidao.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Guiyidaoyuan.svg

In 1922, the religion founded the Red Swastika Society, which has a mission of philanthropic and charitable acts.[17][18]

A member of the Red Swastika Society.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Red_Swastika_Society_member.jpg

Alcove in front of the Red Swastika Society building at 25 Dragon Road in Hong Kong, China. Photo by Wikipedia user Yauhangyats, 2012.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HK_Tin_Hau_%E9%87%91%E9%BE%8D%E9%81%93_25_Dragon_Road_%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF%E7%B4%85%E5%8D%8D%E5%AD%97%E6%9C%83_Hong_Kong_Red_Swastika_Society_July-2012.jpg

The website "Medals of Asia"[18] has dozens of examples of Red Swastika Society badges and photos.

"The Red Swastika Society/世界紅卍字會 was a voluntary association founded in China in 1922 by Qian Nengxun/錢能訓, Du Bingyin/杜秉寅 and Li Jiabai/李佳白. Together with the organisation's president Li JianChiu/李建秋, they set up their establishment of the federation in Beijing as the philanthropic branch of the Chinese salvationist religion Guiyidao/皈依道, the "Way of the Return to the One". Association ran poorhouses and soup kitchens, as well as modern hospitals and other relief works. It had an explicit internationalist focus, extending relief efforts to Tokyo after earthquakes and also in response to natural disasters in the Soviet Union. In addition, it had offices in Paris, London, and Tokyo and professors of Esperanto within its membership .Reports of its strength during the 1920s and 1930s seem to vary widely, with citations of 30 000 "members" in 1927 to 7–10 million "followers" in 1937."[18]

Red Swastika Society medallion, from the Taiyuan branch, Shanxi Province, China. Image and translation posted on the website Medals of Asia.[18]

Red Swastika Society badge, from the Changzhou branch, Jiangsu Province, China. Image and translation posted on the website Medals of Asia.[18]

Medical staff at the Shanghai Red Swastika Hospital, during the 1937 Battle of Shanghai. Photo by Malcolm Rosholt; image reuploaded on the website Medals of Asia.[18]

***

Shanrendao is a Confucian-Taoist religion centered in northeastern China. It uses swastikas in its iconography.

A swastika used by Shanrendao.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wanguo_Daodehui.svg

Another swastika used by Shanrendao.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shanrendao.svg

***

Falun Gong is considered a cult with far-right political leanings, or spiritual cultivation method, depending on who you ask.

Its emblem features several swastikas.

Falun Gong emblem.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Falun_Gong_Logo.svg

Chinese coins

It is difficult to estimate an exact date for when the swastika appeared on ancient Chinese coins. I found examples of swastikas on the wu zhu coins, which were minted from 118 BC to 621 AD. Presumably the swastika was not used on coins until Buddhism became popular in China, around 400 AD.

"Auspicious symbols such as the swastika can also be found on wu zhu coins.

As mentioned, many of these coins with "numbers", characters and symbols were cast beginning in the Eastern Han Dynasty and continued until production of the wu zhu coin finally ceased near the end of the sixth century. This was a period of tremendous unrest and economic insecurity where official government coins as well as local and privately cast coins existed.

[...]

The wu zhu or wu shu (五 铢) coin was first cast in the fifth year (118 BC) of the Yuan Shou reign of Emperor Wu of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC - 24 AD).

[...]

The "five zhu" or wu zhu coin replaced the ban liang coin. Huge quantities of wu zhu coins were produced during the Western Han Dynasty alone and wu zhu coins continued to be cast throughout the dynasties that followed until they were finally replaced by the kai yuan tong bao coin in 621 AD at the beginning of the Tang Dynasty. The wu zhu was used for over 700 years making it the longest used coin in Chinese history.

[...]

As already stated, beginning with the Eastern Han Dynasty and continuing until the Tang Dynasty, it is very difficult to identify where and when many wu zhu coins were cast. This is because coins at this time were cast in bronze molds and, since these molds would last a long time, they continued to be used over and over again by subsequent dynasties."[19]

***

"Some of the lead coins from this period cannot as yet be attributed to a specific kingdom and ruler.

This is an example of such a lead coin that can only be attributed to the Southern Han Kingdom or Kingdom of Chu and which was most likely cast in the period 900-971.

The inscription reads wu zhu (五 铢) and the coin resembles the wu zhu coins of the Han and later dynasties.

The coin is distinctive because of the swastikas above and below the square hole.

The swastika, which can also be found on earlier wu zhu coins, is an ancient Chinese symbol and is believed to represent the Chinese character wan (万) meaning "ten-thousand". The extended meaning is "many".

The swastika is also an ancient Buddhist symbol and Buddhism was a major religion in China at the time this coin was cast."[20]

Chinese wu zhu lead coin with swastika, described above on the website "Primal Trek".[20] Southern Han Kingdom or Kingdom of Chu, c. 900-971 AD.

***

"Liu Hai (刘海) is one of the most popular members of the Chinese pantheon of charm figures and represents prosperity and wealth. There are a couple of versions of the story which have come down through history.

Liu Hai and three legged toad charm

Liu Hai was a Minister of State during the 10th century in China. He was also a Taoist practitioner. One version of the story says that he became good friends with a three-legged toad who had the fabulous ability to whisk its owner to any destination. This particular toad had a love not only for water but also for gold. If the toad happened to escape down a well, Liu Hai could make him come out by means of a line baited with gold coins.

The second version of the story is that the toad actually lived in a deep pool and exuded a poisonous vapor which harmed the people. Liu Hai is said to have hooked this ugly and venous creature with gold coins and then destroyed it.

[...]

The inscription surrounding the circular hole reads jin yu man tang, chang ming fu gui (金玉满堂长命富贵) which translates as "may gold and jade fill your halls" and "longevity, wealth and honor".

The reverse side of this charm, shown here, displays Eight Treasures. Starting at the one o'clock position and moving clockwise are the swastika (meaning 10,000), rhinoceros horn, writing brush with silver ingot, coral, lozenge, yinyang mirror, ruyi sceptre, and pearl."[21]

Chinese Liu Hai charm coin with swastika, described above on the website "Primal Trek".[21]

Chinese numismatic charms originated around 2000 years ago in the Western Han dynasty, and are said to have remained common into the republic period in China.

Geometric fret design with connected swastikas

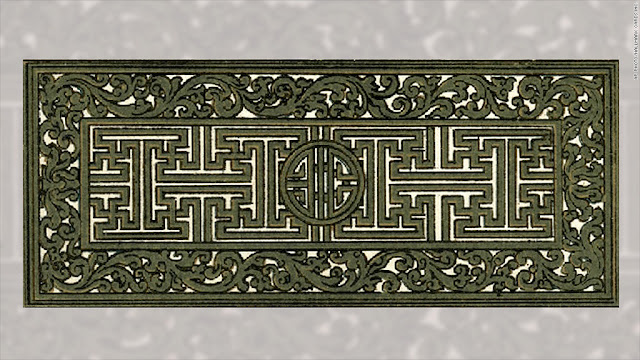

In Chinese design, there is a geometric pattern composed of swastikas called 万字不到头 (wànzì bù dàotóu). It is a geometric fret comprised of connected swastikas. It can be found as a lattice on railings and fences, windows, and furniture; as a carving in wood; and a two-dimensional design in paintings and fabric patterns.

This pattern presumably originates in China and later spread to Korea, Japan, Mongolia, and probably elsewhere. In Japanese it's called 紗綾形 / さやがた (sayagata), in Mongolian it's called түмэн наст (tumen nast), and I have not yet found what it's called in Korean.

An internet search for "万字不到头" shows that there are multiple different patterns that can fall under this name. The one below appears to be the most common configuration in Chinese and other cultures.

Geometric swastikas in 万字不到头 (wànzì bù dàotóu) pattern. Photo by Wikipedia user 用心阁, 2005.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wanzibudaotou_1.JPG

Geometric swastikas in 万字不到头 (wànzì bù dàotóu) pattern on curtains. Beijing, China. Photo by Wikipedia user N509FZ, 2014.

https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh/File:Sayagata_curtains.JPG

Geometric swastikas in 万字不到头 (wànzì bù dàotóu) pattern on a wall. Photo by Wikipedia user Yongxinge, 2006.

https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh/File:Sayagata_motives_on_wall.jpg

Description: "Sutra Cover with Multicolored Clouds on an Overall Fretwork", Ming dynasty, 1500s AD. In the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Accession Number 2011.221.32.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/76623

See also the Wikipedia entry:

https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%87%E5%AD%97%E4%B8%8D%E5%88%B0%E5%A4%B4

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%87%E5%AD%97%E4%B8%8D%E5%88%B0%E5%A4%B4

This pattern is also visible on the picture frame of the portrait of Empress Dowager Cixi, shown in the following section. Additionally, it is visible on the Alexander and Baldwin Building in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA.

A holiday wrapping paper with this design was banned in certain US stores in 2014 due to ignorance. See the section on prejudice against the swastika.

Shou character

A few other examples of Chinese swastikas from 600 AD onward can be seen in Wilson (1898).[13]

I will draw particular attention to one example:

"Mr. Chung, dressed in his robes of state; his outer garment was of moiré silk. The pattern woven in the fabric consisted of a large circle with certain marks therein, prominent among which were two Swastikas, one turned to the right, the other to the left. The name given to the sign was reported above, wan, and the significance was "longevity," "long life," "many years.""

Mr. Chung may have been wearing a shòu (壽) character, which means longevity and is frequently stylized and used in Chinese motifs. Swastikas can be used to amplify the meaning of the character. A few examples of shòu motifs with two swastikas can be seen below.

Portrait of Empress Dowager Cixi, by Katherine A. Carl, 1903. The Empress is has shòu motifs with swastikas on her clothing. The picture frame also has swastikas.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Empress_Dowager_Cixi_by_Katherine_A._Carl,_view_2,

_China,_1903_AD,_oil_on_canvas,_camphor_wood_frame_-_Peabody_Essex_Museum_-_DSC08060.jpg

_Walters_491685_Profile.jpg)

Description: "Flask with the "Eight Auspicious Symbols" (bajixiang)". Qing dynasty, c. 1736-1795 AD. In the collection of The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Accession Number 49.1685.

https://art.thewalters.org/detail/30829/pilgrim-bottle-with-the-character-shou-long-life/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chinese_-_Pilgrim_Bottle_with_the_Character_%22Shou%22_(Long_Life)_-_Walters_491685_-_Profile.jpg

Ornamentation on the Great Wall, near Beijing. Photo by Wikipedia user David Block (pitti), 2005.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stone_Figures_Great_Wall.JPG

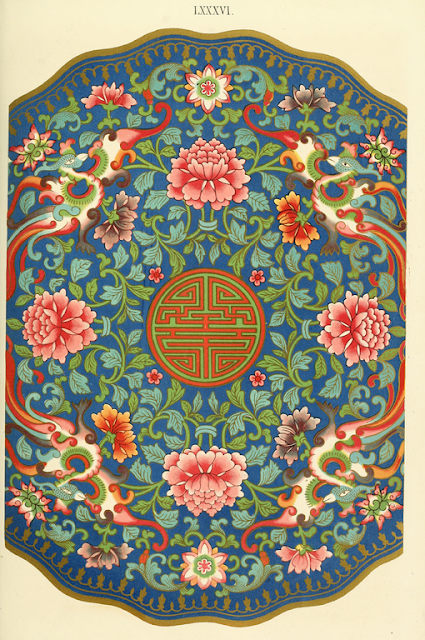

Plate LXXXVI in Jones (1867),[22] showing shou character with two swastikas. Also see Plate LXXXII for an example of a swastika fret and LII for a single swastika (without being incorporated into a shou character).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Owen_Jones_-_Examples_of_Chinese_Ornament_-_1867_-_plate_086.png

Jones does not specify exactly which collection this example is from, but he almost gleefully recounts how the art in his book was looted:

"The late war in China, and the Ti-ping rebellion, by the destruction and sacking of many public buildings, has caused the introduction to Europe of a great number of truly magnificent works of Ornamental Art, of a character which had been rarely seen before that period, and which are remarkable, not only for the perfection and skill shown in the technical processes, but also for the beauty and harmony of the colouring, and general perfection of the ornamentation.

I have had the advantage of access to the National Collection at South Kensington and the unrivalled collection of Alfred Morrision, Esq., of Fonthill, who has secured the finest specimens from time to time, as they have appeared in this country. From the collection of Louis Huth, Esq., exhibited in South Kensington, and from many objects in the possession of M. Digby Wyatt, Esq., Col. De La Rue, Thomas Chappell, Esq., F. O. Ward, Esq., Messrs. Nixon and Rhodes, and others, the bulk of the compositions have been obtained. My thanks are especially due to Messrs. Durlacher and Mr. Wareham for the liberal loan of many objects, which I have been thus enabled to copy in the quiet of the studio."

An example of swastikas near a shòu character without being integrated into it. Textile from the 1600s in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession Number 46.133.11.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/60930

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MET_DP225675.jpg

See also the shòu characters used on the Alexander and Baldwin Building in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA:

https://aryan-anthropology.blogspot.com/p/swastikas-in-oceania-melanesia.html#ChineseCultureInHawaii

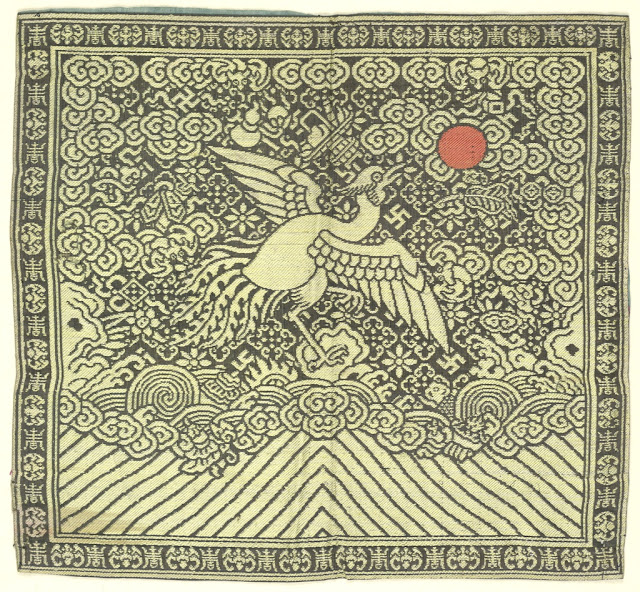

Chinese rank badges (mandarin squares)

Rank badges or mandarin squares were patches sewn onto the garments of imperial officials in China, indicating their rank. Many of these badges had swastikas and other auspicious symbolism.

Rank badge with heron and auspicious symbols. Qing dynasty, 1800s AD. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1959-64-2, Object ID 18426389.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18426389

Below are the examples of rank badges in the Cooper Hewitt museum which have swastikas.

Rank badge with peacock and rotated swastika near its left wing. Qing dynasty, mid-1800s AD. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1941-31-44, Object ID 18563209. Another photo is given Accession Number 1941-31-45-a,b, Object ID 18563211.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18563209/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18563211/

Rank badge with bird in the center and a right-facing swastika to its left and a rotated left-facing swastika to its right. Alternating right-facing and left-facing swastikas form the border of the square. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1943-31-11, Object ID 18568957.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18568957/

Rank badge with bird in the center and alternating right-facing and left-facing swastikas forming the border of the square. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1971-50-528, Object ID 18474917.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18474917/

Rank badge with bird in the center and alternating right-facing and left-facing swastikas forming the border of the square. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1960-233-1, Object ID 18665581.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18665581/

Rank badge with bird in the center and alternating right-facing and left-facing swastikas forming the border of the square. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1960-233-2, Object ID 18432773.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18432773/

Rank badge with bird in center and rotated left-facing swastika below its left wing. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1959-64-1, Object ID 18426387.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18426387/

Rank badge with bird in center and numerous rotated right-facing swastikas in the background, with a single rotated left-facing swastika above the left wing. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1976-116-5-a, Object ID 18490401. Another photo is given Accession Number 1976-116-5-b,c, Object ID 18490403.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18490401/

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18490403/

Rank badge with bird in center and numerous rotated right-facing swastikas in the background. Qing dynasty, 1800s AD. In the collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York. Accession Number 1976-116-4-a,b, Object ID 18490399.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18490399/

Other and general examples in China

The following are the rest of the references to Chinese swastikas from Wilson (1898).[13]

"Fung Tse, of the Tang Dynasty, records a practice among the people of Loh-yang to endeavor, on the 7th of the 7th month of each year, to obtain spiders to weave the Swastika on their web. Kung Ping-Chung, of the Sung Dynasty, says that the people of Loh-yang believe it to be good luck to find the Swastika woven by spiders over fruits or melons."

*

"Sung Pai, of the Sung Dynasty, records an offering made to the Emperor by Li Yuen-su, a high official of the Tang Dynasty, of a buffalo with a Swastika on the forehead, in return for which offering he was given a horse by the Emperor."

*

"Chu I-Tsu, in his work entitled Ming Shih Tsung, says Wu Tsung-Chih, a learned man of Sin Shui, built a residence outside of the north gate of that town, which he named “Wan-Chai,” from the Swastika decoration of the railings about the exterior of the house."

*

"An anonymous work, entitled the Tung Hsi Yang K’ao, described a fruit called shan-tsao-tse (mountain or wild date), whose leaves resemble those of the plum. The seed resembles the lichee, and the fruit, which ripens in the ninth month of the year, suggests a resemblance to the Swastika."

*

"The Swastika is one of the symbolic marks of the Chinese porcelain. Prime110[23] shows what he calls a “tablet of honor,” which represents a Swastika inclosed in a lozenge with loops at the corners (fig. 31). This mark on a piece of porcelain signifies that it is an imperial gift.

110 “Pottery and Porcelain,” p. 254."

*

"Major-General Gordon, controller of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, England, writes to Dr. Schliemann:111[24] “The Swastika is Chinese. On the breech chasing of a large gun lying outside my office, captured in the Taku fort, you will find this same sign.”

111 “Ilios,” p. 352."

*

"Mr. R. E. Martyr (letter of January 20, 1898) notifies of the occurrence of variations of the swastika occurring in Solo, a dialect of western Ssu-ch'uan, citing Baber's Travels in 1881; also a Journey in that country, by Mr. F. S. A. Bourne, Parliamentary Papers C. 5371/88, China No. 1, 1888."

(Above is referring to the Lolo (Yi) language of the Sichuan province.)

***

On the Wikipedia page for swastika, without a source it claims:[25]

"The character wan can also be stylized in the form of the xiangyun, Chinese auspicious clouds."

This may be a reference to two images posted in this article: the rank badge in the Cooper Hewitt collection (Object ID 18426389) and the fabric in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Accession Number 2011.221.32). These appear as examples on the Wikipedia page for xiangyun, even though the swastikas themselves are not being used as clouds.[26]

***

Description: "A family in Lanzhou, China, 1944." Photo by Mark Tennien. Photo in the collection of the Maryknoll Mission Archives, University of Southern California Libraries, unique identifier number UC1870610.

https://digitallibrary.usc.edu/asset-management/2A3BF1K8AM9X

Photo believed to be taken in WWII era China, at an unknown location. In the bottom-right, there is a large swastika on the roof. Description: "Found on a Chinese web site dedicated to the war years, it seems to have been taken from a private Japanese photo album." Reuploaded to Flickr by user ralphrepo_photolog, 2009.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ralphrepo_photolog/4075720736/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bomb_Protection_(c1940)_Attribution_Unk_(RESTORED)_(4075720736).jpg

***

The following are images of a Chinese medal with a swastika. A translation of the text is not provided. I wonder if it is associated with the Red Swastika Society; however, it appears that the swastikas on their medallions are actually red.

Description: "Medal of the Chinese Charities Federation, Republican era (1912-1949). Bought in flea market in Xining, China." Uploaded to Wikipedia by user Krokodyl, 2008.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:China_swastika.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Writing_detail,_China_swastika_(cropped).jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:China_swastika_(cropped).jpg

***

Grain measure box with swastika on the base. Date unknown. In the Forbidden City, Beijing, which was constructed from 1406-1420 AD and used as an imperial palace until 1924. Photo by Flickr user l-michael-roberts, 2005.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/l-michael-roberts/31344933/

Roof decorations on the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the largest hall within the Forbidden City. Photo by Wikipedia user PIERRE ANDRE LECLERCQ, 2011.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:P%C3%A9kin,_Chine,_La_Cit%C3%A9_interdite,_(3).jpg

***

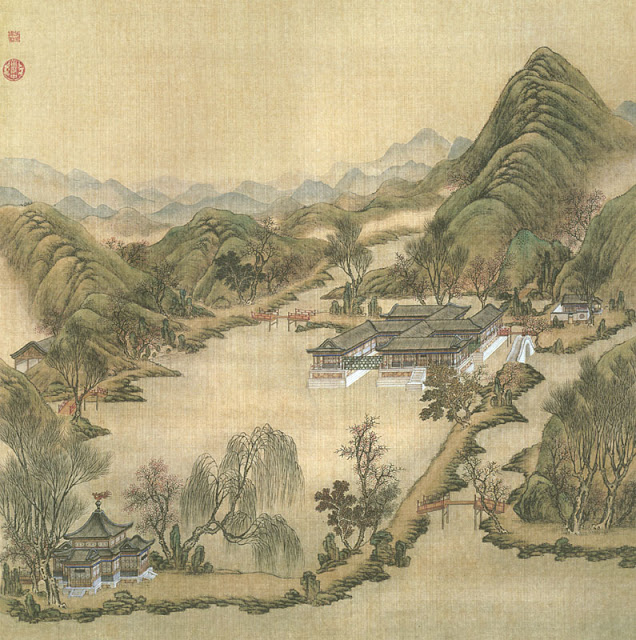

The Old Summer Palace, located in Beijing, began construction in 1707. In 1744, the Qianlong Emperor commissioned a series of paintings titled Forty Scenes of the Yuanmingyuan, which show different views of the palace complex.

Painting 13 is entitled "Universal Peace Building (Swastika House)", showing a building in the shape of a swastika.

"This island was dominated by a building in the shape of a Chinese character meaning Buddha’s heart 卍. It is pronounced wan, and is a homophone with another wan meaning ten thousand, or everywhere. Western observers in later times termed it the Swastika House. Built on a stone and brick foundation and surrounded by water and backed by a hill, this complex was “cool in the summer and warm in the winter.” This was a favorite spot for evening strolls and watching the moon.""[27]

The Universal Peace Building at the Old Summer Palace, Beijing. (Zoom in for details).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Universal_Peace_Building.jpg

During the Second Opium War, French and British troops captured the palace on 6 October 1860, looting and destroying the imperial collections over the next few days.[4][5] As news emerged that an Anglo-French delegation had been imprisoned and tortured by the Qing government, with 19 delegation members being killed,[6] the British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, retaliated by ordering the complete destruction of the palace on 18 October, which was then carried out by troops under his command.[5] The palace was so large – covering more than 3.5 square kilometres (860 acres) – that it took 4,000 men three days to destroy it.[7] Many exquisite artworks – sculptures, porcelain, jade, silk robes, elaborate textiles, gold objects and more – were looted and are now located in 47 museums around the world, according to UNESCO.[8]"[28]

(James Bruce's father had "acquired" the famous "Elgin Marbles" from the Parthenon in Greece. I guess it ran in his blood.)

***

Description: "Mirror Case with Filled Diagonal Lattice and Swastikas (Wan)". Qing dynasty. In the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession Number 30.75.790.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54413

Swastikas on a wood panel. Qing dynasty. In the collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Object number 94-10-2.16.

https://www.penn.museum/collections/object/168527

Farming in style. Description: "A YY-200 tractor with trailer in a village near Dali, Yunnan." Photo by Wikipedia user BrokenSphere, 2008.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Red_YY-200_tractor_with_trailer.JPG

***

Chapter 12 of the book On the Ancient History of the Silk Road (2021)[29] discusses the swastika in China, but I've been unable to find an available copy of this book.

Swastikas in Taiwan

As a Buddhist symbol

A Buddhist prayer room in the Taoyuan International Airport, Taoyuan, Taiwan, is marked with a swastika. Photo by Flickr user wongwt, 2014.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/wongwt/13778671553/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prayer_Room_(13778671553).jpg

Taipei subway map showing temples marked with swastikas. Yongan Market Taipei Mass Rapid Transit Station. Photo by Wikipedia user Allen Timothy Chang, 2005.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taipei_subway_temple_symbol.jpg

Swastika in a Buddhist temple in Taitung, Taiwan. Photo by Flickr user gusthead, 2005.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/gusthead/5772251642/

***

If you want to dive in and try to catalog every potential Buddhist swastika in Taiwan, you can start here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Buddhist_temples_in_Taiwan

As a Xiantiandao symbol

See also the section about the swastika in Xiantiandao in mainland China.

Swastikas on a wall of the Chengyuan Tang Temple, Chang'an Village, Magong, Penghu County, Taiwan. Photo by Wikipedia user 舟集 Toadboat, 2020.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2020_%E6%BE%84%E6%BA%90%E5%A0%82_(1).jpg

Other photos of the temple can be seen at the following link:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Chengyuan_Tang_Temple

Other and general examples in Taiwan

Bus shelter in Xiangtianhu, Taiwan. Photo taken by Wikipedia user Kai3952, 2020.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Front_left_view_of_Xiangtianhu_bus_shelter,_as_taken_on_9th_October_2020.jpg

Other photos:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Xiangtianhu_bus_shelter

Swastikas in Tibet

Rock art in the Zhangzhung Kingdom and elsewhere in ancient Tibet

John Vincent Bellezza, an archaeologist specializing in ancient Tibetan history, has written a number of articles about swastikas in Tibetan petroglyphs from the late Bronze age, early Iron Age, and into the historic period.[1][30][31] Below are a few of the swastikas from his articles. In two online articles, he published 84 photos of swastikas used on Tibetan rock art spanning over thousands of years.[30][31] In total, he's documented over 300 ancient Tibetan swastikas,[30][1] primarily from the western regions of Changthang and Ladka.

This style of rock art first appears around 1000-700 BC, and is associated with the emergence of the Zhangzhung kingdom in the western Tibetan Plateau.[1] Zhangzhung had collapsed and was annexed into the Tibetan Empire in the 600s AD.

Left-facing, right-facing, and rotated swastikas can be seen.

After the Majiayao culture swastikas, these late Bronze Age and early Iron Age swastikas in Tibet are the oldest known swastikas in "East Asia".

***

"Over the course of the last two decades, I have documented close to 300 swastikas in Upper Tibet carved and painted on boulders, cliffs, ancient ruins, and in caves. This curious sign occurs at approximately 70% of the more than seventy rock art sites discovered in the region.

[...]

The Tibetan word for swastika, yungdrung (g.yung drung) is not derived from the Sanskrit (nor are words for the swastika in Mongolian, Chinese, Albanian, etc.). This term has a Bodic linguistic lineage. Among the earliest recorded uses of yungdrung occur in manuscripts and pillar inscriptions of Tibet’s Imperial period (circa 650–850 CE). There are several examples of the word yungdrung appearing in the pillar edicts and chronicles of the Tibetan kings, where it signifies stability and eternity.

[...]

In the extinct Zhang Zhung language of western Tibet, the word for swastika is drung mu, which is etymologically related to its Tibetan equivalent.

[...]

Thus far, the oldest archaeological evidence for the swastika in Tibet appears in the rock art record of the western third of the Plateau. My research shows that the swastika arose there as a sacred symbol no later than the Iron Age, laying the foundation for it becoming one of the most loved and popular symbols in the Tibetan world.

[...]

Rock art featuring the swastika, sun and moon can be dated to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE).* The wide geographic and chronological range of this distinctive ensemble of celestial symbols suggests that it played an essential mythological/religious role in ancient Upper Tibet.

* Dates provided for rock art are estimates based on various criteria. On the dating of rock art in Upper Tibet and other western regions of the Tibetan Plateau, see various earlier works by the author, such as the August 2015 Flight of the Khyung."[30]

"Rock art swastikas in Upper Tibet face in both directions and range in execution from crudely scrawled to adeptly drawn. Relying on inductive means of chronological analysis, it appears that early examples date to the Late Bronze Age (1000–700 BCE) and Iron Age (ca. 700–100 BCE), and continued to be made in the Protohistoric period (ca. 100 BCE to 650 CE), Early Historic period (ca. 650–1000 CE) and Vestigial period (ca. 1000–1300 CE).5 Thus, painted and carved swastikas span a wide spectrum of time, ranging from the initial stages of Tibetan civilization to the time of the empire and finally to the termination of the great rock art tradition in Tibet in the early centuries of the second millennium CE.

I have documented close to 300 swastikas in Upper Tibetan rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs), making it the most common sign or symbol (an abstraction encapsulating philosophical, ritualistic mythic, or mystical forms of understanding). [...] Swastikas in the rock art of Upper Tibet, depending on the pictorial context, appear to have had diverse functions comprised of cosmological, fertility, apotropaic, benedictory, doctrinal, and sectarian elements.

[...]

In prehistoric rock art, swastikas were oriented indiscriminately in both directions and often with arms out of sync.

[...]

5. Due to a lack of archaeological indicators, no attempt has been made to differentiate the Late Bronze Age from the Early Iron Age. I have devised a relative chronology for Upper Tibetan rock art based on various strands of evidence, including cultural and historical analysis, stylistic and thematic categorization, general site characteristics, associative archaeological data, gauging environmental changes in subject matter, examination of techniques of production, placement of superimpositions, and assessment of erosion and re-patination of petroglyphs and browning and ablation of pictographs. Dates determined using this inductive approach are provisional and unverifiable, but must suffice until more objective means of chronological analysis become scientifically feasible. On dating Upper Tibetan rock art, see Bellezza 2008, pp. 162, 163; Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 6–9; Suolang Wangdui 1994, pp. 33, 34; Chayet 1994, pp. 55, 56."[1]

Swastika, sun, and moon on painted rock art. Eastern Changthang region, Tibetan Plateau. Iron Age. Photo by John Vincent Bellezza.[30]

https://www.tibetarchaeology.com/may-2016/

Swastika, sunwheel, and moon on painted rock art. Western Tibet. "Probably Iron Age." Photo by John Vincent Bellezza.[30]

https://www.tibetarchaeology.com/may-2016/

Description: "Two primitive swastikas on boulder, western Changthang. Probably Iron Age, as suggested by the general contents of the site." Photo by John Vincent Bellezza.[31]

https://www.tibetarchaeology.com/june-2016/

Description: "Fig. 36. This style of swastika is distinguished by carved parallel lines, central Changthang. Located at same site as fig. 35. Iron Age or Protohistoric period." Photo by John Vincent Bellezza.[31]

https://www.tibetarchaeology.com/june-2016/

Description: "Two swastikas, tree and sun, western Changthang. The swastika on the left has legs oriented in the same direction on each axis, interrupting the radial symmetry of this geometric form. Swastikas with legs out of sync are commonplace in the early rock art of Upper Tibet. These kinds of eccentric swastikas are still seen occasionally in contemporary Tibetan folk art. Probably Iron Age." Photo by John Vincent Bellezza.[30]

https://www.tibetarchaeology.com/may-2016/

See Bellezza's articles for more:

https://www.tibetarchaeology.com/may-2016/

https://www.tibetarchaeology.com/june-2016/

As a Bon religion symbol

The Bon religion was a major religion in part of Tibet prior to the introduction of Buddhism, and since at least the 10th and 11th centuries AD it has been considerably influenced by Buddhism.[1] It is estimated to have around 400,000 followers today.[32]

Yungdrung (g.yung drung) is a word for swastika and is considered a sacred symbol in Bon. More specifically, the form of Bon practiced today is called Yungdrung Bon. Yungdrung Bon formed in the 10th and 11th centuries AD.[1] Earlier forms of Bon most likely used the swastika as well—the symbol has been used in Tibet since at least 1000-700 BC, frequently in conjunction with religious motifs which continued to be used in Yungdrung Bon.[1]

A swastika used in Yungdrung Bon. Location and photographer unknown.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bon_-_Yungdrung.jpg

"As important as the swastika is to Buddhism, it has an even more vital role in the other major religion of Tibet: Bon. The swastika is the main epithet for that religion, which has called itself Yungdrung or the ‘Eternal’ Bon for a thousand years. According to the Bon tradition, g.yung drung means ‘unborn, undying’, and is synonymous with eternity, immutability and imperishability."[30]

"The counterclockwise swastika (g.yung drung) is the quintessential symbol of Yungdrung Bon, as well as an epithet for the religion itself. Numerous adherents, deities, sites, and temples are called swastika in Yungdrung Bon. The swastika is also a referent for many of its doctrines. For instance, religious heroes are called the ‘impeccable beings of the swastika’ (g.yung drung sems dpa’), the enlightened form is referred to as g.yung drung sku, and the path to liberation is the g.yung drung grub lam. The Yungdrung Bon expression for enduring good health and longevity is ‘swastika of life’ (tshe yi g.yung drung). The swastika is of course also a key symbol in Buddhism (oriented clockwise) and Tibetan folk religion (oriented in both directions).

[...]

The pairing of a swastika with a crescent moon strongly suggests that the former is a solar symbol. The swastika as betokening the sun is well known in numerous cultures of ancient Eurasia, and the same holds true of ancient Tibet. This is chronicled in the text Klu ’bum khra bo (probably first compiled in the 10th century CE), in a creation myth centered around a goddess named Queen of the Water Spirits (Klu’i rgyal mo).8 This pantheistic goddess fashioned the universe out of her body parts, and from the light rays of her left eye appeared the sun, called the ‘unsurpassable swastika’ (g.yung drung gyi bla na med pa).

8. For a translation and discussion of the entire myth, see Bellezza 2008, pp. 343–349."[1]

"The legacy of conception and design in Yungdrung Bon extends beyond the bounds of the extant religion to encompass earlier elements of figuration and symbolism. The oldest antecedents are seen in the rock art of Upper Tibet (Byang thang and Stod), the expansive highlands north and west of Central Tibet. This rock art is characterized by a wide array of prototypes of what would become prime Yungdrung Bon portrayals. This article focuses on five categories of these rock carvings and paintings, precursors to Yungdrung Bon subjects and emblems. The five categories include the swastika (g.yung drung) [...]"[1]

Description: "The Bonpo Deity Kunzang Akor, Central Tibet, 16th century." In the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Indian Art Special Purpose Fund (M.83.191).

https://collections.lacma.org/node/247976

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Bonpo_Deity_Kunzang_Akor_LACMA_M.83.191_(1_of_2).jpg

A boy holding a wooden chakshing. Original photo source unknown. Posted by Raven Cypress Wood in 2014.

https://web.archive.org/web/20201001055729/https://ravencypresswood.com/2014/02/21/sacred-symbols/

As a Buddhist symbol

In the 600s AD both Indian and Chinese variants of Buddhism gained influence in the Tibetan Empire under King Songtsän Gampo. According to legend, however, the earliest Buddhist teachings could have arrived in the 200s AD. Buddhism became a state religion by the late 700s AD.[31]

Although in many countries, Buddhists have tended to use left-facing swastikas, it appears that due to Bon's use of the left-facing swastika, many Buddhists in Tibet commonly use right-facing swastikas:

"In the period in which this rock art was made, [Early Historic period, c. 650-1000 AD] the orientation of swastikas took on sectarian overtones. The counterclockwise version came to be associated with bon and the clockwise variety with Buddhism, a sectarian distinction largely maintained to the present day."[1]

"As we saw in the first part of this article, Buddhists in Tibet have used the swastika as a doctrinal and mystical symbol since the Early Historic period. The Buddhist swastika, however, almost always faces in a clockwise direction. It appears therefore that the counterclockwise variety was propagated in contradistinction to Buddhism. This heralds the start of a sectarianism in Tibet graphically displayed in the orientation of swastikas. Swastikas carved and painted indiscriminately in either direction, the norm in the prehistoric epoch (although counterclockwise ones were most common), acquired directional connotations in the Early Historic period. The counterclockwise swastika as a key non-Buddhist religious symbol is extensively treated in the scriptures of Yungdrung Bon."[31]

Right-facing swastika in the shape of a cloud, painting in the Sera Monastery, Lhasa, Tibet, China. The Monastery was established in the 1400s AD. Photo by Panoramio user Hiroki Ogawa, 2014.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sera_Monastery_Lhasa_Tibet_China_%E8%A5%BF%E8%97%8F_%E6%8B%89%E8%90%A8_%E8%89%B2%E6%8B%89%E5%AF%BA_-_panoramio_(3).jpg

Tenzin Gyatso, 14th Dalai Lama of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, sitting above left-facing and right-facing swastikas. Photo exhibited at the Castello di Rivoli art museum during the "Paola Pivi. Tulkus 1880 to 2018" exhibit, 2012-2013.

https://www.castellodirivoli.org/en/mostra/paola-pivi-tulkus-1880-to-2018/

Description: "The 10th Panchen Lama Lobsang Thinley Lhundrub Choekyi Gyaltsen (1938-1989), photo circa 1948". Reuploaded to Pinterest. Original source and colorizer unknown.

https://i.pinimg.com/736x/e7/a1/ca/e7a1ca83922f6e6ce8fbf1857510bb1e.jpg

Pabongkhapa Déchen Nyingpo (1878-1941), a lama of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. Image posted on the website TsemRinpoche and reuploaded to Pinterest.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/367184175878678123/

The Third Trijang, Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso (1901-1981). A follower of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism and tutor of the 14th Dalai Lama. Image posted on the website TsemRinpoche and reuploaded to Pinterest.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/great-masters--461619030556734949/

1938-1939 National Socialist Tibet Expedition

In 1938-1939 National Socialist Germany conducted an expedition to Tibet. The dual purpose was to pursue closer diplomatic and military ties, as well as to conduct scientific and cultural studies to better understand Tibet's history. At the time, Tibet was considered to be a possible origin of the swastika and hence of the Aryan race.

This is one of many examples demonstrating how the National Socialist idea of the "Aryan race" was not synonymous with "whiteness" or "Nordicness".

Members of the German Tibetexpedition meeting with Tibetan dignitaries, 1938, Lhasa, Tibet, China. Photo in the collections of the German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv), Bild 135-KA-10-072.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_135-KA-10-072,_Tibetexpedition,_Empfang_f%C3%BCr_W%C3%BCrdentr%C3%A4ger.jpg

Description: "Gyantse, tibetische Maler beim Bemalen von Tibettischen, Malerutensilien (Sammlgegenstände)." "Gyantse, Tibetan painter painting Tibetan tables, painting utensils (collectibles)." Photo taken by the German Tibetexpedition, 1938. Photo in the collections of the German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv), Bild 135-BB-204-04.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_135-BB-204-04,_Tibetexpedition,_Kunsthandwerk,_Malerei.jpg

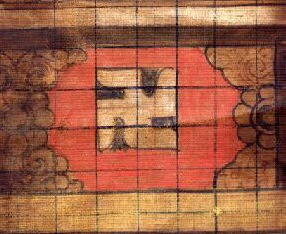

Relief showing 4 swastikas. Photo taken by the German Tibetexpedition, 1938, Lhasa, Tibet, China. Photo in the collections of the German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv), Bild 135-S-13-08-26.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_135-S-13-08-26,_Tibetexpedition,_Swastikarelief.jpg

Other and general examples in Tibet

"Although the swastikas and surrounding pictographs may have been made by different individuals, they form a thematically interrelated array. The mantra A’ Om hum was used regularly by non-Buddhists in Upper Tibet, as the epigraphic record indicates, in contrast to the Buddhist mantra Om A hum. Like swastikas that face in opposite directions, these alternative mantras highlight the interplay between religious exclusivity and religious borrowing.

It is likely that these symbols of a non-Buddhist group relate to religious traditions known as Dzokchen (Rdzogs chen), a philosophical and mind training school spanning the divides between Buddhism and bon and bon and Yungdrung Bon."[31]

***

Wilson (1898)[33] briefly described a few uses of the swastika in Tibet. He quotes William Woodville Rockhill Count Goblet d'Alviella.

In the late 1800s William Woodville Rockhill travelled through Tibet and made several observations of swastikas.

"Towards noon I went over to Kumbum to see the fair, and try to pick up some curios. I found there quite a number of Lh'asa Tibetans (they call them Gopa here) [...]

I had a talk with these traders, several of whom I had met here before in [18]89. They were very friendly and jolly. One of them had a swastika (yung-drung1) tatooed on his hand, and I learnt from this man that this was not an uncommon mode of ornamentation in his country. He said that he often sees at Lh'asa devotees (Atsara from India) with the three mystic syllables Om, A, Hūm, tattooed on their persons—the first on the crown of the head, the second on the forehead, the third on the sternum.

1. A hooked cross. It is a sacred symbol among the Buddhists and the Bönbo."[34]

Kumbum Monastery is located near Lusar, Huangzhong County, Qinghai Province, China.

*

"Tattooing as a means of ornamentation is hardly ever practiced by Tibetans. I have seen a few men from Lh'asa, or the adjacent countries, who had a "hooked cross" (yung-drung) tattooed on the back of their hands near the thumb, and some others with a round dot or two tattooed at the same place, but beyond this I have neither read nor heard of any tattooing among this people."[35]

*

"Like most Asiatics the Tibetans never sign their letters but seal them, nearly every one, even those who can not write, carrying a small seal (titsé) suspended from his girdle. These seals have on them a letter or a religious symbol surrounded by an ornamental design. They are cut in iron and are frequently of very delicate workmanship. In pl. 29, fig. 4, is shown a seal made in Dérgé; it is cylindrical, 2 and 1/8 inches long, terminates in a knob head, and is bored out, chased, and fretted. The design is a swastika or "hooked cross" in the center of a foliated motive."[36]

This seal is in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, catalog number E131317-0. There is no photo, but you can search for its record below:

https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/anth/

Derge is located in Dêgê County, Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China.

***

Swastikas on fabrics worn by a yak at Yamdrok Lake.

Photo by Wikipedia user Dennis Jarvis, 2006.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bos_grunniens_at_Yundrok_Yumtso_Lake.jpg

See other photos:

Photo by Wikipedia user Dennis Jarvis, 2006.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yak_in_Tibet-2.jpg

https://www.flickr.com/photos/archer10/8285206775/

Photo by Wikipedia user Dennis Jarvis, 2006.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Yak_in_Tibet-1.jpg

https://www.flickr.com/photos/archer10/2661318228/

Swastikas on fabrics worn by a yak at Khampa La Pass, near Yamdrok Lake. Photo by Wikipedia user Bgabel, 2010.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TIB-khampa-la-yak.jpg

Swastikas in Japan

In Japanese, the swastika is called manji.

Buddhism arrived in Japan by the 500s AD. The swastika was likely introduced during this time, if it had not already arrived.

Today, the swastika remains a standard symbol of Buddhism in Japan, and is frequently seen on maps depicting Buddhist temples. The swastika is sometimes found at Shinto religion shrines as well.

Historically, forms of the swastika were often used in various clan emblems, called mon or kamon (紋). As a legacy, some Japanese cities use the swastika as their emblem today.

Throughout Japanese history, the swastika is also seen as an ornament in clothing an architecture, including in the form of the 紗綾形 / さやがた (sayagata) fret design, on the robes of theater performers, and various other examples. Manji even became a popular youth slang in the 2010s, showing the symbol remains popular in Japan despite the biases of Westerners.

As a Buddhist symbol

Swastika at Sensō-ji temple, Asakusa, Tokyo, Japan. It was founded in the 600s and is the oldest temple in Tokyo. Photo by Wikipedia user Herbye, 2003.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Swastika.jpg

Lantern with swastikas in Sensō-ji temple, Tokyo, Japan. Photo by Flickr user cesar_camilla, 2012.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lanterna_do_templo_Sensoji_(6961815856).jpg

Swastikas under the roof of Sensō-ji temple, Tokyo, Japan. Photo by Wikipedia user Hyppolyte de Saint-Rambert, 2019.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sensoji_deux_toits_en_deux_plans.jpg

Swastikas on the roof of Sensō-ji temple, Tokyo, Japan. Photo by Wikipedia user Hyppolyte de Saint-Rambert, 2019.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_Sensoji_tuile_d%C3%A9corative_onigawara.jpg

Lanterns with left-facing and right-facing swastikas at Suma-dera temple, Kobe, Japan. Photo by Malcolm Fairman, 2009.

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-array-of-paper-lanterns-chochin-hanging-all-with-black-kanji-inscriptions-82741807.html

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-array-of-paper-lanterns-chochin-hanging-all-with-black-kanji-inscriptions-82741812.html

Small Buddhist shrine at Naruko-Zaka, Shinjuku, Tokyo. Photo by Wikipedia user ウィキ太郎(Wiki Taro), 2021.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_small_shrine_of_Jiz%C5%8D_or_K%E1%B9%A3itigarbha_at_Shinjuku_%E6%96%B0%E5%AE%BF_%E6%88%90%E5%AD%90%E5%AD%90%E8%82%B2%E5%9C%B0%E8%94%B5%E5%B0%8A.jpg

Swastika at an unspecified Buddhist temple in Japan. Photo by Flickr user mark_boucher, 2003.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/mark_boucher/22037794/in/photostream/

Swastika under the peak of the roof and on banners at Zenkō-ji temple, Nagano, Japan. The temple was established in the 600s. Photo by Wikipedia user 663highland, 2015. (Click link below to zoom in to the full size image).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:160501_Zenkoji_Nagano_Japan06s3.jpg

Road sign with swastikas indicating Buddhist temples. Kamakura, Japan. Photo by Wikipedia user Wicki, 2009.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Buddhist_temples_in_Kamakura.JPG

***

Wilson (1898)[37] cites an example of a bronze Buddha statue with right-facing swastikas, from the collection of Henri Cernuschi, which is presumably now in the collection of the Musée Cernuschi.

***

If you want to dive in and try to catalog every potential Buddhist swastika in Japan, you can start here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Buddhist_temples_in_Japan

As a symbol in Shinto

Shinto is considered an indigenous religion of Japan, and has been influenced by Buddhism and other teachings over its history.

Swastikas on lanterns and banners in the Chingodo Shrine, Denboin Street, Asakusa district, Taitō special ward, Tokyo. Photo by Wikipedia user すけ, 2009.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Templo_(altar)_en_Asakusa_(Jap%C3%B3n).JPG

Also see:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chingodo_Lanterns.JPG

Description: "Swastikas on Shinto Shrine, Osaka, Japan." Image posted on the blog Sydney In Osaka in 2017.[38]

Description: "Shinto Shrine with swastika near Nishikujo Station in Osaka, Japan." Image posted on the blog Sydney In Osaka in 2017.[38]

Description: "Shinto Shrine with swastika near Nishikujo Station in Osaka, Japan" Image posted on the blog Sydney In Osaka in 2017.[38]

Description: "Shinto Shrine with swastikas in Kyoto, Japan." Image posted on the blog Sydney In Osaka in 2017.[38]

As a personal, clan, and location emblem

Mon or kamon (紋) refers to a type of emblem for a clan or individual. Many clans throughout Japanese history used different types of swastikas.

***

The Hachisuka clan formed in the 1300s AD. They ruled land in what is now Tokushima Prefecture.

Idealized emblem for the swastika-in-a-circle emblem used by the Hachisuka clan.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Japanese_Crest_Maru_ni_Hidari_Mannji.svg

Description: "Arrow Bracket with the family crest of the Hachisuka clan - a swastika Japan Edo period". 1600-1868 AD. Photo by Wikipedia user Шнапс, 2009. Museum collection unknown.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:%D0%A1%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%B0_%D0%B4%D0%BB%D1%8F_%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BB.JPG

Original caption:

Е127

Скоба для стрел

с фамильным гербом клана Хатисука - свастикой

Япония

периодЭдо

Statue of Hachisuka Iemasa, showing the swastika emblem. Tokushima, Japan. Photo by Wikipedia user Fg2, 2006.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tokushima_Hachisuka_Iemasa_M3753.jpg

Below, the banner on the left was used by Hachisuka Iemasa (1559-1638).

_Banner.jpg)

Anonymous. (c. 1800s). "Hataumajirushi ezu". In the collection of the Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

https://archive.org/details/hataumajirushiez02/page/n27/mode/2up

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Uesugi_Kagekatsu_Battle_Standard_and_Hachisuka_Iemasa_(1559-1638)_Banner.jpg

***

Hasekura Tsunenaga (1571-1622) was a samurai who converted to Christianity in 1615 after serving several years as a diplomat to Spain and the Pope. He used a Western-style heraldry coat of arms with a swastika.

Depictions of Hasekura Tsunenaga's coat of arms in historic illustrations. Description: "Left image: from Hasekura's Act of Roman Citizenship. Middle image: from the German edition of Hasekura's travels to Europe. Right image: Flag of Hasekura's ship, personal photograph from Sendai Museum, released in the Public Domain."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:HasekuraBlason.jpg

Idealized version of Hasekura Tsunenaga's banner. Uploaded to Wikipedia by user "Di (they-them)".

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hasekura_Tsunenaga_banner.svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hasekura_Tsunenaga_coat_of_arms.svg

***

The city of Hirosaki in Aomori Prefecture uses a red swastika on its flag. It is said it was used as an emblem of Tsugaru clan, rulers of the city during the Edo era.

Japanese-language Wikipedia lists a swastika as the family crest of the Tsugaru clan,[39] although that does not seem to be their main or most recent emblem, given that a different one is shown on their main Wikipedia page.

Flag of Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, Japan.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Hirosaki,_Aomori.svg

Large swastika during a parade in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, Japan. Photo by Flickr user forecastle, 2014.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/forecastle/14966804985/

***

The town of Numata, Hokkaido, also has a swastika emblem.

Flag of Numata, Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Numata,_Hokkaido.svg

Emblem of Numata, Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emblem_of_Numata,_Hokkaido.svg

***

As of writing this article, the Japanese-language Wikipedia page for family crests shows 4 with swastikas.[39]

A translation says that a left-facing swastika in a circle is used as:

"丸に卍(万字):阿波薬王寺紋、讃岐観音寺紋"

"Swastika in a circle (manji): Awa Yakuoji crest, Sanuki Kannonji crest"

That is Yakuo temple in Minami, Kaifu District, Tokushima Prefecture, and Kannonji temple in Kan'onji, Kagawa Prefecture.

The page links on Japanese-language Wikipedia show that the swastika-in-a-circle mon was also used by the Yokoyama clan.[40]

A rotated swastika elongated into a diamond is shown on the Japanese-language page for family crests,[39] but the specific clans which used it are not specified.[39][41]

There is another example of a diamond swastika, but it too does not appear to have any specific clans listed.[39][42]

***

The Japanese-language Wikipedia article for Shōryūji Castle shows a right-facing swastika as an emblem for Hachiya Yoritaka,[43][44] a defender of the castle in the battle of 1568.

***

Wikipedia claims the following,[45] although it does not specify page numbers for its reference to 60 clans of the Tokugawa clan using the swastika. The Tsugaru and Hachisuka clans are examined above.

"Since the Middle Ages, it has been used as a mon by various Japanese families such as Tsugaru clan, Hachisuka clan or around 60 clans that belong to Tokugawa clan."[46]

***

The Japanese-language Wikipedia page for vassals of the Satsuma clan (which existed from 1602 to 1871) shows a few which used swastikas for emblems.[47] I have not been able to find much more information on these families or clans.

***

The following illustrations appear to be from a book titled 「我が家の家紋」 ("Our Family Crest"), which has 3720 examples of mon grouped by motif type. I can't find much more information about this book. The images are posted on the website for Morisige Corporation,[48] which appears to be an online marketplace selling various items. There is a copyright notice from 2003 in the page's source code, so presumably the book is from that date or prior.